"Looking over the Horizon: the long-term outlook for the Irish economy" - Remarks by Governor Gabriel Makhlouf at University College Cork

30 January 2024

Speech

The following remarks were delivered during a visit to University College Cork on Tuesday 30 January 2024.

Good afternoon.1 It is a pleasure to be here today to talk about the long-term outlook for the Irish economy.

The economy has experienced a succession of large negative economic shocks since 2020 with the global pandemic followed quickly by a major inflationary surge in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine just under two years ago. The necessity for policymakers, households and businesses to deal with the immediate – and in some instances unprecedented – short-run challenges created by these crises meant that the attention given to major long-term challenges – and the planning and policy actions needed to address them – has been somewhat curtailed in recent years. In my remarks today, I would like to focus on the prospects for the Irish economy taking a long-term perspective: what are the key determinants of the growth outlook for the economy over the next 50 years? How will these be shaped by the transitions already underway linked to structural changes from ageing, climate change, digitalisation and changes in international trade patterns? And how can policy actions contribute to creating the conditions for sustainable growth in living standards over the long term?

Before I address these questions, let me first reflect briefly on current developments. Economic activity and inflation weakened in euro area in the second half of 2023. The short-term outlook points to stagnation in activity in the face of tighter financing conditions, weak business and consumer confidence and low foreign demand. Over the medium term the economy should gradually return to growth as both domestic and foreign demand recover. A broad-based disinflationary process is unfolding and is expected to continue during 2024 as the effects of past energy price shocks and other pressures fade. The pace of growth in labour costs will then be the dominant driver of core inflation. Overall, headline HICP inflation is expected to decrease from 5.4 per cent in 2023 to an average of 2.7 per cent in 2024, 2.1 per cent in 2025 and 1.9 per cent in 2026 based on the latest Eurosystem staff projections.

Following our latest meeting on 25 January, my colleagues and I (on the ECB’s Governing Council) decided to keep the three key ECB interest rates unchanged. The past interest rate increases continue to be transmitted forcefully to the economy. Tighter financing conditions are dampening demand, and this is helping to push down inflation. We consider that policy rates are now at levels that, if maintained for a sufficiently long duration, will make a substantial contribution to bringing euro area inflation back to target. Looking ahead, we should remain open-minded about the rate path, which is the essence of data dependence. With disinflation well underway, we are confident in sustainably reaching our target of 2 per cent.

Having displayed resilience throughout the overlapping shocks of COVID-19 and the onset of the war in Ukraine, the Irish economy has shifted onto a slower growth path in line with its current medium-term potential. Inflation declined significantly over the course of 2023. The effects of the initial commodity price shock have faded and the secondary impacts remain relatively contained, despite supply pressures in parts of the labour market still being evident. As the momentum of domestic economic activity ebbs, and the effects of tighter monetary policy both at home and abroad continue to materialise, the process of disinflation is expected to proceed at a more gradual pace over the next two years.

The Central Bank’s next Quarterly Bulletin will be published in early March and will set out our updated outlook for economic activity and inflation in Ireland over the short-term horizon of the next three years. For the remainder of my remarks today, I would like to consider the performance of the economy over a much longer time horizon: what have been the key determinants of growth over the last 100 years and what key factors will shape the economy’s prospects for the next half century?

Assessing the economy’s performance and prospects over a long-term horizon

Put simply, an economy’s long-run growth rate (and in turn the living standards of its people) is determined by the size of the population, the proportion of people in employment and the average amount of output produced per worker (or labour productivity). Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow (who sadly passed away last year) provided a framework in his influential work in 1956 for considering how these factors determine the economy’s long-term growth. This involves measuring the contribution of factor inputs (labour and capital) and the efficiency with which these factors are combined in production, also known as total factor productivity (TFP).2

Before looking to the future, it is useful to review briefly the realised performance of the Irish economy over the last century through the lens of this framework. Though not as affluent as sometimes portrayed by standard measures of economic activity such as GDP, by the end of 2023 the Irish economy was characterised by comparatively high income per capita in an international context and with a ratio of employment to the total population above that of the EU, US and UK. The path to this relatively favourable income and employment position has not been a smooth one.

