Ireland’s fiscal policy

However, the effectiveness of the EU rules in an Irish context is limited. That is partly because they are defined using GDP, but also because they do not account for excess (or windfall) revenue. We know that GDP as measure of economic activity is not an accurate reflection of the reality of economic conditions as experienced by households and businesses in Ireland and fiscal rules based on GDP do not provide an effective anchor for budgetary policy. Moreover, estimates by Central Bank staff indicate that around half of current Corporation Tax receipts cannot be explained by domestic economic activity and allowance for these windfall revenues needs to be made when setting the fiscal policy stance.

These considerations mean that a credible domestic fiscal anchor is critical for Ireland. We are a small open economy in a monetary union, and domestic fiscal policy has a central role to play in keeping the economy on a sustainable growth path. Against this backdrop and in line with normal practice, I recently wrote to the Minister for Finance outlining three key points that I believe should be taken into consideration in framing the forthcoming Budget:

- set the overall budgetary stance in a way that doesn’t add to inflation;

- prioritise public capital spending alongside reforms to make that spending more efficient and encourage more

- private investment; and

- maintain a credible path for the public finances given the known risks, challenges and opportunities facing the economy over the medium-term.

Achieving progress across these three areas means specific choices and trade-offs have to be considered.

The economy

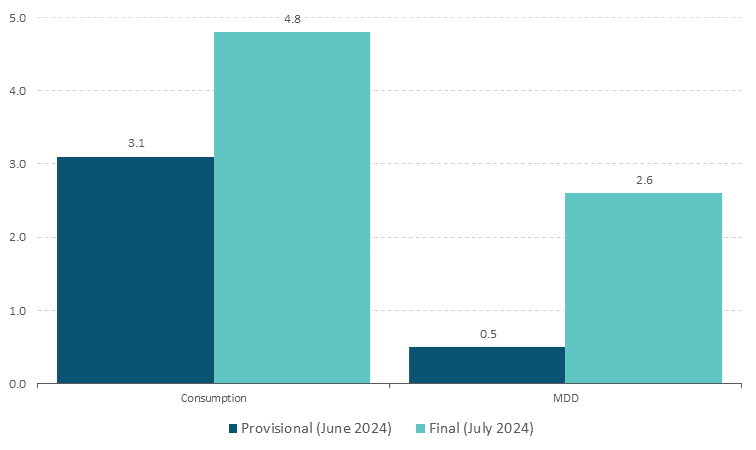

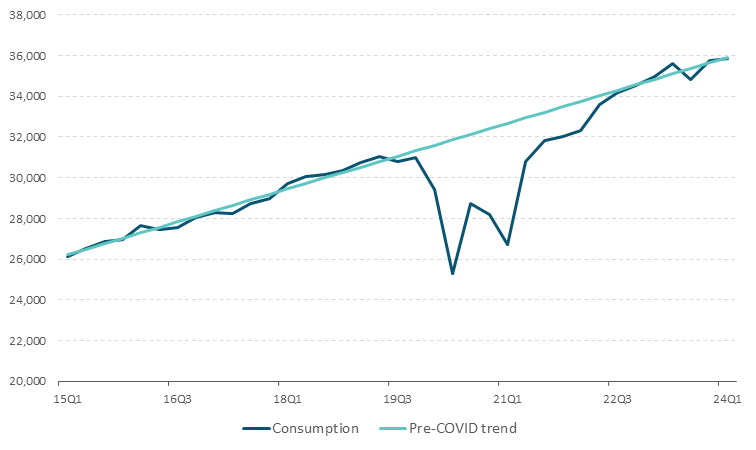

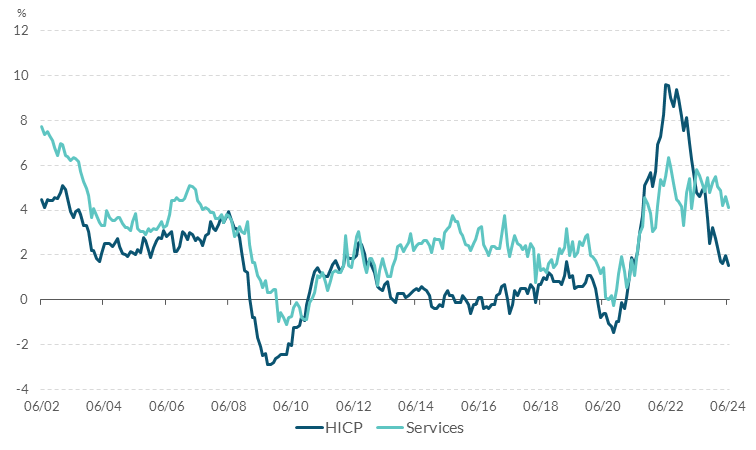

The economic backdrop to Budget 2025 is favourable. As outlined in our latest Quarterly Bulletin, the unemployment rate is forecast to stay around its current near-historic low level, households’ purchasing power is rising, and economic activity is growing steadily. Indeed, since I wrote my letter, revised National Accounts data indicates that the economy grew even faster (Figure 1) – and its post-pandemic recovery is further advanced – than previously estimated last year, with consumer spending restored to its pre-pandemic trend (Figure 2). Although headline inflation has fallen to below 2 per cent, services inflation – which is a good barometer of domestic prices pressures – has been slower to fall (Figure 3). Over the first six months of 2024, annual services inflation averaged 4.7 per cent. Persistent (and high) services inflation partly reflects the ongoing process of real wage catch-up, but is also consistent with the clear evidence of capacity constraints in the domestic economy and labour market following the rapid pace of economic growth since 2021.

Consumer spending revised up for 2023

Figure 1; Year-on-year per cent change

Figure 2; € billion Seasonally adjusted constant prices

Services inflation remains high

With the economy at full employment, and to guard against the risk of overheating, budgetary policy has a key role to play to manage overall levels of demand in the economy and to avoid unnecessarily stoking inflationary pressures in Ireland (which monetary policy, because it operates across the euro area, would not be able to address). Recent budgets have been expansionary, with expenditure (net of tax changes) growing well in excess of the Government’s 5 per cent rule. We estimate that the additional fiscal expansion over and above the 5 per cent rule stimulated demand at a time when the economy was already growing strongly and added an estimated ½ a percentage point to inflation in both 2022 and 2023.

