Vasileios Madouros, Deputy Governor speech at Dublin Economics Workshop

19 September 2025

Speech

The Macroprudential Mortgage Measures Ten Years on: Taking Stock1

Cantillon Lecture, at the 48th Dublin Economics Workshop

Twenty years ago, Ireland was in the midst of an unsustainable, credit-driven property boom, rooted in weak lending standards. Those shaky macro-financial foundations, amplified by underlying fiscal vulnerabilities, eventually led to Ireland’s financial and subsequent economic crisis. Ten years ago, as the economy was recovering from that crisis, the Central Bank introduced new macroprudential measures to guard against the risk of such an episode reoccurring. Or, as Governor Patrick Honohan put it at the time, to “protect the new generation [that is] establishing households – and the nation at large, from the risk of a repetition of what happened before”.2

The introduction of the measures did not happen in a vacuum. At an international level, the global financial crisis led to widespread reforms to the regulatory architecture, from stronger prudential standards to an enhanced approach to supervision. The post-crisis financial architecture also saw the introduction of a new policy framework altogether: macroprudential policy. This entailed a shift in thinking, by explicitly taking a system-wide lens on resilience and focusing on the interaction between finance and the broader economy.3 The mortgage measures were Ireland’s first macroprudential intervention. Indeed, back in 2015, we were amongst the first European adopters of mortgage market interventions with an explicit macroprudential objective. A decade on, these are now well established tools at a global level.

The measures have not been without debate. When they were first proposed, the Central Bank received the highest number of responses to any of our consultations, surfacing a range of strongly-held views amongst the public. This is not surprising. The measures affect people very directly. Buying a house is the most important financial decision that most people will make in their lives. And mortgages are the largest form of borrowing by households. So the measures matter for individuals, and they matter for the economy as a whole. Indeed, I would characterise the measures as being amongst the most important public policy interventions introduced by the Central Bank, both from a macro-stabilisation perspective and from a consumer protection perspective.

In that context, now that we have a decade of experience with the mortgage measures in place, I wanted to take this opportunity to take stock of the lessons we have learned over the past decade. How have the measures fared over that period? What have we learned about how they affect the economy, and where do we need to make further progress? And what lies ahead?

The why and the how

But let me start with what a brief reminder of the why and the how of the measures.

On the why, put simply, they aim to ensure that lending standards in the mortgage market remain sustainable over time. In doing so, they support the resilience of borrowers, lenders and the broader economy. And they seek to prevent the emergence of an adverse and unsustainable feedback loop between credit and house prices.4

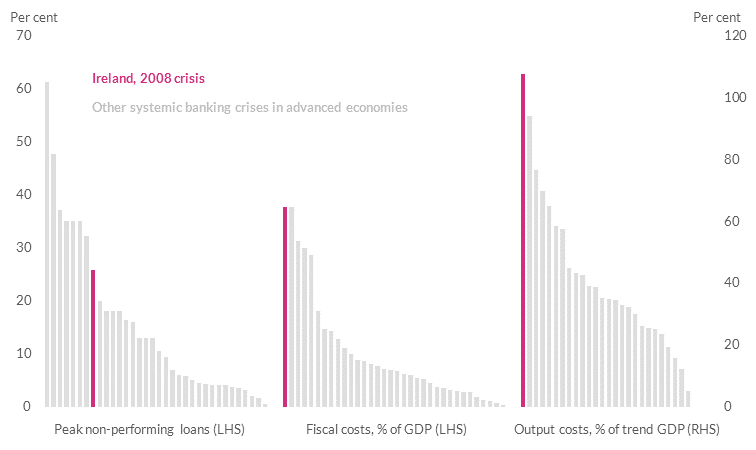

These can come across as somewhat abstract concepts. But, as we learned in a very painful way in Ireland – the damage of not achieving these objectives is anything but abstract. The costs of the financial crisis on society were very large. These costs were clearly felt by the large number of mortgagors that were over-indebted and found themselves in financial distress. But they were also felt by those not in the mortgage market, because the financial crisis morphed into an economic crisis, affecting everyone in the country. And some of these costs have been persistent. For example, the long-lasting scars of the crisis on the construction sector are still weighing on housing supply today, with significant adverse effects on younger generations. On different metrics, the Irish financial crisis was amongst the most costly, even compared against systemic crises in other advanced economies (Chart 1). And, of course, behind all these numbers are people, for whom the damage of the financial crisis was deeply personal.

Chart 1: The costs of the Irish financial crisis were very large, even compared to other systemic crises in advanced economies

Source: Laeven and Valencia (2020), ‘Systemic Banking Crises Database II’. IMF Econ Rev 68, 307–361.

This broad lens is important in terms of how we think about the objectives of the measures. Unlike what I sometimes hear, the measures, like all our regulatory interventions, are not there to ‘protect the banks’. They are there to guard against the damaging effects of unsustainable mortgage lending on society as a whole, now and into the future.