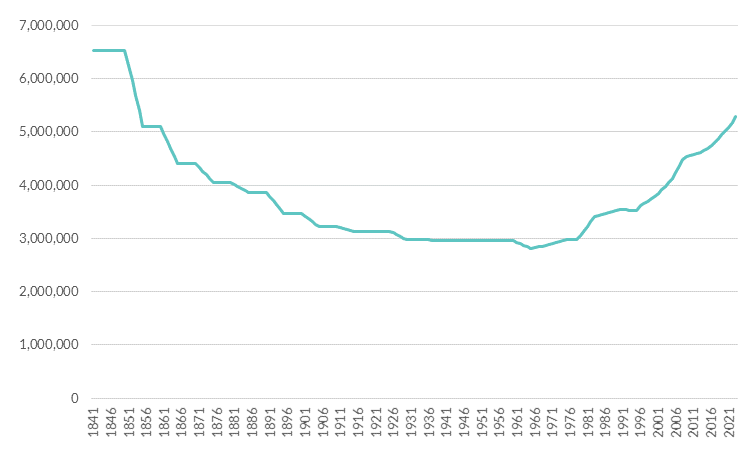

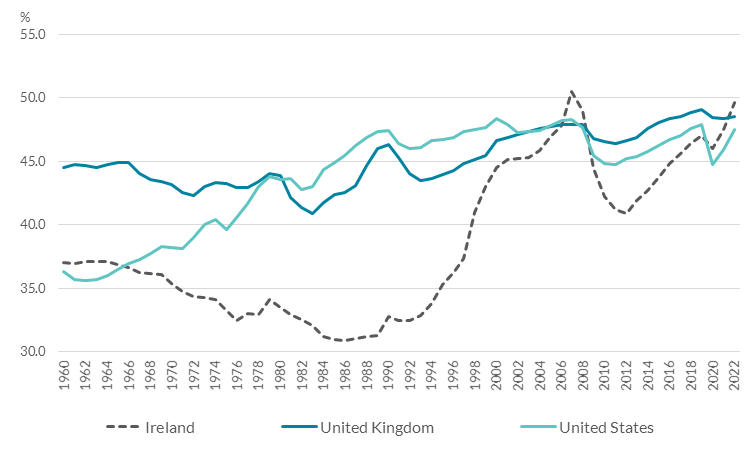

From independence up to the late 1960s, the economy experienced a long period of economic stagnation during which living standards in Ireland lagged behind those of most western European countries. Remarkably, the population declined right up to 1961 as high levels of net outward migration more than offset the natural increase in the population (births minus deaths) (Figure 1). At its low point that year, Ireland’s population had fallen to around half its pre-Famine level. The economy’s employment performance was equally dismal over this period with the level of employment in the late 1960s being below that attained 50 years previously at the foundation of the State. As a result, Ireland’s employment to population ratio at the beginning of the 1970s was around one-third lower than both the EU and US (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Total Population 1841-2023

Figure 2: Employment to Population Ratio

Confronted with the reality of decades of economic decline and large-scale emigration, a seismic economic policy shift began to take place from the late 1950s. As espoused in TK Whitaker’s famous 1958 paper Economic Development, this saw a move away from protectionism which was replaced instead by a concerted focus on enhancing foreign direct investment (FDI) and openness, increasing exports, boosting competitiveness and investing in human and physical capital.

This economic policy shift was given further impetus by Ireland’s accession to the European Economic Community in 1973. The performance of the economy improved in the aftermath of these major policy changes but the oil crises of that decade, procyclical fiscal policy and the resulting public debt crises of the 1980s impaired the economy’s performance up to the early 1990s. This manifested in persistently high double-digit unemployment and large-scale net outward migration in the decade from 1981 to 1991.

