Some reflections on geoeconomic fragmentation - Speech at the Dublin Chamber by Governor Makhlouf

30 April 2025

Speech

Good evening1,and many thanks to Dublin Chamber for the invitation to join you.

This evening I am going to reflect on recent global developments, what it may mean for the economic outlook, and in turn how economic policy in Ireland and Europe more generally should evolve.

Much of what we are seeing now is a particularly swift realisation of one of a number of transitions the economy is facing, with various implications across the near, medium and longer-term. Understanding the drivers of these transitions, and the nature of their implications, provides clear motivation for policy to maintain and build economic resilience, so that households, businesses and the community as a whole can weather the inevitable storms, and take the opportunities that such transitions can also provide.

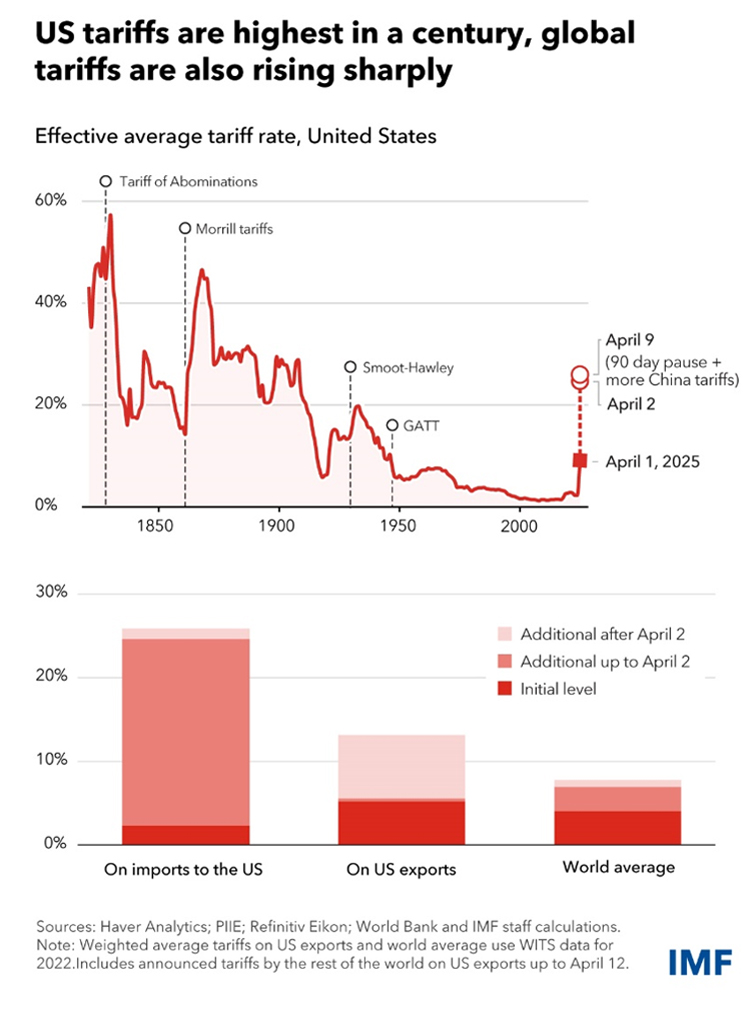

I have reflected before on a number of these transitions, such as demographic change, climate change and digitalisation, but this evening I will concentrate on shifting geoeconomic relationships and possible fragmentation.2 This is an issue at the forefront of our minds given the scale of change being brought about by the US Administration, the high volume of announcements and policy changes, including imposing, removing and pausing of widespread tariff and non-tariff barriers, and the retaliatory responses across major economies. Effective average tariff rates have risen, most notably in the US, reaching levels not seen there in almost a century (Chart 1).

