The Macrofinancial effects of climate change in Ireland: What have we learned? – Speech by Deputy Governor Vasileios Madouros

25 November 2025

Speech

Good morning everyone.1

I am delighted to join you here today for this year’s Climate Finance week.

“The scientific evidence that climate change is a serious and urgent issue is […] compelling.”

“The benefits of strong, early action on climate change outweigh the costs.”

And “the choices made in the next 10-20 years […] will affect greenhouse gas emissions for the next half-century.”

These are not my words. And they are not recent words.

They are key conclusions from the Stern Review on the “Economics of Climate Change”.2

That was published almost two decades ago now.

Fast-forward to today, and we know that greenhouse gas emissions globally have not followed the path advocated for at the time.

As a result, the planetary, societal and macrofinancial risks from climate change have intensified over the past two decades.

Central banks and regulators globally – including ourselves – have made a concerted effort in recent years to strengthen our understanding of the macrofinancial effects of climate change.

This is an essential building block to allow us to take the appropriate actions needed to deliver our mandate.

So, in my remarks today, I will focus on those macrofinancial effects.

Progress towards decarbonisation has been slower than intended by the Paris Agreement

The starting point for that, of course, is the scientific evidence on human-induced climate change.

Today’s event marks a decade since the Paris Agreement in 2015, a landmark moment in the global fight against climate change.

It is important to recognise that we have seen tangible outcomes from countries’ collective actions since then, illustrating what can be achieved when nations come together.

Global greenhouse gas emissions are now projected to be around 12 per cent below 2019 levels in 2035. This compares to a projected increase in emissions of between 20-48 per cent, before the adoption of the Paris Agreement.3

Put differently, we are no longer on a trajectory towards the very worst-case scenarios that were once feared.

I emphasize that because – in Dr. Jane Goodall’s words – “without hope, we fall into apathy, and do nothing”.4

However, it is also clear that we have not done enough.

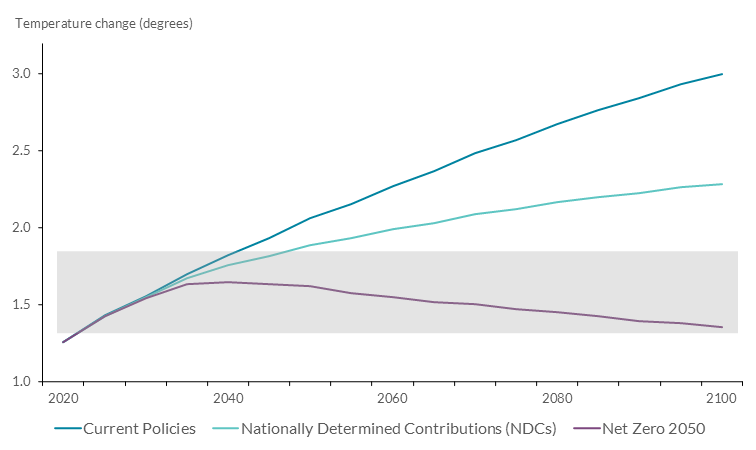

Global warming projections over this century, based on the full implementation of countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), exceed 2°C (Chart 1). 5

Chart 1: Projected global temperature change under different scenarios

Source: NGFS Phase 5 Scenario Explorer

Rising temperatures, more frequent and severe weather events, and disruptions to communities, economies and financial systems remain pressing concerns.

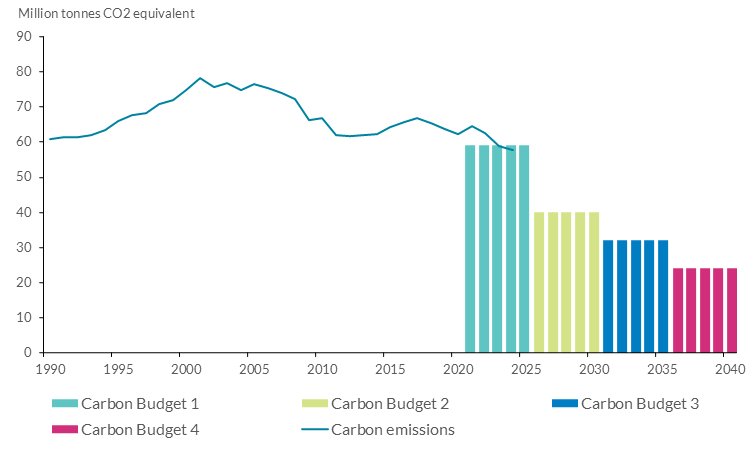

In Ireland, we have also made progress in reducing carbon emissions, which are down around 12% since 2018 (Chart 2).6

Chart 2: Ireland's greenhouse gas emissions and carbon budgets

Source: EPA.

