Enabling a decade of higher investment – Speech by Deputy Governor Vasileios Madouros at TU Dublin

12 February 2026

Speech

Over the course of the next decade, we will need to allocate more of our collective resources towards domestic investment.1

In part, that is because of where we are coming from. Despite very strong economic growth in recent years, investment in key domestic sectors has been lacklustre.

But it is also because of where are going. Ireland, like many other countries, is facing profound structural transitions. Navigating these will require additional investment in the years ahead.

Raising Ireland’s domestic investment rate is an opportunity to strengthen the foundations – and resilience – of our economy into the future. But it is not without trade-offs.

It will require an orientation of economic policy that both enables higher investment and ensures that it happens in a sustainable – and sustained – manner.

The current state of the economy

Before I turn to investment specifically, let me focus on where the Irish economy is now.

In the context of what has been an unprecedent level of global policy uncertainty and an acceleration of geopolitical shifts, the economy has demonstrated remarkable resilience.

Overall, we expect the domestic economy – based on modified national income (GNI*) – to have grown by around 4.8% in 2025, a similar rate to 2024.

Exporting multinational companies have been adapting to the changing trading environment, and that adjustment has been benign so far, with exports growing overall last year.

Domestic demand grew steadily in 2025, supported by continued growth in real incomes as well as rising public spending.

While labour demand has softened, unemployment remains low by historical standards, at around 5%.

Looking ahead, our central expectation is that the economy will continue to expand, albeit at a slower pace, after several years of growth above potential.

But the risks around that central outlook are tilted to the downside.

The most pressing risks are external, with Ireland particularly exposed to further abrupt shifts in the international trading and investment environment, amid rising geopolitical tensions.

Domestic risks stem from increasingly binding supply-side constraints, especially in terms of infrastructure, which are limiting the growth potential of the economy.

Already, the theme of the need to increase investment is emerging. So let me turn to that.

Where we are coming from: a decade of subdued domestic investment

I’ll start by looking back: where we are coming from.

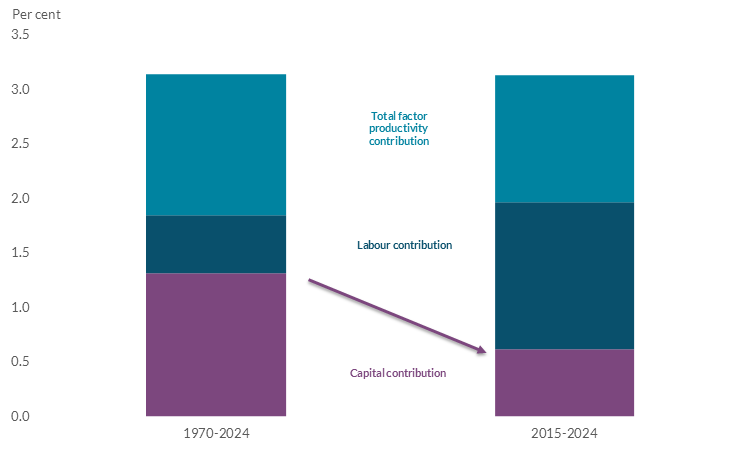

Over the past half century, investment has played an important role in driving growth in Irish living standards and supporting the transformation of the Irish economy.

Overall, it has accounted for around 40% of the growth in the economy’s productive capacity since the 1970s.