On the how, the measures effectively constrain the share of new mortgages that lenders can extend at higher levels of indebtedness. But let me highlight three elements of their design in particular.

- First, there are two limits: one based on the size of the loan relative to borrowers’ income (LTI) and one relative to the value of the property (LTV). These have different, but complementary, aims. The LTI limit acts as a long-term anchor between developments in the mortgage market and household incomes and supports mortgage affordability, while the LTV limit provides a buffer against house price falls and the risk of negative equity.

- Second, the measures are not designed to act as hard caps. The framework incorporates so-called ‘allowances’, meaning that lenders can extend a share of new lending above the limits. These allowances are important and provide flexibility for individual circumstances to be taken into account by lenders. Because, ultimately, the measures are not there to replace lenders’ own responsible lending standards, they are there to act as system-wide guardrails.

- Third, there is a differential treatment by borrower type. The evidence is clear that, other things equal, first-time buyers (FTBs) have had a lower default propensity than second and subsequent buyers (SSBs).5 The role of SSBs in housing market dynamics is also very different: as they already own a home, in an environment of rising house prices, they have additional resources available for future purchases and, therefore, a greater propensity to amplify cycles.6 So the LTI limit is set at 4 times income for FTBs, and 3.5 times income for SSBs.

The design of the measures has been tailored to the structure of the Irish mortgage and housing markets. And, importantly, that design has evolved since their introduction in 2015, as we have learned more about their operational effectiveness over time, a theme that I’ll come back to later.

How have the measures delivered against their objectives over the past decade?

So what have we learned about the effectiveness of the mortgage measures in achieving their objectives over the past decade? Analytically, this is not an easy question to answer with precision. The macro-financial benefits of the measures are not directly observable: indeed, they stem from the absence of things, such as unsustainable booms and busts, over-indebtedness or the emergence of widespread financial distress. The benefits of the measures are also long-term in nature: they may not be immediately obvious today, but they can become more evident in times of stress.

What we do know is that the broader environment in which the measures have been operating over the past decade has been testing – and, in the second half of the decade, shock-prone. For much of the period, the process of post-crisis balance sheet repair by both banks and households was still ongoing. In the housing market, we have had a persistent shortage of supply relative to demand, putting upward pressure on the cost of places to live, whether to buy or to rent. Halfway through the decade we saw the onset of a global pandemic, followed by the energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, very high inflation and sharply rising interest rates.

So what have we learned about the effectiveness of the measures in that environment?7

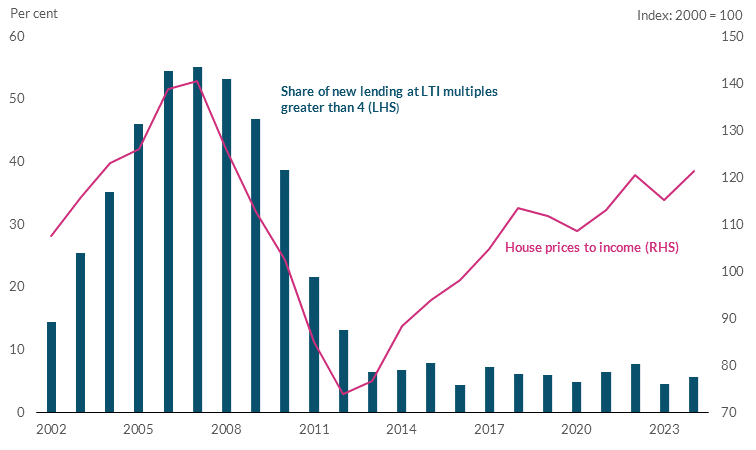

Let me start with resilience. An environment of rising house prices relative to incomes could have created the conditions for a ramp-up in highly-indebted households. Indeed, that was precisely the pattern in the last housing cycle in the 2000s (Chart 2). And we know that it is highly-indebted households that are both most vulnerable to default, and also more likely to cut spending in a downturn, amplifying economic stresses.8 The measures have guarded against such dynamics. Indeed, unlike the last cycle, the increase in house prices has not led to a sharp increase in highly-indebted mortgagors. Mortgage credit has been flowing to the economy in aggregate, but the measures have constrained the emergence of a tail of highly-indebted households.

Chart 2: Unlike the last cycle, rising house prices relative to incomes have not led to an increase in highly-indebted borrowers

Source: Central Bank of Ireland and CSO.

