Banking – Past, Present and Future – Remarks by Deputy Governor Sharon Donnery at the Banking and Payments Federation Ireland

31 July 2024

Speech

As the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) of the European Central Bank (ECB) celebrates ten years of centrally supervising European Banks, reflections on the retail banking system in Ireland, progress made and threats and opportunities ahead.

Good afternoon, I am delighted to be here. Many thanks to Brian and the BPFI for hosting me, and I look forward to the discussion.[1]

In my remarks today I wanted to outline some thoughts on the banking sector in Ireland and Europe – in the context of a rapidly changing and digitising world, and indeed financial system.

As the ECB celebrates ten years of the SSM and centralised supervision of the largest banks in Europe, I want to look back at how we have dealt with the challenges of the past – before looking forward to how we must prepare for the challenges of the future.

First comes first though – why do Banks, and indeed the health of Banks, matter?

A well-functioning financial system is vital for consumers, businesses and the economy.

In Ireland and Europe banks are a key part of that financial system. By allocating credit, safeguarding people’s money and facilitating their transactions the sector performs an important function for our society.

When it goes right, banks contribute to economic growth – increasing living standards – and bring benefits to individuals and the country.

But we have also all seen what happens when it goes wrong – when credit allocation becomes a bubble, or a crunch, when people fear for the safety of their money, or when systems fail and transactions don’t transact.

Clearly, a well-functioning financial system relies on well-functioning banks. And this is why the health of the banking sector is so important – so that it can sustainably perform its function for society, through good times and bad.

Where we have come from

Ensuring the resilience of the banking system has been a key focus for most of my career.

While suffice to say there have been ups and downs, more than 15 years on from the financial crisis, and almost 10 years after the establishment of the SSM, it is fair to say we have come a long way in the Irish and European banking sector.

The regulatory framework has been significantly enhanced; balance sheets have been cleaned up – and fortified; resilience has been strengthened – and indeed tested; and the financial sector has transformed around us.

For Ireland, the journey travelled in terms of the health of the Irish banking system has been remarkable – and is well illustrated by two key metrics which the country, and indeed Europe, has spent much of the last decade and a half focused on.

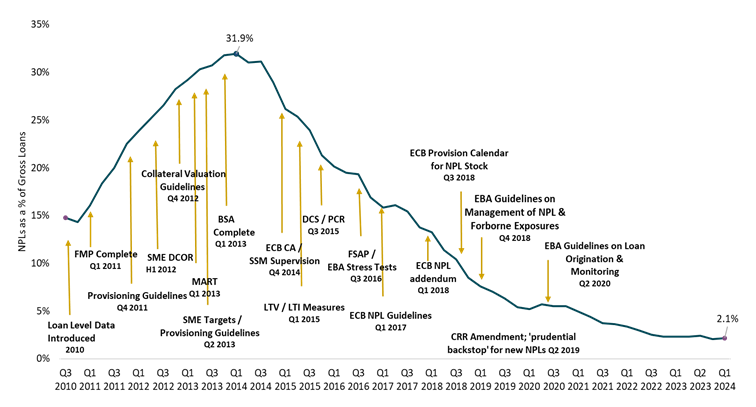

The first is Non Performing Loans (NPLs) – which at high levels over a sustained period of time can undermine the resilience of banks, and restrict the role they play in providing credit to households and the wider economy.

Post financial crisis the Irish banking sector was weighed down by an extraordinary level of NPLs. 10 years ago, the NPL ratio of Irish banks peaked at just under 32%.[2] Today, the ratio stands at just over 2%, with much of the reduction coming between 2014 – 2019 – driven by effective and intrusive supervision, intensive workouts and restructuring by banks themselves, and an improving economy.

Credit Risk – Credit Quality Overview

Source: Central Bank of Ireland regulatory returns.

Note: At Q3 2014 the EBA’s definition of non-performing was introduced. Prior to this date an internal definition was used equivalent to impaired loans and/or arrears > 90 days.

Following the advancements in the loan portfolio sales for the existing Irish banks in 2022, the format of their regulatory reporting has changed considerably which has affected reported Loan/NPL figures on an aggregated basis in between Q3 2021 and Q2 2023.

The other metric is of course capital adequacy. Capital is crucial for the health of banks and the system: allowing them to absorb losses, and ensuring they are sufficiently resilient to serve the needs of the economy through the cycle.

Following the Great Financial Crisis, European policy priorities were to improve the quality and quantity of bank capital – and this was very much the priority in an Irish context too.