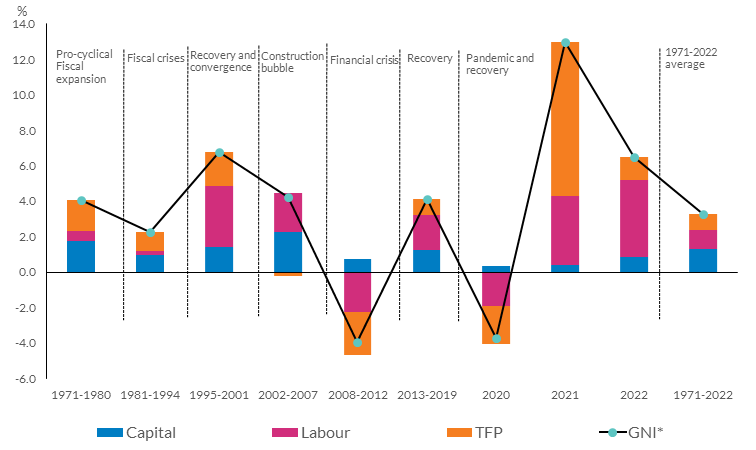

Figure 3: Historic Decomposition of Real GNI* Growth

From the mid 1990s until the early 2000s, the economy experienced a period of rapid growth that eventually delivered convergence in living standards with the rest of Europe. The ingredients of this turnaround in economic fortunes were multi-dimensional and included an increase in employment of workers with high levels of educational attainment (including workers from abroad), an increase in labour force participation particularly for women, a strong improvement in competitiveness coupled with an impetus to growth from high levels of inward FDI and favourable economic conditions in key trading partners. The accumulation of physical capital played a smaller role than employment and educational attainment in driving economic growth during this phase of economic convergence (Figure 3). The vastly improved economic performance during this period also reflected the correction of past policy mistakes that had contributed to high inflation and unemployment in the 1970s and 1980s.3

The economy continued to grow in the period up to 2008 but the unsustainable fiscal and financial conditions underpinning this growth eventually unwound, culminating in the 2008-13 economic and financial crisis that saw deep reductions in employment and a resumption of net outward migration for the first time since the late 1980s. Economic activity recovered gradually following this major recession but recent years have witnessed a succession of material negative economic shocks from the departure of the UK from the EU (the consequences of which are still being played out) followed by the pandemic and the inflation shock in the wake of Russian’s invasion of Ukraine.

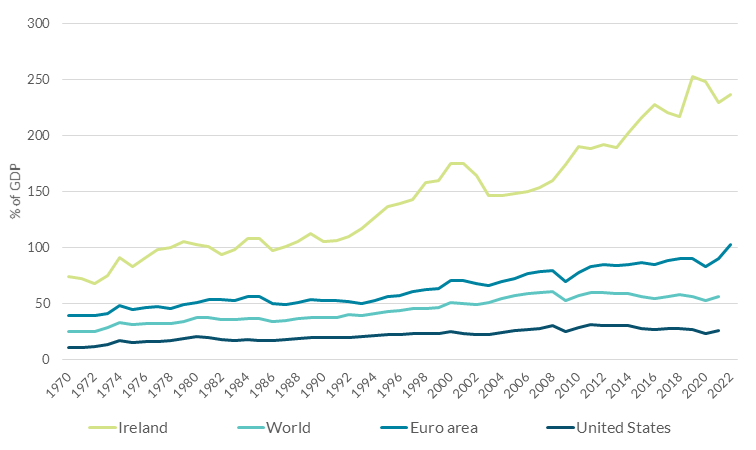

Through these successive negative shocks, the economy has demonstrated considerable flexibility and resilience. Economic growth in the past decade has been sustained by increases in labour force participation for women and older workers coupled with high levels of net inward migration of workers with advanced educational attainment. Over the last five years, non-Irish nationals have accounted for over two out of every five new jobs in the economy. Moreover and although sometimes obscured in headline economic statistics, over the past decade Ireland has benefitted from further growth in international trade and a trend towards enhanced global economic interconnectedness which continued up to recently (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Long-run trend of increased globalisation

The combination of a benign international trade environment and Ireland’s specialisation in fast-growing global sectors such as pharmaceuticals and ICT services has served to stimulate economic growth in the years since the global financial crisis. Overall, looking at the period from the financial crisis up to the pandemic, average growth was lower than during the 1995-2001 convergence phase but the composition of growth in both periods is not dissimilar with employment and labour force participation being the main driver (Figure 3).

Summing up, increases in population driven by high levels of net inward migration, improved educational attainment and labour force participation and the economy’s capacity to harness the benefits from enhanced global integration all played a prominent role in raising national output following decades of stagnation in the first half century after independence. Although economic growth has been interrupted by multiple severe crises, the same factors have continued to play a central role in explaining Ireland’s growth performance over the last 50 years.