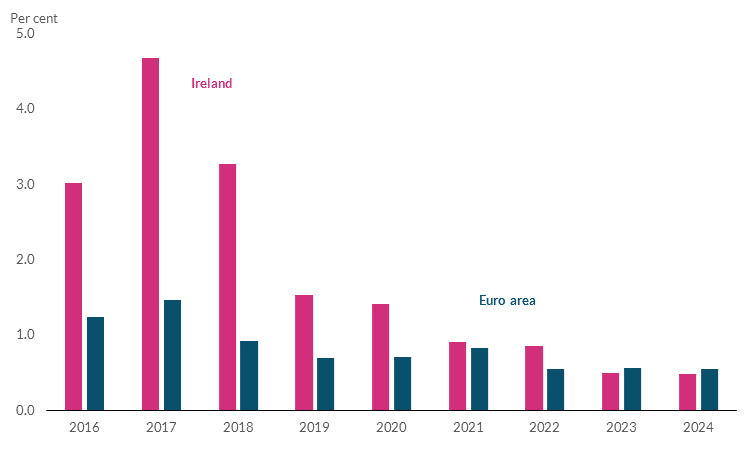

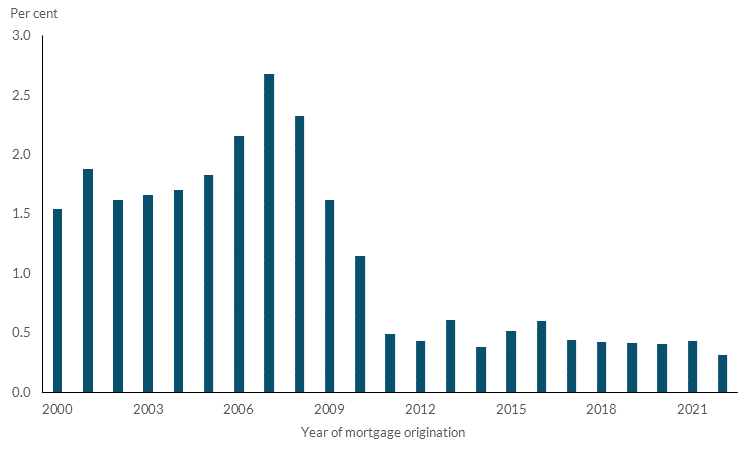

In turn, these more sustainable lending standards have contributed to lower levels of financial distress amongst mortgagors. For a prolonged period, Ireland had much higher levels of new mortgage defaults than the rest of the EU. Even as late as 2019, when the economy had recovered and unemployment was low, new mortgage defaults in Ireland were double the EU average. That gap has now closed, pointing to greater underlying resilience of borrowers (Chart 3). And, if one looks deeper, where we have seen evidence of distress, whether it is those that opted for payment breaks at the start of the pandemic, or those borrowers that did flow into default in the more recent episode of high inflation and rising interest rates, that distress has predominantly manifested in mortgages issued before the financial crisis, at much weaker lending standards (Chart 4).9 Of course, there are limits to how much we can infer from this. Government interventions supported households in response to the big shocks of the past decade – whether the pandemic or the cost of living crisis. But the evidence points to a strengthening of underlying resilience of borrowers and lenders.

Chart 3: New flows into mortgage default in Ireland have converged to the euro area average over the past decade

Source: EBA Risk Dashboard

Note: EU average consists of AT, BE EE,FI,FR,DE,IE,LT,LU,NL, PT, ES & IT.

Chart 4: Mortgages that defaulted over 2023-2024 were predominantly issued at weaker lending standards before the financial crisis

Source: Central Bank of Ireland.

While the mortgage measures have strengthened resilience of new borrowers, the long shadow of past unsustainable lending practices remains, as evident by the cohort of borrowers on long-term mortgage arrears. While we have seen a marked reduction in the number of mortgage accounts in long-term arrears in recent years, there is still more to be done. So we remain focused on arrears resolution. We have continuously challenged regulated entities to do more to support borrowers experiencing financial difficulty, and particularly those in long-term mortgage arrears. When a borrower is in, or facing arrears, our expectation is that regulated entities provide appropriate and sustainable solutions and engage with broader, system-wide solutions, such as mortgage-to-rent or personal insolvency arrangements. And, as part of our modernised Consumer Protection Code, which comes into effect early next year, we have incorporated important amendments to strengthen the Code of Conduct on Mortgage Arrears.

What about the impact of the measures on guarding against an adverse feedback look between credit and house prices? Of course, and I need to be very clear on that, the mortgage measures do not, and indeed cannot, target house prices. House prices are affected by a range of factors, most fundamentally the balance between the underlying demand for, and supply of, housing in the economy. What the mortgage measures do seek to achieve is guard against an unsustainable relationship between credit and house prices from emerging, similar to what we saw in the 2000s. That is a subtle distinction, but an important one.