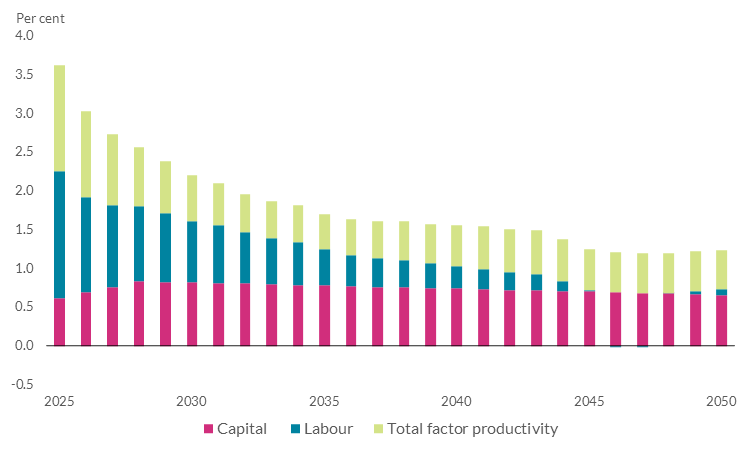

Chart 1: Historical decomposition of average potential output growth in Ireland

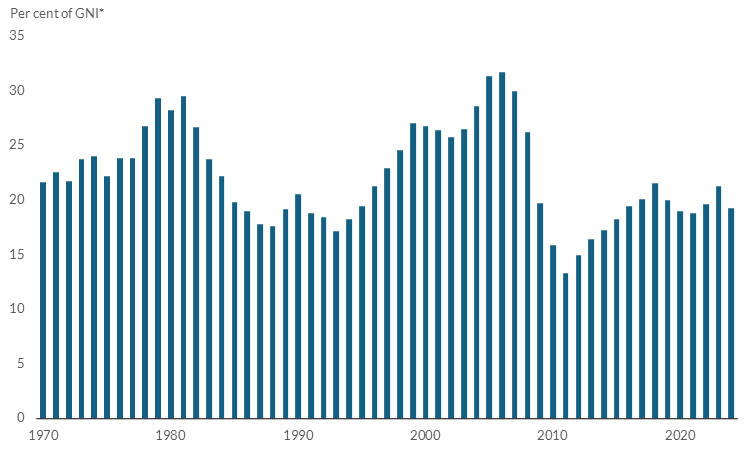

Throughout the course of that half century, however, there have been amplified swings in the economy’s investment rate.

Chart 2: Aggregate domestic investment rate in Ireland over the past half century

The latest swing was after the financial crisis, which followed an unsustainable, credit-fuelled property boom.

Since then, the recovery in aggregate investment has been relatively muted, even though the economy overall has performed very strongly.

In fact, investment has only contributed around 20% to growth in potential output over the past decade – around half of its historical average.

To better understand where we are coming from, it is useful to look beyond aggregates. So let me take a sectoral lens.

Public investment

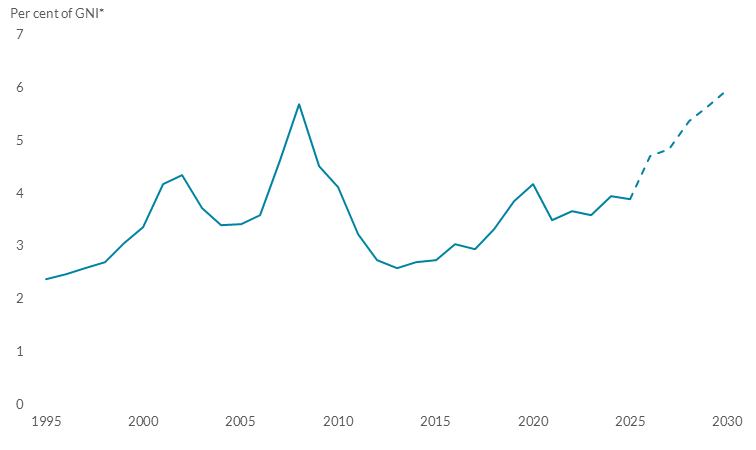

Starting with the public sector, the fiscal crisis that accompanied the financial crisis led to a sharp contraction in public investment.

Chart 3: Public investment has gradually recovered and is expected to increase significantly under the NDP

Indeed, public investment is typically amongst the first areas of public spending to be cut amid a broader fiscal retrenchment.

This has been one of the most persistent costs of the financial crisis, and we are feeling the consequences today.

Amid a strong recovery, and faster than expected population growth, our core infrastructure – whether it is housing, energy, transport or water – has become increasingly strained.