The long-term outlook for the Irish economy

Four major structural changes already underway will shape the long-term growth prospects for the economy over the next 50 years: transitions in demography, in climate and in technology as well as the fragmentation of global trade. The future pace of growth in output and living standards will be determined by the impact of these transitions on the key determinants of long-term growth including the population and employment, the rate of productivity growth and investment in the capital stock. Public policy has a central role to play in facilitating the adjustment of the economy to these changes in a manner that supports sustainable growth in employment and incomes (a topic I will return to later).

(1) Demographic change and ageing

The demographic dividend which has underpinned growth in the Irish economy over the last fifty years is fading and will ebb further as the population ages rapidly from the end of this decade. The demographic transition is already underway. Twenty five years ago, the number of people aged 20-49 years was roughly 70 per cent greater than the number aged 50 years or over. Today, that figure has fallen to around 20 per cent and the two groups are projected to become the same size within the next decade (in 2034).

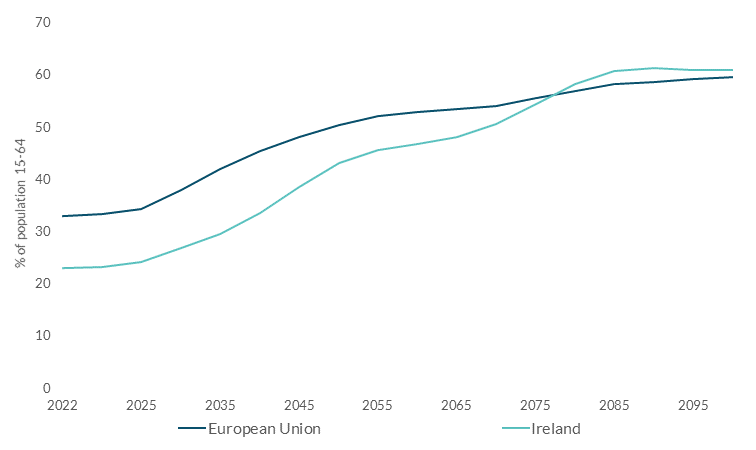

The old age dependency ratio – i.e. the population aged 65 and over as a proportion of the working-age population – is expected to increase from around 23 per cent in 2022 to 27 per cent in 2030 and to 47 per cent by 2060 (Figure 5). This implies that the number of people of working age for each person aged 65 and over in Ireland will drop from around four currently to just over two by 2060. The growth in the working age population is expected to fall sharply from an annual average rate of 1.4 per cent from 1995-2023 to just 0.2 per cent from 2030, with population growth turning negative in the late 2030s.

Figure 5: Old age dependency ratio, EU and Ireland

Slower growth and the projected eventual decline in the working-age population represents a deep structural change that will ripple through the economy in several ways. Older people have different patterns of work, spending and saving than younger groups and so a rising share of the population in older cohorts will influence how the economy works. I would like to focus here on the labour market effects of the demographic transition.

The projected slowdown in population growth, unless offset by increases in net inward migration, will lower the size of the working age population and thereby directly reduce the economy’s potential growth. Based on the latest long-term demographic projections for Ireland from the European Commission, employment growth is forecast to fall to 0.6 per cent in 2030 and just 0.1 per cent in 2040 before turning negative in 2050.4 This would represent a sharp slowdown in employment growth from the 3.1 per cent annual average growth recorded in the decade from 2013 to 2023. Labour force participation might also decline as the population ages although there are offsetting forces. Participation tends to be at its highest for those of prime working age (the cohort aged 25-54), lower among under 25s (due to participation in education) and in low single digits for those aged over 75. Recently, overall labour force participation has been boosted by increases in age-specific participation for older workers with high levels of educational attainment. This is a positive development but on its own may not fully offset the effect of population ageing, particularly as the transition to an older workforce accelerates after 2030.