Over the same period, our population has grown by around 10% and the size of the domestic economy by around 30% in real terms.

So we have seen a very positive decoupling between economic activity and emissions.

However, the Climate Change Advisory Council’s latest assessment is clear that Ireland is not on track to meet its EU and national emissions reduction targets by 2030.7

And that we will exceed the carbon budget allocation for 2021-2025.

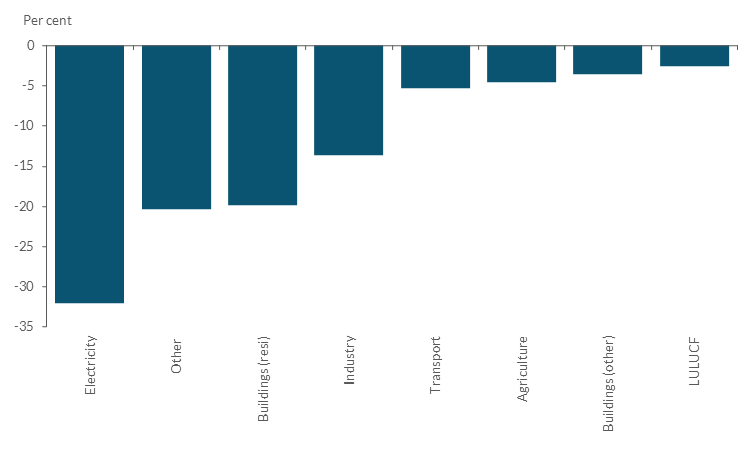

Progress across sectors has been uneven, with transport and agriculture, which collectively account for approximately 55% of Irish emissions, having seen smaller emission reductions (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Sectoral changes in emissions in Ireland, 2018-2024

Source: EPA

The macroeconomic costs of climate change outweigh those of the transition to net zero

Let me now turn to our understanding of the macrofinancial effects of climate change and the transition to a climate-neutral economy.

The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) – a coalition of central banks from around the world, including ourselves – has been instrumental in the journey of deepening our understanding of the macroeconomic effects of climate change.

The NGFS has developed a set of macroeconomic scenarios that assess the potential economic impacts of climate-related physical and transition risks.

Let me draw out three key insights from this work.

First, the global macroeconomic costs of climate change are material.

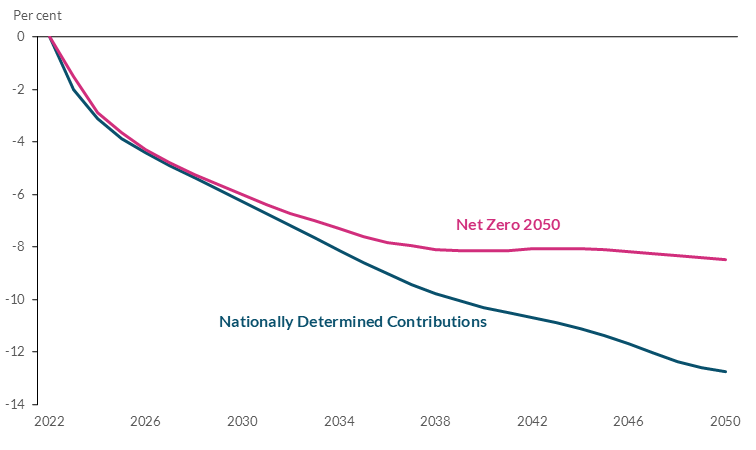

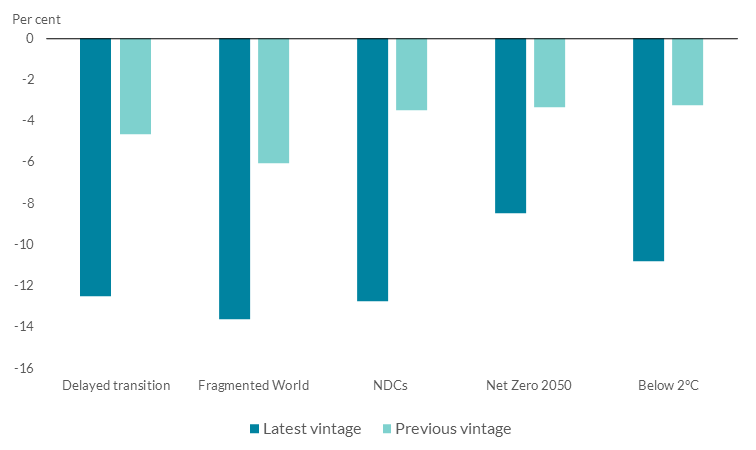

Under a scenario consistent with current nationally-determined contributions, the level of global GDP would be 13% lower by 2050 (Chart 4).8

Chart 4: Global GDP impact of different decarbonisation scenarios

Source: NGFS Scenarios (Phase V).