Addressing those infrastructure needs matters for people and businesses across the country, and for the long-term success of the economy.

In response to those shortfalls, and as the public finances have improved, the government has rightly outlined a significant planned increase in public investment over the next decade.2

Household investment

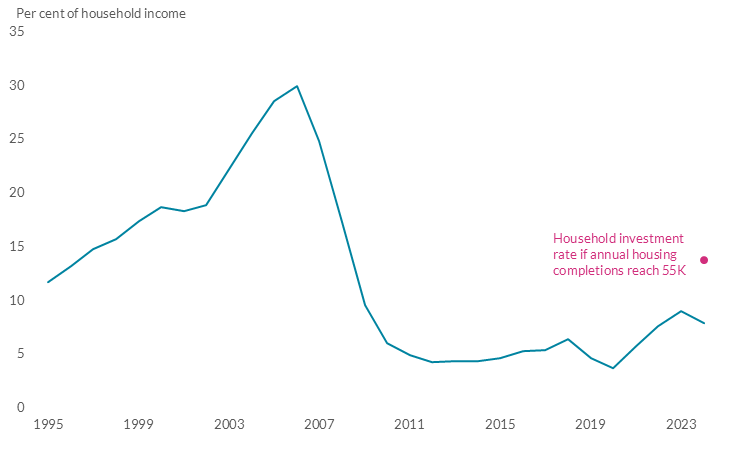

Turning to the private sector, the investment rate of households, while recovering from the lows of the financial crisis, remains well below historical averages.

Chart 4: Amid a slow recovery in housing supply, the household investment rate has remained subdued since the crisis

At its core, that stems from the persistent challenges in the housing market – because housing is the main component of real investment by households.

To be clear, the low investment rate by households is not due to a lack of demand. Far from it. Demand has been very strong, as evident by the increases in both rents and prices.

Rather, it reflects the slow recovery in housing supply since the financial crisis. That has constrained household’s ability to invest in new housing.

Increasing housing supply has been, and remains, a policy priority for the government. And housing output increased to around 36½K new homes last year, which is welcome.

But it remains below estimates of the underlying demand for housing, which stand at around 50-55K new homes annually.3

Reaching those levels of housing supply will also imply an increase in the investment rate of the household sector over the course of the next decade.

Business investment

Next, let me turn to business investment.

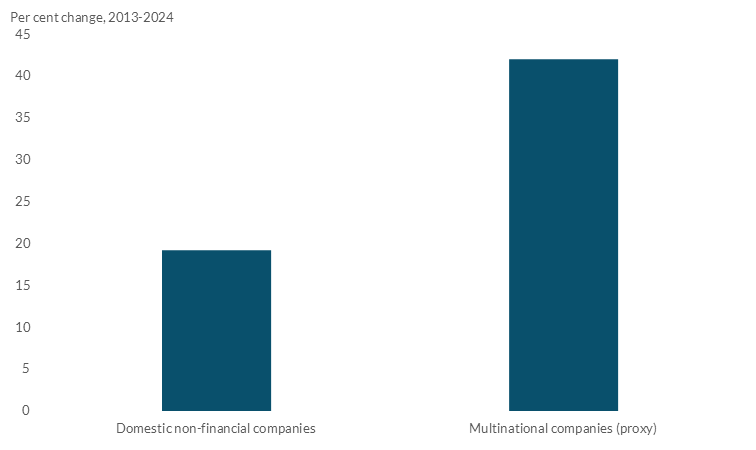

Here, there is a marked difference between the multinational sector of the economy and indigenous businesses.

Since 2013, (modified) investment by multinational companies has increased twice as fast as investment by indigenous companies.

