Key Insights

The rental yield is an important metric for gauging sustainability of the housing market. This Insight studied the impact of the mortgage measures on rental yields across Irish counties in the two years following introduction in 2015.

We find that there are clear and strong effects on house prices, which drive up the rental yield across counties, but find only a small and imprecise direct impact on rents.

Multiple factors are likely at play in explaining the muted response of rents, including changed house purchase behaviour and increased supply by institutional investors over the estimation period.

Introduction

Mortgage measures in Ireland

This Insight examines the impact of the mortgage measures (“the measures” hereafter), introduced by the Central Bank of Ireland (the "Central Bank") in 2015, on the Irish rental market. The measures promote financial stability by fostering prudent lending standards and aiming to prevent an unsustainable link between credit and house prices. However, they may also affect the rental market by restricting access to mortgage credit, thereby increasing demand for rental housing. Our analysis seeks to provide a deeper understanding of the impacts the measures have had on the rental market.

The measures were introduced during a period of growing imbalances in the housing market, with prices rising by approximately 15 per cent nationally and 25 per cent in Dublin in 2013, primarily due to supply shortages (CBI, 2014 (PDF 1.43MB)). The objective was to ensure that the post-crisis housing market recovery would not be destabilised by a renewed, credit-driven price cycle, thereby strengthening resilience against future economic or financial downturns.

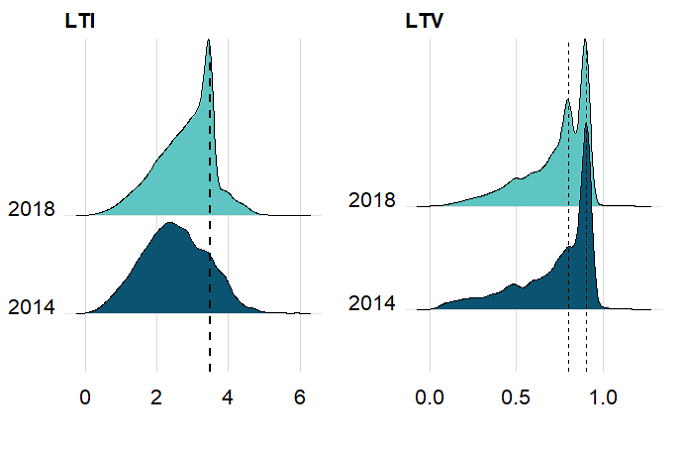

In 2015, the Central Bank introduced caps on Loan-to-Income (LTI) and Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratios for new mortgage lending. The LTI limit was set at 3.5 times income for all new borrowers, while a sliding LTV limit (starting from 90 per cent) was set for first-time buyers (FTBs) and an LTV limit of 80 per cent was set for second and subsequent buyers (SSBs) (Figure 1). A share of new lending was allowed above the limits, known as allowances, up to 20 per cent in the case of the 3.5 times LTI limit on introduction. In 2014, the year before implementation, around 40 per cent of new mortgages were above the 3.5 times LTI limit and above a 90 / 80 per cent limit for FTBs / SSBs, although a proportion of this lending would still have been possible under the limits given the flexibility allowed in the framework. In subsequent years, lending shifted and clustered around the limits. By 2018, more than 20 per cent of new mortgage lending was at the LTI cap of 3.5, and between 25 and 45 per cent was at the respective LTV caps. This bunching indicates that the measures became binding constraints for many borrowers.

Measures became binding constraints for many borrowers

Figure 1: Distribution of LTI and LTV before and after the measures

Source: Monitoring Template Data, Central Bank of Ireland

Note: These figures plot the distribution of LTI and LTV of new mortgages at their origination in 2014 and 2018. Dashed lines represent LTI limit for FTBs at 3.5 without the sliding limit for FTBs and allowances at 0.9 and SSBs at 0.8.

Accessibility: As it is not possible to make the CSV for this chart available, the following alternative text is provided: In the chart, we use a Ridgeline plot (sometimes called a Joyplot) to show the shifts in the distribution of LTI/LTV before and after the introduction of mortgage measures. These plots are based on the whole set of individual data (approx. 50 thousand data points) directly from confidential datasets - Loan-level data and Monitory template data - of the Central Bank of Ireland. They show that, in 2014, almost 40 per cent of new mortgages were above the 3.5 times LTI limit and above a 90 / 80 per cent limit for FTBs / SSBs. By 2018, the distribution of new lending had shifted and clustered around the policy limits. This bunching indicates that the measures became binding constraints for many borrowers.

While extensive research confirms the measures’ effectiveness in limiting the pro-cyclicality of house prices, credit and leverage (e.g., Acharya et al., 2022; IMF, 2014), further understanding the spill-over effects of these types of measures onto the rental market is warranted (see discussion in Abreu et al., 2024, among others). This Insight aims to contribute to this topic by examining how introducing borrower-based measures impacted rental yields in Ireland.

The role of rental yields and theoretical underpinnings

We focus on the rental yield because it provides a key measure of rental market pressure and housing affordability. Defined as the ratio of annual rents to housing value, rental yields capture the relative cost of housing services between owning and renting. An increase in rental yields implies that renting becomes a more expensive form of accessing housing services compared with homeownership.

Theoretical models suggest that tighter policies such as borrower-based measures can raise rental yields by shifting demand from ownership to renting, thereby increasing pressure on rental yields, ceteris paribus. The mechanism operates as follows: when stricter mortgage measures prevent some buyers from obtaining sufficient credit to purchase homes, these prospective buyers remain in the rental market for longer. Consequently, it leads to the shift in demand for housing services from the owner-occupier market to the rental market. In equilibrium, the additional demand must be matched by increased rental supply. To attract new investors to enter the market, rental yields must rise.