The crystallisation of physical risks would be the main factor depressing economic activity in this scenario.

Economic losses deepen with time, as higher temperatures caused by a lack of mitigation efforts result in higher chronic physical risk.

Second, these estimates represent a stark increase from earlier assessments (Chart 5).

Chart 5: The estimated impact of climate change on economic activity has increased

Source: NGFS Scenarios.

This is due to updated estimates of the economic damage of climate change, especially on the persistent effects of rising temperatures and precipitation on the economy.

To be clear, there is uncertainty and debate around those estimates, as climate physical risk remains a highly complex field, but major improvements have been made recently.

Third, the macroeconomic costs of taking action to reduce greenhouse emissions are much smaller than the costs associated with inaction.

The NGFS has also provided a scenario consistent with an orderly and gradual transition to net zero by 2050 (Chart 4).

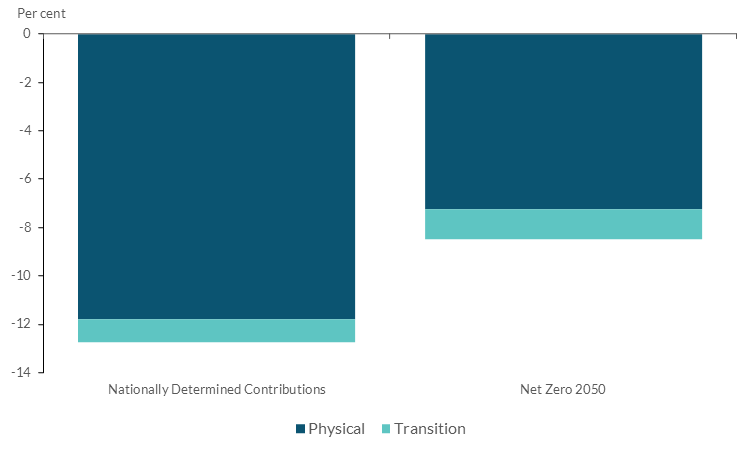

This still entails economic losses, because climate change still occurs under that scenario. And transition-related losses are also somewhat higher than under the NDC scenario (Chart 6).

Chart 6: The main impact on economic activity stems from physical risks

Source: NGFS Scenarios (Phase V).

But overall economic losses are smaller under an orderly and gradual transition. And the gap between overall economic losses in the two scenarios increases over time.

Put differently, the main conclusion around the relative costs of action versus inaction remains the same as in the Stern Review two decades ago, only starker.

Of course, there will be macroeconomic costs during the transition.

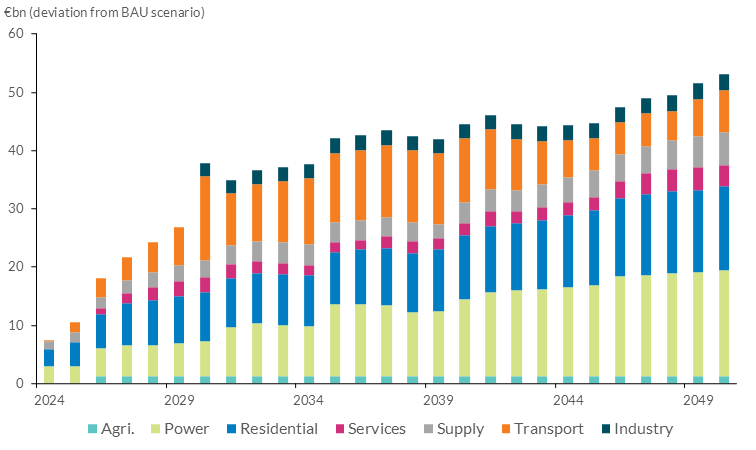

For Ireland, estimates suggest that additional investment of over €50bn is likely to be needed until 2050 to meet decarbonisation targets, most of it incurred over the next decade (Chart 7).9

Chart 7: The transition to climate neutrality will require additional investment

Source: Central Bank of Ireland, based on TIM model.