Chart 5: The recovery in private business investment since the crisis has been driven by multinational companies

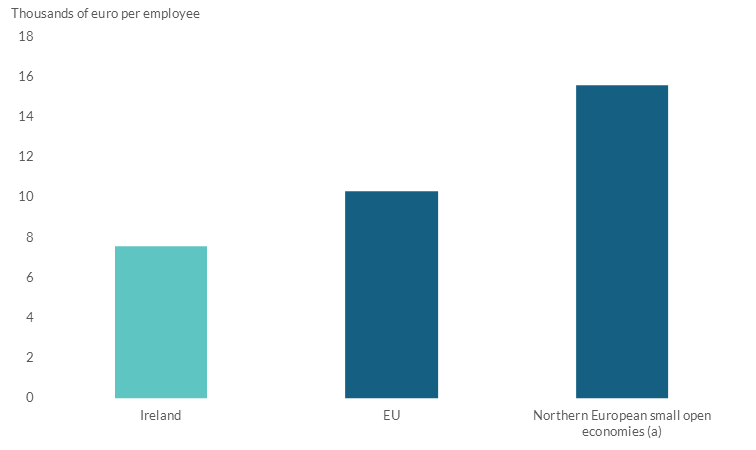

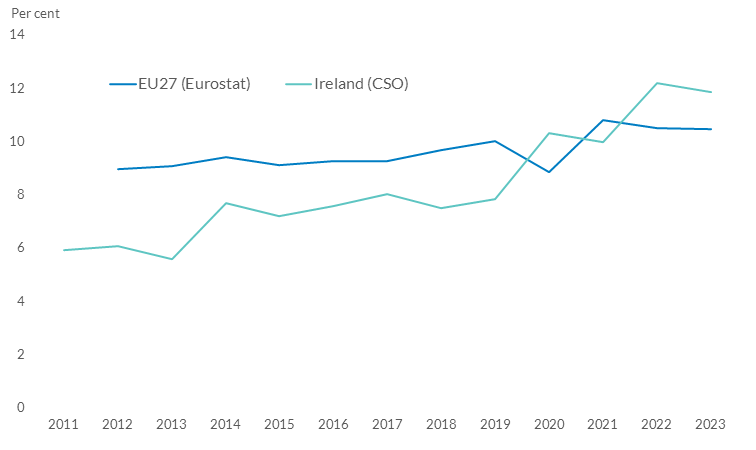

Cross-country comparisons also point to relatively muted levels of investment by indigenous companies.

The average domestic company in Ireland invests around €7,500 per employee. That is 25% below the average domestic company across the EU.

Chart 6: Investment per employee by domestically-owned companies in Ireland is below the EU average

This is partly due to the structure of economy, with domestically-owned firms typically being smaller than in peer countries, given the large presence of multinational companies in Ireland.

Of course, that dual nature of the Irish economy, in and of itself, entails vulnerabilities, if multinational activity is not complemented by a dynamic domestic sector.

Moreover, research that controls for company-specific factors, such as size and sector, still finds an investment gap between indigenous companies and European peers.

That is concentrated in investment in knowledge-based capital, such as research and development.4

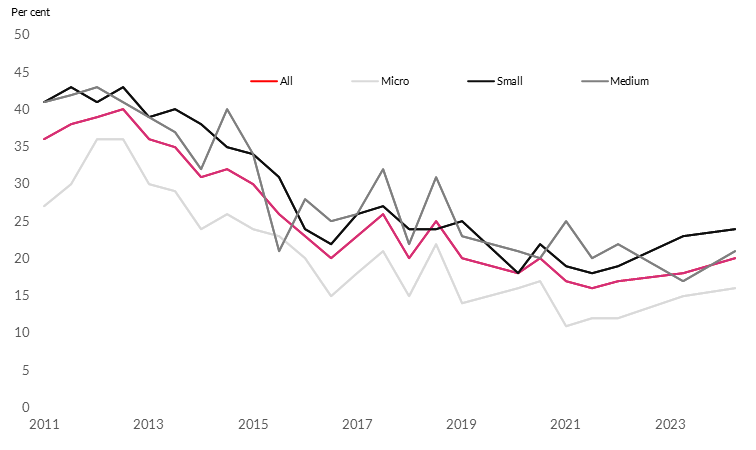

The weakness in investment by indigenous companies appears to be driven mainly by factors related to businesses’ willingness to invest, rather than factors related to the supply of credit.