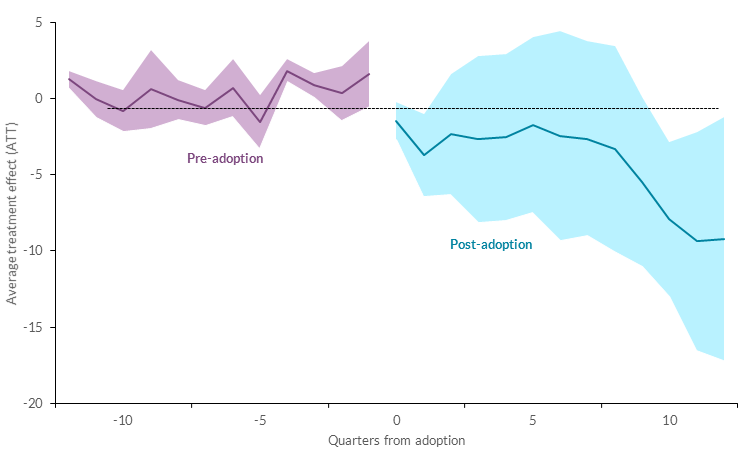

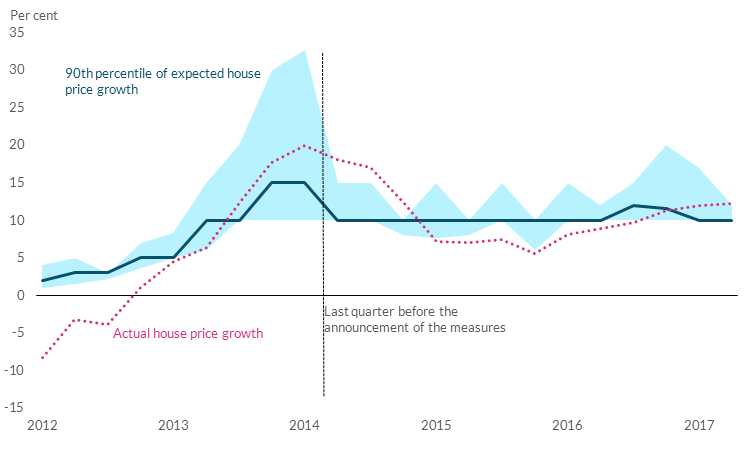

Again, analytically, it is not easy to gauge with precision what might have happened in the absence of the measures. Still, there now is a body of evidence that macroprudential measures in the mortgage market reduce house price growth relative to what might otherwise have been the case (Chart 5).10 The measures can also reduce the tail of expectations of future house price increases, which can act as an important amplification mechanism, if market participants borrow on the expectation of rapidly rising house prices in the future. Indeed, in Ireland, we did see a meaningful reduction in the tail of house price expectations upon the introduction of the measures (Chart 6).

Chart 5: Cross-country evidence suggests that the introduction of mortgage measures lowers house prices growth

Source: Morretti and Riva (2025). Note: Treatment variable is the introduction of borrower-based measures in a given country (LTV or income-based limits). Outcome variable is the growth in the house price index. Shaded areas report 90% confidence intervals.

Chart 6: The tail of positive house price growth expectations in Ireland fell after the introduction of the mortgage measures

Source: McCann and Riva (forthcoming).

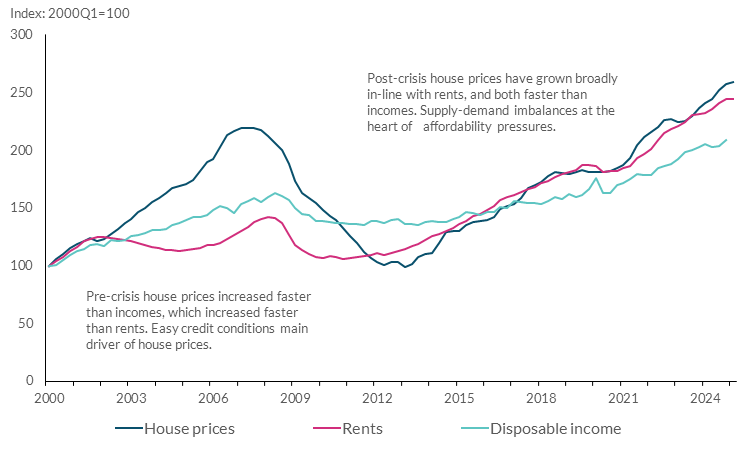

Of course, over the past decade, we have seen continued increases in house prices relative to incomes in Ireland. This begs the question as to the drivers of those house price developments.