Work we have done with the Climate Change Advisory Council suggests that – in an economy with little spare capacity – undertaking those investments will require redirecting some scarce resources away from the tradeable sector of the economy.10

This would entail some macroeconomic costs throughout the course of the transition, although these are estimated to be relatively modest.

And, in the longer-run, especially given Ireland’s heavy dependence on imported fossil fuels, a transition to a climate-neutral economy will also entail long-term economic savings.

Ongoing analysis on options for recycling revenue from carbon taxes also indicates that there are policy choices that can reduce the costs, and enhance the benefits, of that transition.

This work forms the foundation for the economic advice we provide to the government around the macroeconomic trade-offs associated with Ireland’s transition to climate neutrality.

The exposure to rising physical risks requires adaptation investment

In addition to a macroeconomic lens, we have made progress in evaluating sectoral exposures to climate-related financial risks.

There are many different potential sources of physical risks for Ireland, but by far the main one stems from an increased likelihood of flooding, severe storms and rising sea levels.

So let me focus on that to illustrate the point.

As we have already seen, flooding can cause significant damage to property and infrastructure, leading to economic losses for households and businesses, as well as the financial system.

Climate science provides us with a quantification of the future risk of floods in Ireland.

The Office of Public Works’ (OPW) extensive nationwide analysis considers different future flood risk scenarios, with different combinations of rising sea levels and increases in rainfall.

But assessing financial risks requires translating these climate-related insights into potential economic losses.

To do that, my colleagues at the Central Bank have been working with the OPW to create a national dataset mapping every property in Ireland to current and future flood risks.

That can be used to estimate future damage costs and link properties to exposures of the financial sector.

This analysis helps us quantify the rising financial risks stemming from climate change.

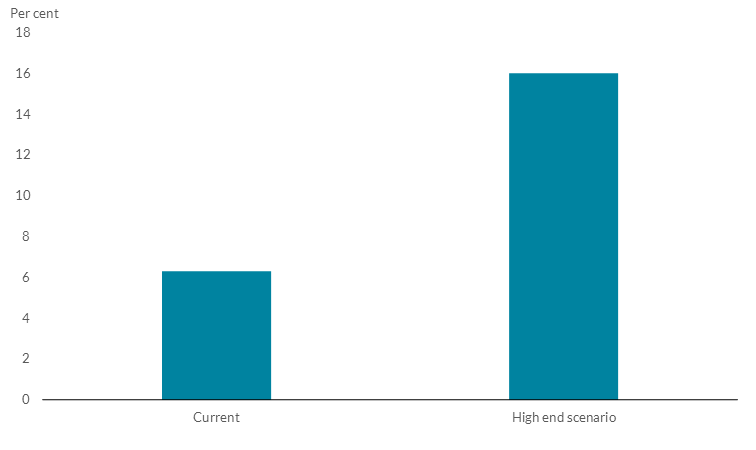

For example, we estimate that the share of the value of loans to businesses at risk of flooding would more than double under the OPW’s high-end scenario (Chart 8).11

Chart 8: The share of loans to companies at risk of flooding is estimated to more than double under the OPW’s high end scenario

Source: Ahangarkolaee et al (2025) ‘Measuring flood risk in business lending’, Behind the Data.

There are compounding factors to these direct effects.

First, the closer we get to that world, the higher the risk of underinsurance.

Separate work by the Central Bank on the flood protection gap has shown that approximately 1 in 20 buildings already face difficulties accessing flood insurance.12

And close to 90% of the economic cost of flooding relates to higher-risk buildings that have limited or no insurance access.

That’s where we are now. But, in the future, as flood risk worsens, so does the potential risk of uninsured losses.

Indeed, we estimate that the value of losses for those with limited access to insurance would increase by almost 50% under the OPW’s high-end scenario.

Second, our work on flood risk has also revealed how physical risks are already impacting credit conditions.

Forthcoming research suggests that loans to borrowers in flood-prone areas face higher interest rates and are more likely to be asked to post collateral for borrowing.

Third, there is evidence of a flood risk premium in the property market, suggesting that a higher risk of flooding would also affect asset valuations.13

Putting this all together – higher risk of damage, higher risk of underinsurance, impacts on credit conditions and impacts on valuations – it is clear that rising flood incidence due to climate change can increase the risk of economic losses for households and business.

Amongst others, these insights also speak to the importance of adaptation efforts.