Recently published analysis (PDF 1.07MB) by Central Bank staff shows that additional fiscal expansion above the 5 per cent rule would add to inflation and risk triggering potentially damaging overheating dynamics. While such a stance would boost activity in the short run, the erosion of competitiveness due to demand growing beyond the economy’s sustainable capacity could undermine the prospects for delivering growth in living standards over the longer term. Having – and sticking to – rules means we avoid short-term, year-to-year budgeting, where tax and spending decisions are set according to prevailing economic conditions. In the past, this approach resulted in incoming revenue windfalls being used to fund permanent spending commitments and inevitably contributed to fiscal policy magnifying the volatility of the economic cycle. In this context, I welcome the Government’s decision to establish funds for saving a portion of the windfall revenue.

Priorities for the long term

Although short-term issues have a tendency to dominate policy debate during the budgetary cycle, it is important to maintain a focus on medium-to-longer term priorities when addressing day-to-day issues.

The economy needs investment in public infrastructure to ease bottlenecks that are currently holding back opportunities for households and businesses to expand. The increase in total government spending over the last decade has been largely driven by rising current spending. At the same time, starting from a low base, there has been a marked increase in capital expenditure which grew by around 70 per cent in the five years to 2023. This investment has added to the public capital stock and will drive improvements in the productive capacity of the economy.

Government capital expenditure is projected to rise further over the medium term. In my view, accommodating the delivery of large increases in public capital spending in a sustainable way without overheating the economy requires making choices which prioritise infrastructure improvements in housing, water, energy and transport.

Along with the progress that’s needed in the areas of climate, housing and other infrastructure, the economy faces structural challenges from the ageing of our societies, the pace of digitalisation and the impact of geoeconomic fragmentation, all of which represent significant economic transitions. In my view, an objective of economic policy – at EU and individual Member State (MS) level – should be to build resilience across households, businesses and the wider economy in the face of these transitions. To meet this challenge, we must continue to focus on fundamentals. This means sound monetary policy that delivers low, stable and predictable inflation, complemented by robust macroeconomic and fiscal frameworks that underpin sustainable economic growth and resilient public finances.

As I discussed recently, over the long-run, the only way to increase living standards in a long-lasting way is by raising productivity. Domestic policy has a role to play in achieving this but so too do actions at EU and global level. Maintaining openness to trade and migration, and the broader multilateral systems that support this, along with well-regulated financial systems and well-functioning markets are prerequisites for managing the challenges that lie ahead. In the EU, the completion of the Banking Union and further developing the Capital Markets Union are important next steps.

Conclusion

To sum up, Budgets are about

the Government’s fiscal policy, the choices being made on the public finances

and the specific decisions on the allocation of resources. They are also important milestones for

economic policy-making in general and for the Government to lay out its

proposals for tackling longer-term structural challenges. As we approach Budget 2025, it is my view

that both near and medium-term priorities point to the need for a credible,

considered and future-focused approach to tax and spending decisions for the

second half of this decade that takes into account the risks, challenges and

opportunities facing the Irish economy and public finances.

Gabriel Makhouf

See “Eurogroup statement on the fiscal stance for the euro area in 2025”, 15 July 2024