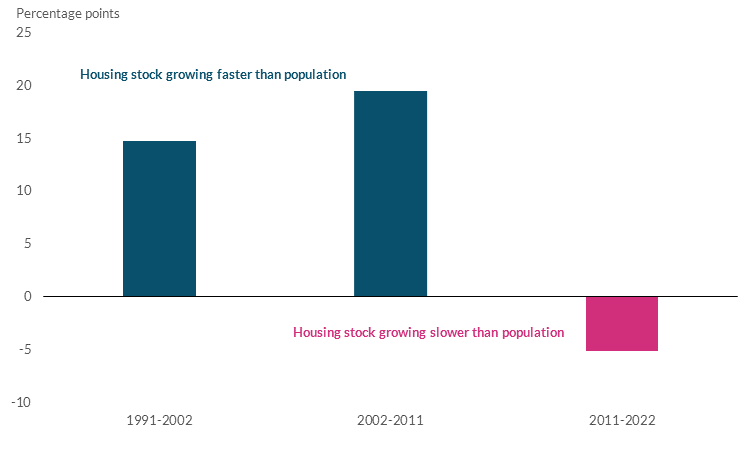

For me, a good diagnostic is the relationship between house prices and rents: effectively the rental yield. In the period before the financial crisis, house prices increased much faster than rents, leading to a compression in the rental yield. That is consistent with loose credit conditions playing a key role in driving house prices. Over the past decade, however, rents and house prices have both increased significantly, and both have risen faster than incomes (Chart 7). The rental yield has been broadly stable. That is consistent with the underlying factor driving house prices (and rents) being the imbalance between demand and supply for housing (Chart 8). Put differently, while the symptom of high house prices is evident in both the cycle of the 2000s and the current cycle, the underlying diagnosis is very different. And, what we have not had, is unsustainable lending standards further amplifying these house price dynamics.

Chart 7: The relationship between rents and house prices is very different to the last cycle, pointing to supply-demand imbalances as the main driver of house prices

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland calculations.

Chart 8: Growth in the total housing stock has not kept up with the increase in Ireland’s population over the past decade

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland calculations.

Pulling this all together, the measures have played an important role in strengthening resilience of borrowers, lenders and the broader economy over the past decade. They have also guarded against the emergence of an adverse feedback loop between house prices and credit that we might have seen, had unsustainable lending practices emerged. These are substantial macro-financial benefits, especially in the environment of heightened economic volatility that we have been experiencing.

Weighing benefits and costs

Of course, as policymakers, we do not aim for resilience at any cost. That would not serve society well. Like all policy interventions, the mortgage measures entail both benefits and costs from the perspective of the economy as a whole. Our job is to balance these.

Conceptually, the mortgage measures can entail economy-wide costs through different channels.11 For example, they can weigh on aggregate consumption through the required increase in savings by prospective homeowners to access mortgage finance or through the impact of the measures on house prices and, therefore, household wealth. There are also potential channels to business activity too. For example, small businesses often post residential property as collateral to access finance. So, by dampening house price growth, macroprudential measures can weigh on business borrowing and activity. Beyond those aggregate effects, we are very conscious that the measures have particular effects on certain segments of the population, especially some potential first-time buyers.12

It was precisely because of the balance between benefits and costs, which we continuously aim to strike, that we recalibrated the measures in 2022, with a focus on first-time buyers. This was an important, and difficult, decision by the Central Bank, so let me elaborate briefly on the reasons.

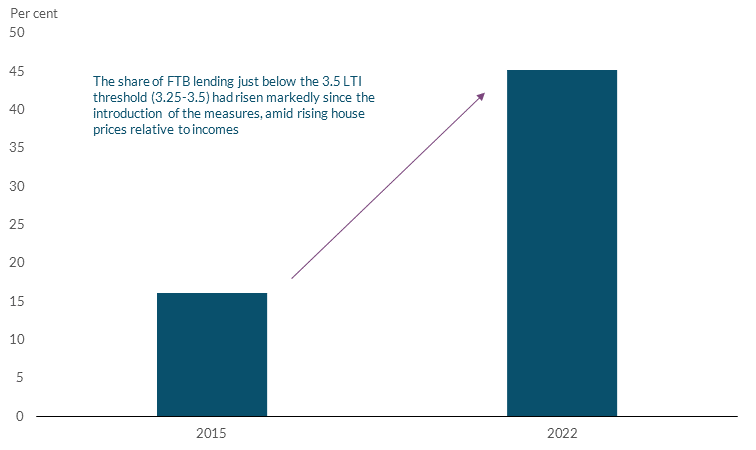

The mortgage measures, and especially the LTI limit, had become increasingly binding over time, particularly for first-time buyers, amid the continued growth in house prices relative to incomes (Chart 9). Now, if house prices are rising faster than incomes because of weakening lending standards or unsustainable credit dynamics, the fact that the measures are becoming more binding is a feature, not a bug: they are doing their job. But if house prices are rising faster than incomes due to structural factors – for example, underlying shifts in the supply of housing – that can affect the cost-benefit calculus of the calibration of the measures.

Chart 9: Amid rising house prices relative to incomes, the measures had become very binding for first-time buyers

Source: Central Bank of Ireland.