Because the unfortunate reality is that the climate is changing, and will continue to change going forward, even if we were to accelerate mitigation efforts.

Surveys show that many Irish companies are concerned about the physical manifestations of climate change.14

But they themselves acknowledge they have not sufficiently invested in efforts to adapt to a changing climate.

Adaptation investment needs to increase, globally and in Ireland. Here too, the evidence suggests that early action is likely to be most effective in minimising long-run economic costs.15

The costs of inaction outweighing the costs of action is a recurring theme, including in the context of adaptation.

The Central Bank recently partnered with the Climate Change Advisory Council to understand the barriers to greater investment in adaptation in Ireland.

That work also considered a range of concrete actions that could increase adaptation investment, including strengthening awareness of local and sector-specific risks and improving estimates of the costs of adaptation nationally.

Management of climate-related risks by the financial sector has improved, but there is more to do

Precisely because of the macrofinancial effects of climate change I have described above, climate change also entails risks for the financial system.

In that context, a key supervisory priority of the Central Bank in recent years has been to strengthen the financial sector’s capabilities to manage climate-related financial risks.

And, over the past few years, we have seen meaningful progress in this area.

For example, we have seen improvements in governance around climate change and sustainable finance, in the approach to monitoring of climate-related risks, and in the deployment of scenario and stress testing analysis by regulated financial institutions.

That said, there is still more work to do to ensure that climate-related risks are integrated fully in risk management practices across the financial system.

For example, we still see inconsistencies across firms and sectors, data continues to be a challenge, and risk management practices are not applied consistently across all relevant portfolios and exposures.

So the effective management of climate-related financial risks across the financial system remains one of our key supervisory priorities, as outlined in our Supervisory and Risk Outlook report earlier this year. 16

We also recognise that climate change is a shared challenge and that collaboration can be a key enabler if we are to succeed collectively.

In that context, the Central Bank’s Climate Risk and Sustainable Finance Forum has provided a platform for stakeholders to work together to drive meaningful progress.

In recent years, for example, the Forum has helped bring together stakeholders from a range of sectors to share perspectives on best practices for the management of climate-related financial risks as well as on capacity building within regulated firms.17

More recently, the Forum has established a working group focusing on data and disclosures, a common challenge facing regulated firms across the financial system.

The Central Bank is ‘staying the course’

Let me conclude with some reflections on the Central Bank’s own journey around climate change.

I hope it is clear from the above why we have been increasingly focused on climate change in recent years.

Ultimately, it is because climate change poses risks to the economy and the financial system. And because the financial system has a key role to play in financing the transition to net zero.

So, understanding the macrofinancial effects of climate change and the transition to net zero is essential to allow us to take the appropriate actions needed to deliver our mandate.

Whether that is maintaining price and financial stability, providing economic policy advice to the Government, safeguarding the safety and soundness of individual firms, or protecting the interests of investors, including from the risk of greenwashing.

I am very conscious that shifting policy priorities globally are leading to a weakening of commitments to climate change mitigation in some parts of the world.

Sometimes I get asked whether that shifting geopolitical environment means we are reducing our own focus on climate change.

The simple answer to that is no. We are staying the course.

Our focus is – and has always been – on delivering our mandate, and we have been approaching climate change through that lens.

If anything, further delays in climate change mitigation would mean that the macrofinancial risks from climate change would become more pressing.

Thank you for listening.

[1] I am very grateful to James Carroll, Patrick Haran, Niall McInerney and Rory McElligott for their advice in preparing these remarks.

[4] Dr. Jane Goodall’s 2025 Earth Day Message.

[5] ‘Emission Gap Report 2025’, United Nations Environment Programme, November 2025.

[6] ‘Ireland’s Provisional Greenhouse Gas Emission’, Environmental Protection Agency, July 2025.

[7] ‘Cross-sectoral Review: Annual Review 2025’, Climate Change Advisory Council, November 2025.

[8] NGFS Scenarios Portal https://www.ngfs.net/ngfs-scenarios-portal.

[9] See Conefrey et al (2024), ‘Fiscal Priorities in the Short and Medium Term’, Central Bank of Ireland, Quarterly Bulletin, 2024 Q2.

[13] For Irish evidence and the housing market, see Gillespie et at (2025) ‘Estimating the flood risk premium: evidence from a once-off informational shock’, Environmental and Resource Economics, Vol. 88. For UK evidence, see Skouralis et al (2024) ‘Does flood risk affect property prices? Evidence from a property-level flood score’, Journal of Housing Economics, Vol. 66.