Thankfully over the last 10 years strong capital buffers have been collectively built in the system – with an additional €23bn worth of loss absorbing capacity within the three Irish pillar banks, and their collective Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratios rising from 11.9% in 2014 to 15% in 2024.[3]

Recognising the critical role liquidity plays in absorbing initial shocks, alongside enhancing the loss absorbing capacity of the system, there was a fundamental overhaul of the liquidity framework for banks – ensuring they now hold higher levels of high quality liquid assets to meet outflows in stress environments.

In addition to these key post crisis resilience measures, also came a decade of deleveraging and more prudent lending standards in the banking sector – leaving our citizens, our economy and our financial system much less exposed.

This included of course more robust underwriting by banks themselves; but it also importantly included our macroprudential mortgage measures – which have made a significant contribution towards maintaining the resilience of borrowers, lenders and the broader economy over the last 9 years. Thanks to these measures, only about 6% of mortgages are now written at loan to income ratios above 4 – compared to around half of new mortgage lending in the run up to the financial crisis.[4]

Learning the lesson

Thanks to all of this work, by regulators, policymakers and banks themselves, we have a much more resilient sector and households, with better run and better supervised institutions.

Looking back, I know we can all agree that these actions – to reduce NPLs, to build financial resilience and to introduce macro-prudential measures to maintain this resilience – were not just necessary, but were in fact crucial.

For when one thinks of recent challenges and shocks – Brexit, Covid, Russia’s unjust invasion of Ukraine, and the rapid tightening of monetary policy – the counterfactual of entering these episodes with weakened balance sheets, limited capital buffers and unsustainable lending practices would have brought considerable strain to the system – and society – once more.

Now some might say all this is history; but to paraphrase the philosopher George Santanya – “those who cannot remember their history are condemned to repeat it.”[5]

And indeed, at this stage of the regulatory cycle, I sometimes fear memories are starting to fade a little – in particular in light of the recent shift back towards industrial policy and competiveness. Competitiveness is of course important – but as I have said before, a robust financial sector, through the cycle, is ultimately a more competitive one; and chasing short term growth through de-regulation rarely pays off in the long run.

The market volatility both sides of the Atlantic last year served as a reminder of this. While we can never be complacent, the resilience of Irish and EU banks during that period should be seen as clear vindication of the collective work of the last decade – work which we must preserve.

Profitability and distributions

So, Irish and indeed European banks are in a much more robust position – they are better run, and better supervised; they are subject to higher standards of regulation and have much better capital and liquidity positions.

Profits have even returned to the sector – in part thanks to the changed interest rate environment – which facilitates continued balance sheet strengthening, allows for important re-investment in the business as well as the returning of value to investors.

While this all puts the banking sector in a strong position, when we think about the changing financial system, and the rapidly changing external context which we are all operating in, it is clear there are significant risks ahead.

But before I touch on those, I want to say a word on profitability – and distributions – for it is something I am often asked about.

To begin with, why do regulators care about profits?

Well a safe bank needs to be a profitable one over the long term. While there will be variations in profitability over the business cycle, banks need to ensure that they can cover their costs, build financial buffers through capital accretion for risks ahead, while also generating enough income to invest in its future – so that its systems are robust and it can meet the evolving demands of consumers.

As you all know, for the last 10 years regulators had concerns about low profitability in the banking sector and the sustainability of its business models. And while the changed interest rate environment has led to high profitability in recent years, it has not necessarily made bank business models any more sustainable. Nor can higher rates be relied on to indefinitely last into the future.

This brings me to distributions, an important part of the investability of banks – which plays its own role in the stability of the sector.

In Ireland and in Europe, regulators seek to be proportionate in limiting dividends during periods of stress. During the incredible uncertainty of the Covid-19 pandemic, the ECB requested banks not pay out dividends – to boost banks’ capital to absorb losses and support lending to households, small businesses and corporates.

In normal times, however, well-capitalised banks, appropriately provisioning, and adequately investing in their future will correctly look to make distributions to shareholders.

It is against these metrics which we judge distribution decisions– and once they are satisfied, it is up to the firms themselves to make choices and manage the expectations of their different stakeholders.

As to whether banks are well capitalised – given the levels we have gotten to in recent years this is generally the case.