The demographic transition will also impinge on productivity growth – the amount of output produced per worker. As the workforce ages, the benefits of know how and experience may be offset by depreciation of skills and more limited innovation, although the balance of these effects is likely to differ by occupation and sector. Improved longevity and extended years of healthy life have the potential to counterbalance the negative impact of productivity on ageing. In Ireland and in the euro area, the attachment to the labour force has increased for older workers, particularly women. Healthy ageing is likely to be a key contributor to longer working lives.5

In addition to these effects operating through the labour market, ageing is likely to continue to exert downward pressure on the natural rate of interest, i.e. the real rate of interest consistent with the economy operating at its potential and with price stability. The natural rate has been on a consistent steady decline in the euro area since 1999. Ageing affects the natural rate through a number of channels. As the proportion of the population in younger age groups shrinks, productivity, innovation and investment are likely to reduce. Moreover, an older population with rising longevity and longer retirement periods is associated with higher savings. Together these effects are likely to reinforce the existing decline in the natural rate. This trend presents challenges for the monetary transmission mechanism by reducing the power of conventional monetary policy to stabilise the economy in the face of demand shocks.6

Lastly, mounting ageing-related public spending along with an eroding tax base from a shrinking labour force will put pressure on the public finances. On the taxation side, slower economic growth from an ageing population will lower government revenue. At the same time, an older population will require increases in public expenditure to meet higher costs in the areas of healthcare, long-term care and pensions. To deliver existing levels of public services to an older population, the Department of Finance estimates that by 2030 additional expenditure of €7 billion to €8 billion will be required relative to the outlay in 2019. The fiscal costs of ageing will continue to increase thereafter with overall age-related government spending expected to rise to just under 30 per cent of GNI* in 2050, up from 21.4 per cent in 2019.7

(2) Macroeconomic effects of physical impacts from climate change and the transition to a net-zero economy

Climate change is a major structural force that is already affecting the economy and broader society. As confirmed recently, the average global temperature in 2023 was the warmest since records began in 1850. In Ireland, 2023 was also the warmest year on record since data were collected 124 years ago. These latest troubling milestones provide further clear evidence of ongoing global warming linked to human activity.8

The rising frequency and severity of extreme weather events due to climate change is already affecting production and economic activity and raises uncertainty about the future distribution of economic shocks hitting the economy. Meanwhile, meeting the goals set by the Paris Agreement, and the associated requirement of achieving net zero emissions, will necessitate a deep – and in some cases disruptive – shift in production processes and consumer preferences away from carbon intensive goods and production methods towards more sustainable alternatives.

The economic analysis of the potential impact of climate change focuses on two types of risks: ‘physical’ and ‘transition’. Physical impacts of climate change could affect both supply and demand sides of the economy through damage to infrastructure and the capital stock, reduced labour productivity, slower human capital accumulation and diminished human health. Physical impacts are likely to raise inflation.9

Transition risks refer to the potential effects on the macro economy that may arise as it decarbonises and moves towards a net zero position. Against a backdrop of persistently high emissions levels, increasingly the evidence indicates that the transition will be more disorderly than previously expected, involving deeper and faster emissions cuts in order to meet current targets. Delayed action will lead to higher cumulative emissions and consequently amplify the climate-related physical risks to which the economy is exposed. This would increase the ultimate economic cost of the transition, relative to a smoother and more orderly adjustment.10 Mitigation policies by governments (such as subsidies and regulations to encourage adaptation of green investments) could reduce inflation and boost growth but this depends on the type and financing of investment. A further uncertainty relates to how physical and transition risks may interact with each other and whether this interaction could produce effects that are highly non-linear.

Already in Ireland, policies such as the phasing out of the use of fossil fuels in energy generation and schemes to encourage retrofitting of the housing stock have triggered significant changes in the energy production and construction sectors respectively, creating opportunities for new businesses and technology adoption as older carbon intensive systems are phased out. Higher investment in renewables should reduce energy prices over the long run as the economy becomes more electrified and the share of renewables in electricity generation reaches the government’s 2030 target of 80 per cent. However, failure to make sufficient progress towards net zero targets in the immediate future (and the world, including Ireland – as the Environmental Protection Agency reminded as last week – is not on track11) would require the abrupt implementation of more stringent policies in future, increasing the probability of ‘stranded assets’ and more dislocated workers and raising the ultimate costs of the transition.12 Moreover, concerns over the green transition may dampen investment due to heightened uncertainty.

Climate change will have implications for the labour market, in particular the transition to net zero will involve the reallocation of jobs and skills across specific activities and sectors. The precise impact of this will depend on the pace of the green (labour) transition, in particular, the speed of decarbonisation through the domestic supply of renewable energy. Labour productivity will also be affected, although the ultimate effect is uncertain. Increasing investment and employment in high-productivity domestic sectors (such as greener manufacturing) and decreasing employment in low productivity sectors could boost productivity but other changes, such as loss of the productive capital stock, could be negative for productivity.