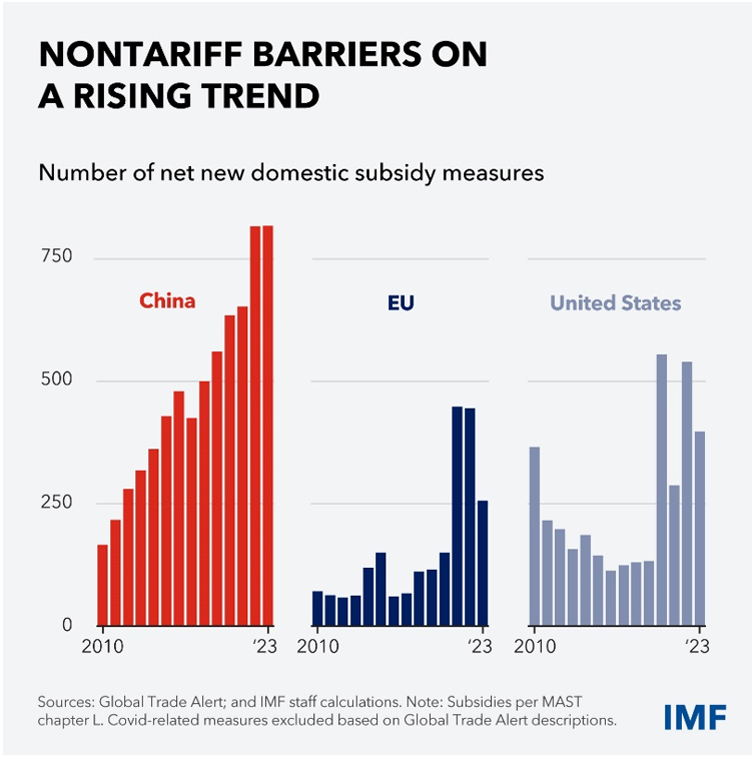

Non-tariff barriers have also risen in recent years (Chart 2).The ebbs and flows of cross-border trade and investment can always lead, and be led by, diverse political reactions and positions across countries. However, over the last few months we have witnessed a relatively rapid increase in policy uncertainty and a challenge from the US Administration to the multilateral institutional framework that has underpinned global economic relationships for much of the last 80 years.

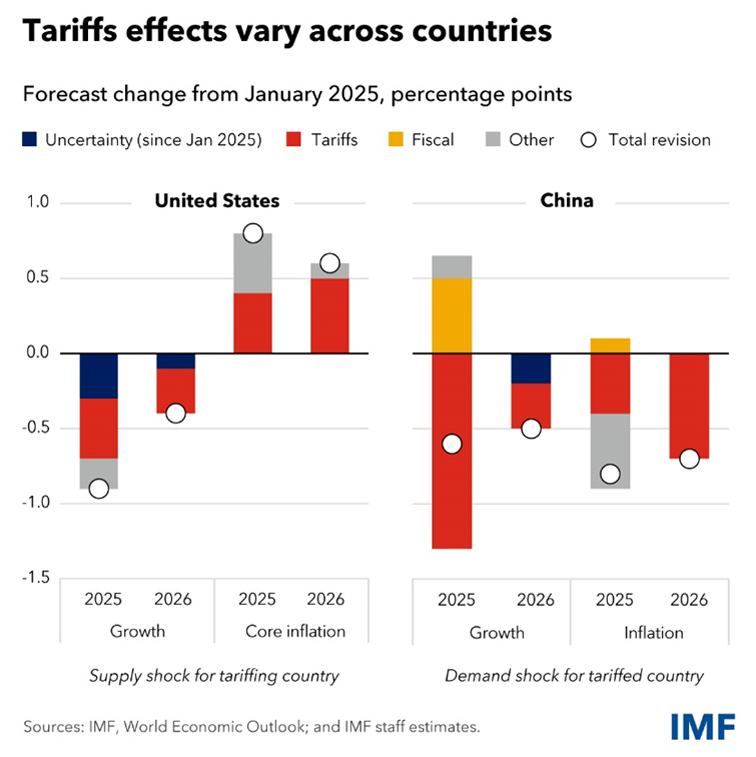

The analysis and outlook3 published by the IMF last week were clear, with four key messages. First, the imposition of tariffs and other trade barriers as announced will be a significant drag on the growth outlook globally, and especially so in the United States and China (Chart 2). Second, policy uncertainty is also weighing on the growth outlook, damping consumer spending and business investment. Third, downside risks to growth have risen and the possibility of a more significant slowdown cannot be ignored, with the prospect of worsening trade tensions, tighter financial conditions amid higher public and private debt levels, and complex interconnections within the financial system which could amplify negative shocks. And, finally, prospects could rapidly improve if countries adopted a more cooperative approach to addressing the issues underpinning their trading relationships.

In trying to chart a course forward, it is useful to reflect on the possible motivations for those currently driving trade tensions higher. What costs have economies and societies borne with the opening up of trade and investment flows across the globe? What will countries be forsaking if there is a continuation to a more closed and protectionist approach? And, is there an opportunity to build on the benefits of openness while addressing any costs that may arise?