In terms of appropriate provisioning, this is of course a more fluid situation – one that well run banks must always be managing and one that very much must be based on a realistic and prudent assessment of the risk outlook. In that regard, in uncertain environments such as we have today, good risk management requires a better use of provisioning overlays to consider the impact of novel risks more precisely.[6]

As to whether banks are adequately investing in their future – while recognising capacity constraints, I believe that this remains to be seen. For the sector has changed enormously in recent years, with potentially profound changes to come.

Changing financial system

Over the last decade, the Irish financial sector has changed significantly – becoming larger, more diverse, more international, and more complex.[7]

The sector is also becoming increasingly digital, even if the digitalisation of retail banking has lagged behind other aspects of our daily lives.

In that regard, since 2016 the total value of monthly card payments has nearly doubled from €4.6 billion to €9.3 billion.[8] In volume terms the growth is even more stark – with monthly card transactions tripling from c 70m to 222m transactions over this period. 86% of consumers report using mobile banking – with mobile apps now cited as the main form of contact with their providers.[9]

While it is natural for observers to notice when the system doesn’t work well, it would be remiss not to recognise how much goes right every day – including the millions of payments made, more than 80% of which are now contactless.[10]

But in a system based on trust, and with expectations of a seamless digital access from consumers in all parts of their lives, attention naturally focuses on when things don’t work well – highlighting the fundamental importance of delivering operational, as well as financial, resilience.

Now don’t get me wrong – in complex digital systems with multiple dependencies it is understandable that disruptions can occasionally occur. And indeed we only saw this month the fragility of the IT systems we so rely on, in particular given the concentrated nature of parts of the market – reinforcing why we are so focused on cyber risk, as well as digital operational resilience.[11]

However, disruptions should not happen due to a neglect in dealing with known issues within your own systems – or due to insufficient risk management of the outsourcing of critical functions. And when disruptions do happen, how you react – and in particular how you communicate with your customers – is key.

And if banks are to continue to perform their important function in a changing and increasingly digital society – they must change too. This requires you to transform your strategies, systems and digital infrastructure – to keep pace with the digitalisation of the sector, to ensure banks remain operationally resilient within this environment, and to meet increasing consumer demand and expectations for digital financial services.

While this has been true for a number of years, this transformation hasn’t always been delivered at levels required in a rapidly evolving and digitalising financial system. As the pace of this digitalisation accelerates, delivering this transformation is no longer a “nice to have” – but is quickly becoming a non-negotiable.

The future is inevitable

Digitalisation is not the only change and challenge the system is undergoing – structural challenges such as climate change and demographics strike at the heart of bank balance sheets; and the geopolitical instability of recent years poses important questions for a deeply global financial system.

On a sober assessment of the future, all of these challenges – digitalisation, climate change, demographics and geopolitics – may well be set to accelerate.

But while “the future is inevitable, it is not precise”[12] – with huge uncertainty as to how these structural transitions will unfold. What is clear, however, is their potential to introduce profound change to our lives, and your businesses.

In terms of Digitalisation – the development of Central Bank Digital Currencies and the expansion of Distributed Ledger Technology could have serious implications for a banking system not keeping pace with the digital demands of its customers. Likewise, if Generative Artificial Intelligence meets even a fraction of its promised potential it will have a transformative impact on society, the economy and the financial system.

In terms of Climate Change I have spoken before of the profound challenge it presents, including to banks considering bank balance sheets reflect the economy that they serve. [13] Like digitalisation, this is also an area where there is much more for the sector to do – with banks needing to improve their risk management now, to ensure their resilience for the future.

Demographics is another significant challenge facing Ireland and Europe. In Ireland the old age dependency ratio[14] is expected to increase from around 25% in 2022 to 47% in 2050; between now and then the population aged 80 and over in Ireland will increase dramatically – by more than 160%.[15]

This will have many implications for banks – ranging from the downward pressure older demographics may place on the natural rate of interest,[16] to the types of products your consumers will demand, with consequential effects for your assets and liabilities and potentially the stability of the sector.[17]

Finally, as we have all seen Geopolitical instability has led to – albeit so far gradual – geo-economic fragmentation in recent years. And geopolitical risks and their transmission have increasingly been a focus of supervisors.

While it remains to be seen whether this instability will intensify, further geo-economic fragmentation and a regionalisation of the global economy would of course have significant implications for the global financial system – including increased macro-financial volatility and instability, more costly and fragmented capital flows, not to mention the cyber and asset valuation risks that would be characteristic of a widening of global conflict.

Each of these structural changes on their own would test the banking sector, and its ability to continue to safely perform its important role in our economy. Combined they represent a fundamental challenge – one banks and their boards must start grappling with. For a future that may appear distance, has the potential to close in fast.