Through all of these channels I have mentioned, it is clear that climate change will affect the financial system and I have spoken before about the multifaceted actions we are taking to tackle the challenges it poses.13

(3) Technological change and digitalisation

The rapid advance in the development and use of digital technologies represents one of the most profound changes in the global economy over the last 25 years. Digitalisation is being enabled by a range of emerging technologies that include cloud computing; high-performance computing; artificial intelligence (AI); machine learning, big data analytics and a range of other technological advances. These technologies make it feasible to automate and carry out in a more efficient way not only manual, routine tasks but also more cognitively challenging functions which previously only humans could do. This makes the most recent wave of technological progress different to previous episodes which tended to have a larger effect on routine tasks.

The digital transformation will have complex implications for all sectors of the economy (and society) that mean its overall economic impact is difficult to foresee. Digitalisation will create opportunities for increased productivity and growth, job creation, job specialisation as well as the emergence of entirely new sectors. At the same time, we should expect the transition to new technologies to be disruptive and involve some displacement of workers. The ultimate impact will depend on the extent to which the new technologies are complements or substitutes for labour.

Recent analysis by the IMF indicates that almost 40 percent of global employment is exposed to AI, with advanced economies generally both more exposed but also better positioned to leverage this technology than most emerging market and developing economies.14 In Ireland, the presence of well-established ICT manufacturing and services sectors suggests that there may be opportunities for the economy to harness the benefits of enhanced digitalisation, but realising these gains will not be clear-cut. Older workers, those with lower levels of educational attainment and reduced job mobility are likely to face challenges in response to the changing nature of work triggered by digitalisation.

(4) Global trade fragmentation

Trade globalisation – the trend towards increased interconnection in global trade – has ebbed and flowed over the decades. The period of industrialisation that lasted up to the early 1900s suffered a reversal in the interwar period when trade barriers and protectionism increased. The Bretton Woods era and the post war recovery resulted in trade liberalisation which accelerated in the period from 1970 up to the global financial crisis driven by the removal of trade barriers in large emerging economies including China and enhanced international economic cooperation, among other factors. Over the last decade, there is evidence that that global trade integration has plateaued.15

These fluctuations in the degree of trade integration over time differentiate this final structural transition from the other three I have discussed. In the case of ageing, climate change and digitalisation, these structural transitions are inherently persistent and in some cases irreversible. Although there is evidence of trade fragmentation and a risk that this intensifies, history shows that this is not inevitable and the choices made by policymakers can influence how trade integration evolves over the coming 50 years.

As a small, trading economy Ireland has prospered from free trade supported by an international rules-based system. The war in Ukraine, US-China tensions and conflict in the Middle East are resulting in shifts in patterns of trade and globalisation, intensifying pre-existing trade tensions and trends. As I have discussed previously, this is manifesting in more emphasis on self sufficiency and less reliance on extended global supply chains.

The EU has recently enacted legislation to promote the local production of key manufacturing inputs. These initiatives seek to help Europe achieve Open Strategic Autonomy, or the ability to protect its interests and adopt its preferred economic, defence and foreign policy without depending heavily on foreign states. This is a stated policy objective of the European Commission and is also being reflected in a reevaluation of State Aid rules. These developments are being mirrored in other parts of the world including in the US where legislation such as the Inflation Reduction Act has granted enhanced state support for green industry and semi conductor manufacturing.

These legislative initiatives underscore the shift towards reducing exposure to global supply chains including through the greater use of domestic inputs, the shortening of value chains and through the further diversification of input sources.

As a small open economy with an export-led growth model, the Irish economy is more exposed than others to negative external shocks arising from reduced global trade integration. More pronounced geoeconomic fragmentation would undo some of the gains from the greater interconnectedness that has stimulated growth in the Irish economy over the last 50 years. This reversal would be reflected in lower FDI, exports and productivity – all of which would serve to reduce overall economic growth. Fragmentation could also result in higher and more volatile inflation, particularly for a country like Ireland that is highly dependent on imports.

Policy choices to support sustainable long-term growth in output and living standards

In these remarks, I have only skimmed the surface of how these four transitions are likely to impact the growth path of the economy through their effects on labour supply, on investment and the capital stock and on productivity. Better understanding the channels through which these structural changes will affect the economy and financial system and their potential impacts will occupy much of the Central Bank’s analytical and research agenda in 2024 and in the years ahead.