As economists, the benefits of trade are close to being hard-wired into us, drawing as they do on the writings of David Hume and the basic principle of comparative advantage first put forward by David Ricardo over two centuries ago.4 Obviously our understanding has evolved since then, alongside the realities and complexities of modern industrial production, global value chains and multi-national enterprises, the growth of services trade, and advances in technology and connectivity. However, the basic principle that motivates economies and businesses across the world still holds: produce specific goods and services where it can be done more efficiently or with lower costs, and then trade to get access to other goods and services produced elsewhere on the same basis. Ricardo’s insight was that allowing such trade without impediments allows for both countries to consume more of every good, and as a result generate more income than in the case where trade does not take place or is impeded by things like tariff or non-tariff barriers.

This basic principle of the benefits of trade openness has, to varying degrees, underpinned much of the international economic policy agenda since the end of World War II. While empirical studies can find different extents of the relationship depending on the starting point, time period considered and institutional factors5, increasing trade openness has been found generally to be associated with higher growth in GDP per capita, a marginally lower level of income inequality between countries, and a reduction in absolute poverty especially in emerging and middle-income countries, most notably in Asia. As we know from our own experience in Ireland, openness to international trade has been one pillar of our economic policy since the late 1950s and has contributed significantly to economic development here. We also understand what the impact of an economy closed to international trade can be.

So reverting to a world with more barriers to trade, added to by the inevitable tit-for-tat response in tariffs, poses significant challenges. Trade wars more often than not lead to lose-lose situations, and often as the negative implications escalate the more intense the conflict. That’s clearly seen in the IMF analysis published last week, whereby the hit to growth prospects arising from the higher tariffs is more significant for the US and China. Higher tariffs are regularly shown to have negative consequences for productivity and long-run growth prospects for economies that implement them. Higher tariffs are also regressive in nature up-front, with poorer households bearing a relatively higher burden of price increases (with the US experience of the 2018 increase in tariffs being among the most recent evidence of this.)6 Retaliatory responses to unilateral actions are understandable. However, we in Europe need to articulate a clear perspective on the benefits being foregone when trading partners adopt more protectionist stances. We also need to work with trading partners to inform a clear approach to address the underlying drivers that motivate those protectionist stances. And, we need to invest more in working with new trading partners who also believe in the benefits of barrier-free trade.

A macro perspective

From a macro perspective, the US Administration is, apparently, focusing on reducing or eliminating persistent US trade deficits, or more specifically US goods trade deficits. However, the corollary of a trade deficit is an excess of domestic demand over domestic saving, which in the US case is also evident in the persistent budget deficit, which has grown to about 6.5 per cent of US GDP. On the other side of the equation, large trade surpluses, such as those in China, are mirrored by an excess of domestic saving over domestic demand – and broadly speaking that excess saving has found its way into US Dollar assets, including US Treasuries issued to fund the US budget deficit. Higher tariff and non-tariff barriers won’t necessarily address these imbalances, and if they do it will be at a substantial cost to productivity growth and long term sustainable growth for the countries affected. A more sustainable approach would instead see a rebalancing of domestic saving and domestic demand in major economies, through sustainable fiscal consolidation in deficit countries and enabling more private domestic demand elsewhere.

These macro identities and patterns point to an area for further discussions between trading partners that could resolve some of the current pressures and result in better outcomes for all. But it is also necessary to dig beneath a bit more to understand better some of the key drivers of protectionism. From that more micro perspective, there are two issues that warrant consideration. First, the different income, wealth and opportunity experiences within countries that have coincided with greater openness to trade and investment. Second, the strategic objective of maintaining supply chain security for critical goods and services.

On the first, while greater trade and financial openness are generally associated with higher GDP per capita in a country, it does not, in and of itself, mean that those gains are felt within a country to the same extent.7 In many economies, Ireland being among some notable exceptions, measures of post-tax income and wealth inequality have typically increased in recent decades alongside greater openness. In addition, evidence in a number of countries points to a related increasing perception of economic unfairness, low social mobility and increased economic insecurity. To paraphrase, a rising tide lifts all boats, but not all boats are equally able to withstand the swells of stormy weather. Or, in other words, economic transitions need to be managed to help navigate the storm and enter into calmer waters.