How the Central Bank of Ireland is responding to change

The changing financial system and structural challenges on the horizon effect us all – banks and Central Banks alike.

And as outlined in our Strategic Plan, the Central Bank of Ireland recognises that we too must change to keep pace with the changing world and continue to deliver on our mandate.

A key part of addressing this challenge has been transforming our approach to regulation and supervision – and I would like to finish by outlining some of the work we are doing in this regard.

Over the last two years we have introduced a significant step change in our external engagement – recognising that the rapid pace of change means that we need to be well-connected to our stakeholders.

This means listening to them, being more transparent, explaining ourselves better and increasing the clarity of our expectations.

In the face of feedback, we have also improved our approach to authorisations: increasing engagement and our responsiveness, and significantly improving our process (and we will continue to do so) – all the while maintaining the appropriately high standard the public expects for firms authorised to provide them with financial services. At the same time, we have enhanced our engagement with innovation in financial services; and we will deliver our first Innovation Sandbox Programme later in the year.

On the regulation front we have introduced the Individual Accountability Framework (IAF) and are finalising the review of the Consumer Protection Code. Two pieces of regulation people associate with looking back, these are in fact very much about ensuring the system is set up well for the future.

The IAF is all about helping underpin sound governance across the financial sector by setting out clearly what is expected of well-run firms. For both firms and the regulator it should be seen as a complement to the wider focus on governance, culture and behaviour. For the Central Bank our hope is that along with wider efforts, the IAF will help make firms take more ownership and responsibility for running their business and addressing any risks or deficiencies they may have. And as I have said before, in an increasingly technological and rapidly changing world, the need for effective governance underpinned by a strong ethical culture and robust systems of delivery is becoming more and more essential.

The Consumer Protection Code Review is building on the strong foundations of the Code – which is a cornerstone of the Central Bank’s consumer protection regulatory framework.[18] Our review is very much about modernising the code, reflecting the provision of financial services in a digital world. Our consultation on the changes to the Code closed last month; and we will publish a revised Code and Feedback Statement in 2025.

In addition to all of this we are transforming our supervisory approach. While our new supervisory model will of course remain risk based, it is evolving to deliver a more integrated approach to supervision, drawing on all elements of our mandate – consumer and investor protection, safety and soundness, financial stability and integrity of the system.

This new approach, where integrated teams will supervise with respect to all elements of this mandate, will position us better as an organisation to meet our objectives to ensure consumers of financial services are protected in a changing, increasingly complex and interconnected financial landscape. It will maximise the benefit of our integrated mandate – enabling us to continue to deliver on our mission and ensure the financial system operates in the best interests of consumers and the wider economy.

These changes are not just important; they are necessary – so that in a changing world we continue to deliver in the public interest.

Conclusion

So, to conclude – the banking sector has made admirable progress in addressing the issues of the past; but much work lies ahead in addressing the challenges of the future.

Profits have returned – which is a good thing for the resilience of the sector; but this has largely been down to the changed interest rate environment – which may not be here to stay. And the business model challenges that have faced the sector have not necessarily gone away.

The changing financial system and changing consumer expectations means transforming your systems and safely accelerating your digital offerings is no longer just necessary, but is quickly becoming an operational and strategic imperative.

And given the pace of change, now is not the time to further lag behind.

For its part, the Central bank is seeking to respond to this changing environment. So must you.

And with significant challenges lying ahead – we both have more to do.

-

[1] With thanks to Cian O’Laoide, James Flanagan, Paul Dolan, Shane Walzer and Stephen Sweeney for their help preparing these remarks and to Mary-Elizabeth McMunn, Simon Sloan, and Steven Cull for their helpful comments.

[2] Ratio of NPLs as a percentage of gross loans. These levels were reached even after the established of our Asset Management Company or ‘bad bank’ in the form of NAMA

[3] Scope: AIB, BOI and PTSB. Loss absorbing Capacity includes own funds and eligible liabilities; “Fully Loaded” CET1 Ratio is adjusted in 2014 to include preference shares.

[4] Central Bank data –comparing current lending with LTIs in excess of 4 to lending with LTIs in excess of 4 in the five years to 2007.

[5] See George Santanya – The Life of Reason: The Phases of Human Progress

[8] Central Bank Data March 2016 – March 2024

[12] Jorge Luis Borges: Other Inquisitions (1952)

[14] The old age dependency ratio is the population aged 65 and over as a proportion of the working-age population.