Achieving sustainable economic growth that delivers improvements in living standards for the community as a whole, while at the same time the economy goes through these major structural transitions, undoubtedly presents government and policymakers with a tough task. I would like to finish my remarks with what I see as three key considerations for government and policy makers tasked with navigating the challenges ahead. Each of these involve inherent trade-offs and difficult choices to ensure that policy decisions enhance the economy’s resilience, thereby facilitating its adjustment to the major structural changes already visible.

First, policy choices should strive to reconcile short-term priorities with long-term objectives. Although short-term problems have a tendency to dominate policy debate, in devising solutions to these it is important to maintain a focus on long-term priorities. In relation to ageing, acting now while the demographic structure is relatively favourable and tax revenues are strong will make the transition to an older population structure more manageable and less costly. Similarly, addressing the climate transition will require substantial increases in public and private investment but delaying the necessary action would result in a more costly transition – environmentally and economically – in the longer term. In this context, the recent decision in Budget 2024 to establish the Future Ireland Fund (FIF) and the Infrastructure, Climate and Nature Fund (ICNF), with the use of excess corporation tax receipts, is a welcome step.

Second, with the economy operating in-line with its current medium-term potential, achieving the necessary scale of investment in housing and climate-related priorities, in addition to others, will require careful management and trade-offs to avoid unnecessary inflationary pressures over the medium term. This points to the importance of the Government recommitting to compliance with its 5 per cent net expenditure rule when setting its budgetary plans. Given the known demands on public resources that are emerging from the major structural changes I have discussed, it may be prudent to consider introducing measures that would contribute to increasing government revenue as a share of national income and broadening the tax base, in line with the recommendations of the Commission on Taxation. In the short run, this could help to ease inflationary pressures while public capital spending is being increased while at the same time helping to create a more sustainable tax revenue base and more resilient public finances with which future fiscal challenges can be addressed.

Third, public policy has an important role to play in making the broader economy and labour market fit for purpose in light of the challenges that lie ahead. It is clear that Ireland’s infrastructure in housing and other areas has not kept pace with the growth in population.16 This may be reducing labour supply by discouraging much needed inward migration. In addition to additional investment, there is an important role for policy in improving the planning, development and delivery of infrastructure at scale.

In relation to the labour market, investment in human capital, skills and life-long learning is instrumental in ensuring that the workforce and the economy as a whole can adjust to, and take advantage of, the opportunities of the climate and digital transitions. Policies that promote the retraining of workers and improve labour mobility are paramount, as recommended by the National Competitiveness Council and OECD, and acknowledged in Ireland’s National AI Strategy.17, 18

Similarly for firms, a focus on investment in research and development and fostering innovation would improve productivity, better enabling firms to adjust to the green transition and digitalisation.

A more fragmented global trading environment and where state aid rules are excessively relaxed would present a competitiveness challenge to the Irish economy and a threat to its ability to attract continuing high levels of inward FDI. This further points to the importance of improving the productivity and competitiveness of the economy to ensure it can deliver sustainable economic growth for the community as a whole over the longer term.

I will add a fourth, and final, consideration for government and policy makers: the EU’s Single Market. It is in Ireland’s interest to work with its EU partners on structural policies that will enhance the European economy’s supply capacity and make it more competitive. This would help to deepen the single market and boost productivity. Similarly, sustained progress towards Capital Markets Union and the completion of Banking Union is an imperative. It would strengthen the resilience of the financial system and improve the capacity of the wider economy to withstand future downturns and enable its adjustment to the looming challenges I have discussed today.

Conclusion

Let me conclude by going back to the start of these remarks.

The purpose of economic policy is to create conditions for the sustainable growth in the community’s living standards. That involves focusing on the fundamentals: price stability, prudent debt, a well-regulated and stable financial system, well-functioning and competitive markets. Our macroeconomic frameworks should have an intergenerational focus: managing the relatively short-term should go hand-in-hand with planning for the medium-term.