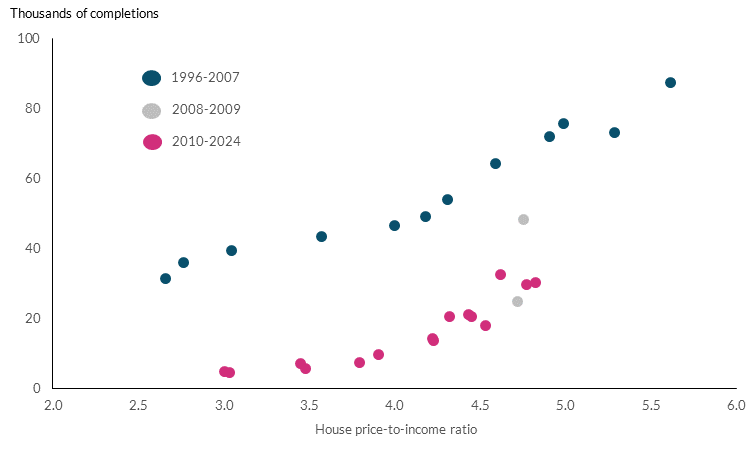

In our analysis, part of the increase in house prices relative to incomes since the introduction of the measures had been due to structural factors. The recovery in housing supply had been slower than we had expected upon the introduction of the measures. Indeed, a more persistent pattern was becoming apparent, with fewer homes being built, for a given level of house prices relative to incomes, compared to the past (Chart 10), implying a gradually increasing cost of the measures.

Chart 10: Since the financial crisis, fewer houses are being built, for a given level of house prices relative to incomes

Source: CSO, PTSB/ESRI, Central Bank of Ireland calculations.

Note: Completions prior to 2011 have been obtained by taking total estimates of (ESB) electricity connections and removing average number of connections in each year that are unrelated to dwelling completions.

The flexibility embedded in the measures through the allowances meant that the framework had been able to mitigate the effects of these slow-moving changes over time. But we also wanted to ensure the measures were fit for the future. In that context, and given a broader strengthening of resilience of borrowers and lenders over the same period, we judged that we had some policy space to ease some of the costs of the measures, without disproportionally eroding their benefits. So we increased the LTI limit for FTBs from 3.5 to 4 times incomes, partly offset by a reduction in the allowances at the same time. We also made some other important adjustments, such as simplifying the framework for allowances and switching the differential between borrower types from the LTV limit to the LTI limit. These all reflected lessons learned over time around the operational effectiveness of the measures.

As you would expect, we have been evaluating carefully the impact of these targeted adjustments. For example, some of the research we have conducted on the borrower-level impact of the changes points to some easing of costs through an increased probability of first-time buyers buying a newly-built property as well as greater access to mortgage finance by younger households.13 At the same time, the analysis also points to certain borrowers in Dublin purchasing more expensive homes following the recalibration, without that necessarily being explained by the quality characteristics. And while those borrowers account for around 2.5% of total market activity, this highlights some of the very real trade-offs that we face in considering the calibration of the measures.

As I mentioned, that was not an easy decision for the Central Bank. Ultimately, though, it was a manifestation of the fact that we always seek to weigh the benefits and costs of our interventions, based on evidence, from the perspective of the public good.

Deepening our understanding – priority areas

While we have learned a lot over the past decade, both from our own experience and the experience of others, deepening our understanding of the impact of the measures is a continuous process. From a policymaker’s perspective, I wanted to highlight two priority areas in particular.

The first relates to the analytical framework for weighing the costs and benefits of the measures. This applies to macroprudential policy overall, given that is still a relative ‘young’ discipline. By comparison, though, over the past 15 years, we have made substantial progress in developing a framework for assessing the benefits and costs of different levels of bank capital.14 For interventions like the mortgage measures, no such widely-accepted analytical framework exists globally.

At the Central Bank, we have been building our capabilities in this area in recent years. For example, we have augmented some of our macroeconomic models to incorporate transmission channels for the mortgage measures, allowing us to better assess the trade-offs.15 We have also conducted research that seeks to compare the costs of the measures in terms of economic activity in the central case with the benefits in terms of reducing volatility of output.16 These are good starting points, though I would say that, at this stage, they are still nascent attempts to get us towards a comprehensive framework for weighing benefits and costs.

There are also important conceptual questions that we need to tackle to make progress in this area. For example, most of the macroeconomic costs of the mortgage measures operate on the demand side of the economy, so should not have a permanent effect on the level of output. By contrast, the costs of financial crises are persistent, with some studies pointing to permanently negative effects on the size of the economy.17 Another example is that the benefits of the measures stem from making low probability events less damaging, a bit like an insurance payout. Whereas the costs of the measures are there in central expectation, similar to the premium on insurance. Unlike (most) insurable events, though, we cannot have a firm grip on the probabilities of these tail events, given how infrequent financial crises are.

The second area that I would highlight as important to focus our analytical efforts on is the interaction between the mortgage measures and different aspects of the broader housing market.