It is difficult to pinpoint the precise role of trade openness, financial openness, and technological advancement in these within-country trends, as the three are inter-related. Unlike Ricardo’s simplified example two centuries ago, capital, labour and ideas are potentially mobile, and how they interact with the geography of trade will influence people’s experience of the gains from trade openness. It will likely also influence their subsequent responses to trade openness, or levels of trust in institutions, an important element of the social capital needed for economies to thrive.8 However the evidence also points to the ability of policies and institutional frameworks that help to manage economic transitions and can promote broader gains to openness within countries, most notably through education and access to technology. Indeed, higher levels of educational attainment is likely one reason why Ireland is among those countries who have seen broader gains from openness.9

On supply chain security, the disruption arising from the pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine brought to the fore the need to build resilience in our economies to withstand shocks to the flow of critical goods and services. I have also reflected how the evolution of payment systems10 present another area where concerted effort is required to reap the benefits of technological advances while preserving strategic autonomy. Similar to seeing the economic gains from openness being more widespread, this points to the need for effective policies and institutional frameworks that can complement achieving wider societal goals. Two examples that come immediately to mind are those frameworks which can facilitate more use of renewable energy domestically with less reliance on fossil fuels, and the adoption of the digital euro and a wholesale Central Bank Digital Currency as a European owned universal digital payment system.

With the exceptional uncertainty around where things might finally land, it is difficult to say what the impact of US tariffs, and any retaliation by the EU and others, is likely to have on inflation in the Euro area. It will be influenced by a number of factors, including trade diversion, especially China-EU trade flows, and the exchange rate. The dollar depreciation since early April suggests lower risk appetite for dollar assets, outweighing the lower import demand effects that would have led to an appreciation. The relative appreciation of the euro is deflationary, especially for imports of energy and other commodities which are priced in dollars. The growth outlook, both globally and for the euro area, has deteriorated (as we saw in the IMF forecasts). Increased uncertainty is weighing on consumer and business confidence. Business investment in particular is likely to be stalled until the tariff backdrop is settled, one way or another.

Furthermore, the market response to recent events has led to a tightening of financing conditions. All of these factors are a negative for the economic outlook for the euro area, and a downside risk for inflation in the near term. However, for the more policy-relevant medium term outlook, the risks are less clear. All of this uncertainty reinforces the value of following a meeting-by-meeting approach to determining the appropriate monetary policy stance for the euro area.

What will the impact on Ireland be?

When we look at Ireland specifically, the economic vulnerability here to a more fragmented trade and investment dynamic between the EU and the US is considerable. Multinational enterprises (MNEs) in Ireland, many of which are US-owned, are integrated into global value chains in major sectors like pharmaceuticals, med-tech, and ICT manufacturing and services. A number of our most prominent indigenous exporters in agri-food and small cap manufacturing also have significant exposure to the US market. However, the vast majority of Irish exports, along with the associated profits, tax revenues, and employment generated from this sector, are intrinsically tied to both US investment and the inflow of US services.

In fact, Ireland experiences an overall trade deficit with the US, as the deficit in services trade surpasses the surplus in goods trade. Approximately 50 per cent of the value of Irish exports comes from foreign-sourced inputs, with the US being the primary provider of those inputs, especially in the largest economic sectors. For instance, nearly 15 per cent of the total value of Ireland's pharmaceutical exports ultimately stems from inputs imported from the US. At the same time, almost 20 per cent of the value of Irish exports ultimately go to the US, although the EU continues to be the largest single source of final demand for Irish exports.

Depending on the specifics, the application of tariffs and non-tariff barriers could significantly impact the operations of MNEs in Ireland over the longer-term, particularly if they affect their relative profitability. The most immediate reflection of this may be in the public finances, given the large share of corporation tax receipts arising from US MNEs, with corporation tax now accounting for over a quarter of all tax revenue. This likelihood increases further if trade-related barriers coincide with broader changes in tax and industrial policy that could discourage investment and activity in Ireland. Such situations pose a major downside risk to the economic outlook. Even without specific details or the actual implementation of policies, the current rapidly changing policy environment is significantly elevating uncertainty, and this uncertainty is already weighing on business investment here.

What does this mean for Irish economic policy? Earlier this year I wrote to the Minister for Finance (PDF 2.83MB) outlining what I think are the key priorities given the current backdrop, acknowledging the need to address issues with a long-term perspective.

These priorities still hold:

- Prioritise capital expenditure and tax base broadening to create the economic and fiscal space for the necessary increase in investment needed in housing and public infrastructure the coming years;

- Enhance and introduce structural reforms to reduce the costs of infrastructure delivery and boost productivity in the construction sector;

- Further enable the expansion of the labour force including through increased labour force participation and productivity, supporting life-long learning and adaptation to technological change;

- Continue to support efforts to mitigate geoeconomic fragmentation while protecting supply chain security.