Credit demand has been low amongst SMEs over several years, indebtedness has fallen markedly, while deposits have increased substantially.

Chart 7: Credit demand by Irish SMEs has been relatively low, for a number of years

Consistent with cautiousness amongst businesses, in survey evidence, one in two Irish SMEs see uncertainty as a key barrier to investment.5

In part, this cautiousness has been due to the various shocks businesses have had to navigate over the past decade, including Brexit, the pandemic, the energy crisis, and the current geopolitical environment.

Analysis by Central Bank colleagues suggests that attitudes to risk and recent firm performance are much more important determinants of SME investment, relative to credit constraints.6

Financing frictions, however, might be more prevalent in relation to equity financing, including scale-up financing.

In our engagement with start-ups, for example, the availability of scale-up financing for innovative companies is often raised as an issue, mirroring broader patterns in Europe.7

Ultimately, the comparatively low investment rate by domestic businesses – especially in knowledge-based capital – matters for productivity, at a firm level and an economy-wide level.8

And productivity of domestic companies is around 15% lower compared to businesses in other small, open European economies.9

This also points to the importance of increasing the investment rate of domestic businesses in the decade ahead, especially in knowledge-based capital.

To summarise, we are coming from a period of subdued investment in key domestic sectors, all pointing to the need to raise the investment rate over the coming decade.

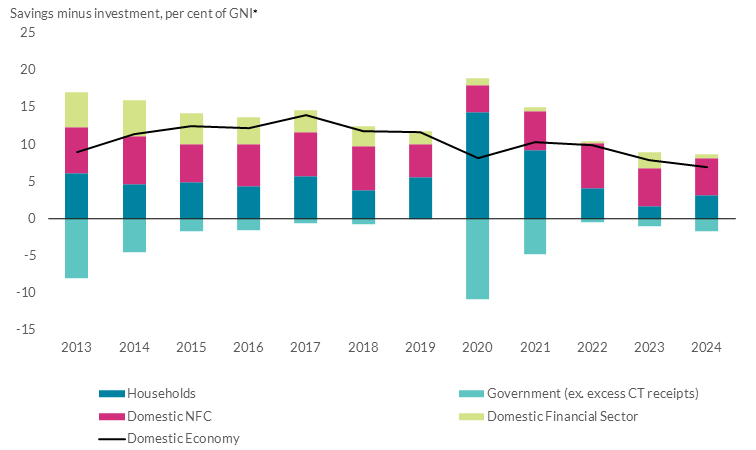

Indeed, in aggregate, domestic businesses and households save significantly more than they invest.

Chart 8: Irish households and domestic businesses save more than they invest

Those excess savings are, in turn, exported to the rest of the world, as reflected in Ireland’s (modified) current account surplus.

To me, that is a further signal pointing to the scope that exists to sustainably increase the domestic investment rate into the future.

Where we are going: the need for investment to navigate structural transitions

Let me now turn to the future. Like many other countries, Ireland has to navigate profound economic and societal shifts in years to come.

First, demographic changes.

Ireland’s population is ageing at amongst the fastest rate in the EU.

As that happens, the potential growth rate of the economy is expected to slow significantly over the next few decades.10

Chart 9: The potential growth rate of the economy is expected to slow markedly, driven by population dynamics

Under a baseline scenario, it could slow to around 1.2% by 2050, less than half its current rate. That matters for living standards.

Investment, including in knowledge-based capital that can boost productivity, is one of the key levers that can offset that decline over the next few decades.

Second, an increasingly fragmented global economy.11

Ireland has benefited enormously from its openness, its growing integration into global value chains and investments by multinational companies.

The shifting geoeconomic environment has the potential to reshape trade and investment flows, with competition for foreign investment becoming increasingly fierce.