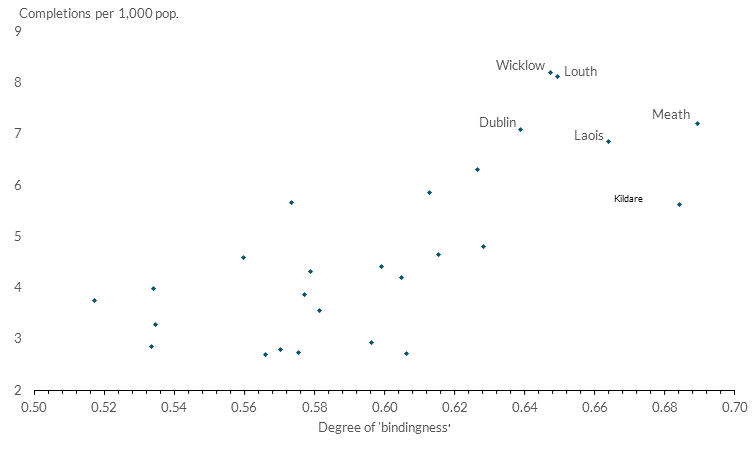

One important dimension is the interaction between the mortgage measures and housing supply. And, specifically, whether the measures affect how responsive supply is to house prices. We know that parts of the country where the mortgage measures have been most ‘binding’, because of higher house prices relative to incomes – are also the parts of the country where we have seen the biggest increase in housing supply (Chart 11). On the face of it, at least, this would suggest that housing supply has been responding to price signals. But this has also been explored more formally, with research suggesting that, accounting for constructions costs, there had been no change in the responsiveness of supply to house prices since the measures were introduced.18 Put differently, lower levels of housing supply than in the past can be explained by the rising cost of construction over time, rather than a lower sensitivity to house prices.

Chart 11: Housing supply has been responding to price signals, despite the measures being more binding

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland. Note: Completions per 1,000 pop. = units completed / 1000's of population (per county). Population data based on CSO annual population estimates.

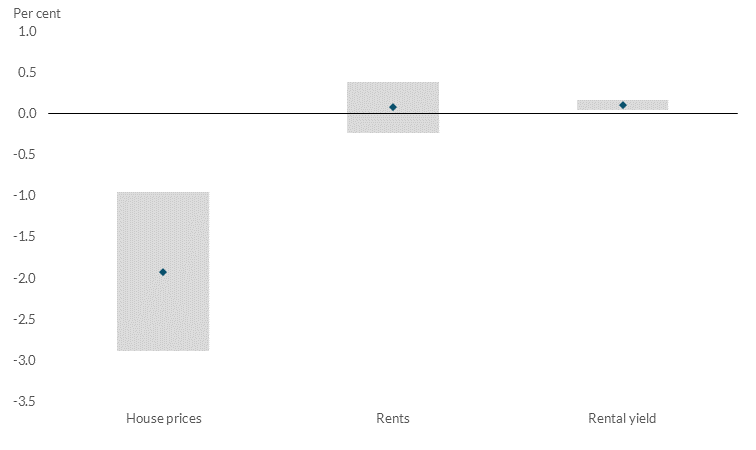

Another important dimension is the interaction between the mortgage measures and the rental market. Instinctively, it is natural to think that looser mortgage credit conditions might mean less pressure on the rental market, as more people are owner-occupiers. But, all else equal, more households in owner-occupation can also mean a smaller stock of rental properties available to remaining renters, with an unclear effects on rents. Ultimately, this is an empirical question – but the evidence remains sparse and mixed. Some of our own analysis has found that the introduction of the measures was associated with a modest increase in rental yields in the short term, albeit driven mainly by reduced house price growth, rather than higher rental growth (Chart 12).19 But other studies find a bigger effect of mortgage restrictions on rental growth and also highlight potential dependencies with other aspects of the rental market, such as the presence of institutional investors.20

Chart 12: Estimated impact of the introduction of the mortgage measures on rents and house prices

Source: Yao et al (2025)

Overall, while we have learned a lot over the past decade, there is still further to go. I do not want this to come across as of academic interest. These questions matter for policy, and, therefore, they matter for the public that we serve. Ultimately, evidence-based policy is part of our DNA at the Central Bank. So it is a priority for us to continue to deepen our understanding of the effects of the measures, like all our policy interventions.

Looking ahead

Let me finish off by looking ahead. Of course, especially in light of the current levels of geoeconomic uncertainty globally, it can seem a fool’s errand to make statements about the future with much confidence. But, if I take a step back, my own judgement is that – over the course of the next decade, the environment in which the mortgage measures will operate may well be more challenging than the one that prevailed over the past decade. There’s three reasons for that.

First, the financial crisis is now increasingly in the rear view mirror for many. From a political economy perspective, internationally, there is increasing focus on the ability of the financial system to support growth, which risks manifesting as a pro-cyclical turn of the global regulatory cycle. From the perspective of the financial system, the process of post-crisis balance sheet repair is now largely complete and there is greater focus on growth and expansion. From the perspective of the public, naturally, attention is on today’s challenges – including around housing affordability – rather than concerns about the costs of financial crises of the past.

Second, domestically, there is, rightly, growing focus on policy measures to increase housing supply.21 This means that, over the next decade, we are likely to see higher housing market transactions – and, in turn, an associated increase in mortgage market activity. With house prices already elevated relative to household incomes, this combination of factors has the potential to create the conditions for rising indebtedness across the household sector, especially if lending standards in the mortgage market were to weaken.