Achieving decisive progress across these policy priorities would boost productivity here in Ireland.

What opportunities might arise?

It is safe to assume that the world of international trade that we have been familiar with since the end of World War II will change over the short to medium term and we (both here in Ireland and in Europe) should begin to plan, and act, on that basis. In my view, policymakers should use this transition to look for opportunities and ensure that the economic impact of any tariff measures are lessened. I do believe that there is opportunity for both Ireland and the EU in this transition.

Across Europe, we need to examine where we can remove supply constraints, and consider where redirected demand can be used to stimulate domestic markets.11 For too long Europe has maintained high internal barriers, which have acted as an anchor to trade, and by extension growth. Both Mario Draghi’s and Enrico Letta’s report last year set out what could be done. Policies that seek to boost productivity and innovation should be pursued along with the completion of the EU Single Market, including the delivery of a single banking union, and the Savings and Investment Union. We want capital to be allocated more efficiently throughout the European Union, harnessing the power of our Single Market while remaining open to global capital and aligned to global standards. To repeat, we need to focus on removing the remaining internal barriers to trade in goods and services. A deeper and stronger Single Market will, in turn, boost the returns to investment.

From a broader perspective, sustainably mobilising private savings across the EU for investment in Europe’s productive capital stock would create a more vibrant funding environment for infrastructure and innovation. The Savings and Investment Union must deliver if Europe is to regain its competitive edge, and if we are to find ways to unlock the €11.5 trillion held by Europeans in deposits and cash and channel it to drive European innovation.

And, finally, the majority of the world continues to believe in a multilateral rules-based trading system. We need to be ready to work with new trading partners that think similarly to us.

Conclusion

Let me conclude. We are certainly living in interesting and challenging times. But, with the right choices, we have the opportunity to build resilience in the economy and public finances to withstand a more fragmented geoeconomic environment. We can do this by focussing on what we can control to make Ireland an attractive place to live and do business. And, at the same time, we can continue to engage and influence our partners in Europe and beyond about the benefits of openness, multilateralism and institutional frameworks that promote win-win outcomes for all.

Chart 1: US tariffs are highest

in a century

Chart 2: Non tariff barriers

Chart 3: Tariff effects vary

across countries

[1] Thank you to Vasileios Madouros, Conor O’Shea, Rob Kelly, Rea Lydon and Martin O’Brien for their help in preparing these remarks.

[2] See, for example, Building Economic Resilience (speech at IIEA February 2025), and The Tangle of Ageing Populations and Productivity Growth (speech at Society of Professional Economists, November 2024).

[3] See the flagship IMF reports published during the Spring Meetings – the World Economic Outlook, the Global Financial Stability Report and the Fiscal Monitor.

[4] Ricardo, David. (1817) On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation. In Ricardo’s seminal example, he outlined a hypothetical two-country (England and Portugal), two-product (cloth and wine) world with immobile capital and labour. In this simplistic setting he showed that if each country focussed on producing just the product which they were most efficient in (cloth for England and wine for Portugal) and traded with the other country for the other product, then both countries would be able to produce and consume more of both products. This holds even when one country has an absolute advantage of being more efficient in producing both products (as Portugal was assumed as having in Ricardo’s example).

[5] Heimberger (2021).

[6] Furceri et al (2018) and Carrol & Hur (2022) provide evidence of the macroeconomic and distributional effects of higher tariffs. Looking back further, Irwin and Chepeliev (2021) find a reduction in income inequality arising from the repeal of Britain’s Corn Laws and the related reduction in tariffs on grain imports in 1846.

[7] Some interesting references in this respect include Pavcnik (2011), Nolan (2017), Rodrik (2018), Heimberger (2020), Protzer (2021), Quereshi (2023).

[8] Rebuilding social capital: The role of Central Banks – Gabriel Makhlouf 2022

[9] Ireland has among the highest levels of educational attainment across all age categories in the EU. Tertiary educational attainment among the population aged 25-34 reached 63 per cent in 2023.

[10] Governors Blog - Digital Dividends: Unlocking innovation in the payments ecosystem

[11] European Commission's new Competitiveness Compass examines a path to achieve this.

* Vasileios Madouros speaking on behalf of Governor Gabriel Makhlouf