That requires investment in our infrastructure, for Ireland to remain attractive as a destination for foreign investment.

It also requires investment by indigenous business, to enhance productivity and strengthen their contribution to domestic economic activity, supporting economy-wide resilience.

Third, climate change and the transition to net zero.

Mitigating climate change will require decarbonisation of our economy, from retrofitting our homes, to transitioning to clean energy sources, to electrifying our transport.

Adapting to a changing climate will require building our flood defences, protecting against rising sea levels and coastal erosion or adapting agricultural practices to a changing climate.12

And, finally, digitalisation.

The current wave of transformative technologies, including artificial intelligence, have the potential to substantially boost productivity and economic growth.

But adoption of these technologies requires investment. As does further innovation, to expand the frontier of technological possibilities.

These are all profound economic and societal transitions – and a common denominator in terms of how we navigate them is higher investment.

How to get there: raising Ireland’s domestic investment rate sustainably

This context then begs the question: what does the need to increase investment over the next decade imply for the orientation of economic policy?

Ultimately, policy should aim to enable a rising domestic investment rate in a sustainable – and sustained – manner.

And, importantly, this not just about domestic policy. It also about actively contributing to, and supporting, efforts to strengthen the European economy, of which we are a core part.13

Let me highlight four dimensions.

First, creating the necessary fiscal and economic space for the increase in investment.

For Ireland – a small, open economy in a monetary union – fiscal policy has a key role to play in achieving that.

That requires prioritising investment, within an overall fiscal envelope that does not add too much to demand when the economy is operating close to capacity.

Under the Government’s updated Medium-Term Fiscal and Structural Plan, overall net spending is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 6.7% from 2026 to 2030.14

Within that, it is not just public investment that is growing quickly. Current spending is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 5.9% over the same period.15

These growth rates exceed the potential growth rate of the economy – at a time when the economy is already performing well.

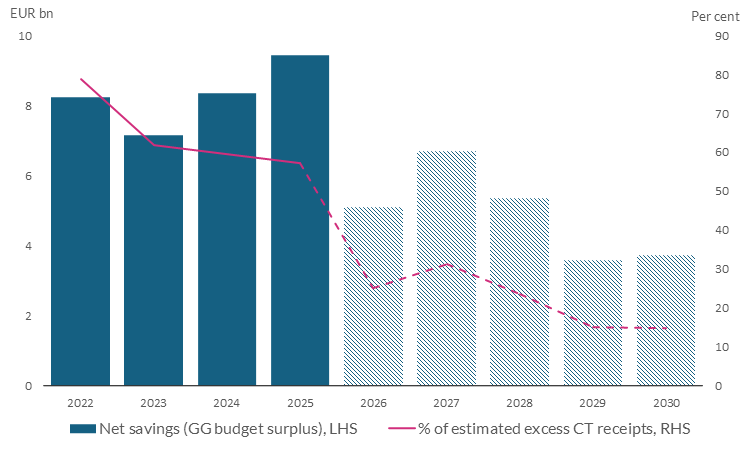

Such a stance risks creating an underlying vulnerability in the public finances, as it relies on spending an increasingly large share of excess corporate tax receipts, which are potentially very volatile.

Chart 10: The government’s headline budget surplus (net savings) will fall as a share of excess corporate tax receipts

It also risks contributing to domestically-generated inflationary pressures.

If the economy continues to perform well, raising investment – while managing those risks – will require more difficult, offsetting choices on current spending or tax revenues in future budgets.

That would also better enable the building of fiscal buffers, which could be used to maintain continued funding for investment in future downturns.

The government’s Infrastructure, Climate and Nature fund is a welcome policy initiative in this respect.

Ultimately, building sufficient fiscal buffers can guard against the “start-stop” patterns of public investment we have seen the past, which is costly in the long term.

Second, focusing on the efficiency of investment delivery.

From a public infrastructure perspective, financing is only one part of the equation. Efficiency of delivery is equally important.