Finally, from a broader macroeconomic lens, we are facing a number of ongoing structural shifts, related to geopolitics, fragmentation of the global economy, artificial intelligence, demographics and the increasing frequency of extreme weather events due to climate change. These suggest that the environment for economic activity and inflation (and, therefore, also interest rates) will remain highly uncertain and, indeed, potentially more volatile. Put differently, we are facing a world with the potential for more frequent and larger supply-side shocks, which could test the financial position of households.

It is precisely in such a more challenging environment that the benefits of the measures are also likely to be higher. So how do we ensure that they continue to do their job over the next decade? Let me cover three dimensions guiding our approach.

First, we will continue to evaluate the measures on an ongoing basis, as we have done to date. If you look at the mortgage measures now, and compare them to when they were first introduced a decade ago, they have not been static. There have been adjustments to their design, to their calibration and to our overall policy strategy.22 This is important. To remain fit for purpose over time, all policy frameworks need to be able to evolve, amid broader structural changes in the economy and the financial system. And the fact that we have made adjustments is indicative that we are – and will remain – responsive to those changes, where justified by evidence.

Second, we will continue to deepen our understanding of the benefits and the costs of the measures. To do so, we will not just rely on our own analysis. We also want to engage with external researchers, to benefit from broader perspectives and expertise. More broadly, as I mentioned upfront, when we first introduced the measures, we were amongst a very small number of European countries to have explicit macroprudential measures in the mortgage market. Now, these are a widely employed tool by macroprudential authorities across Europe, so we can also learn from others’ experience.

Third, throughout, we will place particular emphasis on engagement, transparency and accountability. This is relevant to all our policy interventions, but it is especially important for interventions like the mortgage measures, which affect people very directly. Actively engaging with, and listening to, a broad range of stakeholders, and being transparent about our judgements and the rationale behind them, are essential foundations for accountability. This is the approach we have taken over the past decade – and our commitment to openness and transparency will remain steadfast into the future. Indeed, that will become even more important if the operating environment does become more challenging over the next decade.

Conclusion

Let me conclude. I am very conscious that I have spoken about the mortgage and housing markets from a macro-financial lens. But there is a critical societal dimension to the very real challenges people are facing in accessing affordable housing – whether to rent or to buy. At its core, that affordability challenge stems from the imbalance between housing supply and demand. Rightly, therefore, the core focus of public policy is on measures to boost housing supply. As that happens, it is important that dynamics in the mortgage market, which ultimately underpins housing activity, remain sustainable. That is the role of the mortgage measures.

Over the course of the past decade, the measures have become increasingly accepted by the public that we serve in Ireland. This is an important foundation, because – looking ahead to the next decade – the environment in which the measures operate may well become more challenging. But that is also when the value of these interventions will be higher. Our focus will be on ensuring that the measures continue doing their job, always weighing their benefits and costs, from the perspective of the public good.

Thank you for your attention.

[1] I am very grateful to Mark Cassidy, Edward Gaffney, Niamh Hallissey, Patrick Haran, Conor Kavanagh, Gerard Kennedy, Eoin O’Brien, Cian O’Neill, and Maria Woods for their advice and suggestions in preparing these remarks.

[8] For Irish evidence on highly indebted households and default risk, see Lydon and McCarthy (2011) ‘What Lies Beneath? Understanding Recent Trends in Irish Mortgage Arrears’, Central Bank of Ireland, Research Technical Paper, 2011, No. 14 (PDF 618.5KB), and McCarthy (2014) ‘Dis-entangling the mortgage arrears crisis: The role of the labour market, income volatility and housing equity’, Central Bank of Ireland Research Technical Paper, 2014, No. 2 (PDF 476.15KB). For Irish evidence on highly-indebted households and spending, see Le Blanc and Lydon (2019) ‘Indebtedness and spending: What happens when the music stops? (PDF 3.6MB), Central Bank of Ireland, Research Technical Paper, 2020, No. 14, and Fasianos and Lydon (2021) ‘Do households with debt cut back their consumption more in response to shocks? Central Bank of Ireland, Research Technical Paper, 2021, No. 14. (PDF 2.35MB)

[10] For Ireland, see, for example, Kelly et al (2018) ‘Credit conditions, macroprudential policy and house prices’, Journal of Housing Economics, Vol 41, and Acharya et al (2022) ‘The anatomy of the transmission of macroprudential policies’, Journal of Finance, Vol. 77, Issue 5. For international evidence, see Richter et al (2019), ‘The cost of macroprudential policy’ Journal of International Economics, Vol. 118, Pogoshyan (2019) ‘How effective is macroprudential policy? Evidence from lending restriction measures in EU countries’, IMF Working Paper, WP/19/45, and Moretti and Riva (2025) ‘The impact of borrower-based measures: an international comparison’ Central Bank of Ireland, Staff Insights.