Ireland’s open economy is highly integrated into the global system; it is exposed to the economic effects of geopolitical tensions and changes in the pattern of international trade. Domestically, ensuring inflation continues to fall in an economy at full employment, while at the same time addressing capacity constraints in several sectors remains a priority. But while these challenges demand our attention now, it is important that we maintain a sustained focus on the major structural transitions that are already affecting the economy and will determine its future long-term growth path. These transitions are outside of the typical time horizon of consumers, businesses and indeed policymakers. Nevertheless, the task of tackling short-term problems while addressing longer-term challenges need not be presented as a dilemma.

This is because the decisions required to address short-term challenges can contribute to ensuring that the economy adjusts successfully to longer-term change. Reducing inflation and building resilience in the public finances would boost competitiveness and ensure authorities have the resources to take advantage of the opportunities of the major transitions underway, as well as mitigating the adverse effects of any disruption that will materialise. Structural policies to boost supply – at home and in the EU – would ease capacity constraints and increase productivity. And combined with investment in skills and training, it would reduce overheating risks and boost long-term growth.

The long-term is not all beyond the horizon: how you plan matters, the route you choose matters, what you decide matters. Addressing multiple challenges will involve difficult choices but planning well will help with choosing the right route and support sustainable improvements in living standards for the whole community.

1Many thanks to Thomas Conefrey, Niall McInerney, David Staunton and Graeme Walsh for their contribution to my remarks.

2See Solow, Robert. 1956. "A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Oxford University Press, vol. 70(1), pages 65-94.

3See Honohan, P. and B. Walsh, 2002. “Catching up With the Leaders: The Irish Hare”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, No. 1. Washington DC: The Brookings Institution and O’Gráda, C. and K. O’Rourke, 2021. “The Irish Economy Before and After Partition”, The Economic History Review, Vol. 75, no. (2).

4See European Commission, 2023. “2024 Ageing Report. Underlying Assumptions and Projection Methodologies”.

5See OECD, 2020. “Promoting an age-inclusive workforce”. Bodnár, K and Nerlich, C, 2020. “Drivers of rising labour force participation – the role of pension reforms” ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 5, 2020. Privalko, I., Russell, H. and B. Maître, 2019. “The Ageing Workforce in Ireland: Working Conditions, Health and extended Working Lives”.

6See Daudignon, S and Tristani, O, 2023. “Monetary Policy and the Drifting Natural Rate of Interest”. ECB Working Paper No. 2788, February 2023 and Lane, P.R., 2019. “Determinants of the Real Interest Rate.” https://www.bis.org/review/r191129a.pdf

7See Department of Finance, 2021. “Long-Term Ageing and the Public Finances.”

8See Met Eireann Annual Climate Statement

9See Kotz, M., Kuik, F., Lis, E and C. Nickel, 2023. “The impact of global warming on inflation: averages, seasonality and extremes”. ECB Working Paper no. 2821. Ciccarelli, M., Kuik, F. and C. Martínez Hernández, 2023. “The asymmetric effects of weather shocks on euro area inflation”. ECB Working Paper no.2798. Faccia, D., Parker, M. and L. Stracca, 2021. “Feeling the heat: extreme temperatures and price stability”. ECB Working Paper no. 2626.

10See Network for the Greening of the Financial System (NGFS): Scenarios for Banks and Supervisors, November 2023.

11See Environmental Protection Agency, “Ireland’s Climate Change Assessment: Synthesis Report”, 2023

12See Climate Change Advisory Council, “Annual Review”, 2023. Under its legally binding Climate Action and Low Carbon Development (Amendment) Act 2021, the Irish government committed to achieving a 51 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030 (relative to 2018 levels) and net-zero emissions no later than 2050. By 2022, emissions had reduced by 2.7 per cent compared to 2018. These reductions in emissions include LULUCF (Land Use and Land Use Change including Forestry).

13See Governor’s Blog, 2021. “Climate Change: Towards Action”.

14See https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2024/01/14/Gen-AI-Artificial-Intelligence-and-the-Future-of-Work-542379

15See “Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism”, IMF Discussion Note, 2023/1.

16See ESRI, 2024. “The National Development Plan in 2023: Priorities and Capacity”.

17See National Competitiveness Council, 2023. “Ireland’s Competitiveness Challenge 2023” and OECD, 2023. “OECD Employment Outlook 2023: Artificial Intelligence and the Labour Market”.

18See AI - Here for Good. A National Artificial Intelligence Strategy for Ireland.