Indeed, it is clear that delays in public investment projects have been commonplace in Ireland.

Reducing these delays and improving efficiency would ensure that the benefits of higher public investment accrue sooner and have a larger overall positive impact on the economy.16

This speaks to the implementation of the recommendations of the Accelerating Infrastructure Taskforce, which cover a range of dimensions, including legal and regulatory reforms.

Similar enabling structural policies – such as the implementation of the legislated planning reforms – are also needed to enhance the efficiency of private investment.

Third, fostering domestic business dynamism.

A policy orientation towards strengthening the contribution of Ireland’s indigenous businesses to the economy, complementing FDI activity, will be important over the next decade.

A key foundation is continuing to foster an environment that enables new firm entry and the growth of young firms, making entrepreneurship more appealing and attainable.

There are some positive sings here, with the birth rate of new companies gradually increasing and – after many years – now exceeding the EU average.

Chart 11: The birth rate of Irish companies has recovered in recent years

Making R&D and innovation policies more SME-friendly, as suggested by the OECD and the National Competitiveness and Productivity Council, can help reduce the investment gap in knowledge-based capital amongst domestic companies.17

This needs to be complemented – at a national level – by a continued focus on education and life-long learning, to ensure people have the right skills for the jobs of the future.

Indeed, while I have not focused on human capital today (that is another speech in and of itself), this has been a key factor in Ireland’s success, and it is important that it is maintained.

Beyond domestic policy, progress at a European level matters hugely.

As you know, more than three decades after the creation of the Single Market, trade barriers within the EU remain significant.18

Deepening and further integrating the Single Market will enable European – including Irish – companies to scale.

This is crucial, because scale can enable businesses to flourish.

For European, including Irish, companies to genuinely perceive their ‘domestic’ market as one of 450 million people, concrete progress is needed to strengthen the Single Market.

Finally, ensuring financing for investment is available and sustainable, through the cycle.

Investment, of course, requires financing.

As I mentioned earlier, there are significant savings in the Irish economy, if the investable opportunities are there.

But, especially for innovation-related investment, the nature of financing matters.

Bank financing is typically less well suited for innovative projects, given their higher risk and lack of tangible collateral.19

This is why progress on the EU’s Savings and Investment Union policy agenda is critical.

That aims to foster deeper and more integrated capital markets across the EU, helping to unlock private capital and facilitate investment, including in new technologies.

Finally, it is important that financing of higher investment is sustainable, through the cycle.

The lessons from history – including our own history – are plentiful. Fragilities in financing of investment can lead to economy-wide damage.

Resilient finance that is able to provide services to the economy, both in good times and in bad, serves the public interest best.

This has been – and will continue to be – our core focus from a regulatory and supervisory perspective at the Central Bank.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

Investment is critical to the long-term success of any economy and to support growth in living standards. That principle is timeless, but it is particularly relevant for Ireland now.

The next decade offers an opportunity to strengthen the foundations, and resilience, of our economy into the future.

That will require an economic policy orientation that enables allocating a greater share of our collective resources towards domestic investment, and doing so in a sustainable manner.

Thank you for listening.

[1] I am very grateful to Thomas Conefrey, Niall McGeever, Martin O’Brien, Sean O’Sullivan and Cian Ruane for their advice and help in preparing these remarks, as well as other colleagues at the Central Bank for their comments and suggestions.

[4] See Gargan et al (2024) ‘A cross-country perspective on Irish enterprise investment: Do fundamentals or constraints matter?’, The Economic and Social Review, Vol. 55, No. 2, pp. 173-215.

[8] See, for example, Lööf et al (2017) ‘CDM 20 years after’, Economics of Innovation and New Technology, Vol 26, No. 1-5.

[9] See Lawless (2025) ‘Hare or tortoise? Productivity and growth of Irish domestic firms?’, The Economic and Social Review, Vol. 56, No. 1, pp. 139-161.

[15] Ibid. This is expressed on an Exchequer basis.