Post-Crash Rental Market Dynamics and Policy

Housing/rental price developments since 2010

Ireland’s rental market experienced significant shifts between 2010 and 2019, beginning with a sharp decline in rents following the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and followed by a prolonged period of rapid growth. During this upswing, rental affordability deteriorated due to overlapping policy interventions and persistent structural supply shortages.

The decade opened with steep rent declines in the aftermath of the GFC. By 2011, the average national rent had fallen to €825 per month—a substantial reduction from €1,100 per month in early 2008. This downturn was driven by economic turmoil and a temporary oversupply of housing. However, by 2012 the market had pivoted sharply. Supported by post-crisis economic stabilisation and an emerging housing shortage, rents entered a sustained upward trajectory that accelerated from late 2014 onwards. By the end of 2019, the average national rent had reached €1,402 per month, nearly double its 2011 level. Dublin led this growth, with average rents rising to around €2,000 per month (Daft.ie Rental Report, 2019 Q4).

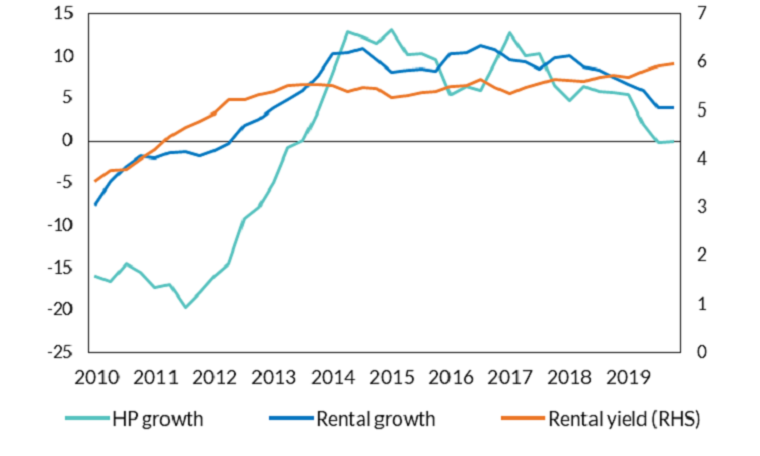

Ireland’s rental market experienced significant shifts after the GFC

Figure 2: Post-crash recovery of the Irish Rental Market (2010–2019)

Source: Daft.ie reports

Note: The growth rates are the annualised growth based on asking prices at Daft.ie. Rental yield is calculated as the ratio of average annual rents to average house prices in a given quarter.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 1.82KB)

Rental yields followed a similar path. Between 2010 and 2012, yields compressed, averaging just 3–4 per cent. From 2013 onward, however, they rose steadily, reaching 6 per cent nationally by the end of 2019. This increase reflected the divergence between more moderate house price growth since 2014 relative to rent inflation, which exceeded 10 per cent annually in many urban centres.

Other housing policies

Several major government policies directly influenced these rental dynamics and must be accounted for in our analysis.

Rent Pressure Zones (RPZs) were introduced at the end of 2016, capping annual rent increases at 4 per cent in designated high-demand areas. By 2019, the number of Local Electoral Areas classified as RPZs had expanded to 27, up from just four at inception (RTB Annual Report, 2021 (PDF 5.3MB)).

The Help-to-Buy (HtB) scheme, launched in January 2017, provided first-time buyers with tax rebates of up to €20,000. Between 2019 and 2023, it supported roughly 30 per cent of first-time buyer mortgages (Bandoni and Singh, 2024 (PDF 526.89KB)). A broad-based assessment (PDF 3.03MB) by the Central Bank find that HtB supports borrowers purchasing larger homes at higher prices.

Furthermore, other concurrent changes to investor taxation, including the expiration of mortgage interest relief in 2017, further discouraged the participation of small landlords.

Since these housing interventions were introduced after 2017, our study focuses on the period between 2012 and 2016, coinciding with the introduction of the measures in Ireland. This approach helps to avoid the empirical difficulty of disentangling overlapping policy effects.

Empirical Approach

Data

This study draws on two core datasets. The first is the Daft.ie House Price and Rent Indices, which provide quarterly hedonic indices for all 26 counties in Ireland, controlling for property characteristics. The second data source is from the Central Bank Loan Level Data (LLD) and Monitoring Template Data (MTD) covering mortgages for primary dwellings in Ireland. These datasets hold rich information on loan characteristics such as loan size, interest rate, LTI and LTV ratios. Additionally, the MTD provides information on borrower characteristics and collateral information. We classify loans by their LTI/LTV limits, collateral counties, and originating banks. We quantify pre-policy exposures by calculating, for each bank in each county, the share of mortgages that would have breached the LTI/LTV limits introduced in 2015.

Empirical design

Our empirical strategy, similar to that of Basten et al. (2021) and Acharya et al. (2022), is designed to isolate the causal effect of the mortgage measures from other concurrent economic factors, such as changes in interest rates. The central challenge is identifying variation in credit supply attributable solely to macroprudential policy. To address this, we construct a county-level index capturing the varying intensity of credit supply changes that could reasonably arise due to the tightening of the measures.

In the first step, we compare the growth of new mortgage lending before and after the reform (using Q4 2014 as the cutoff) across county–bank pairs, explicitly accounting for the pre-existing exposure of each bank in each county to high-LTI/LTV loans. Intuitively, counties more reliant on highly exposed banks should experience a sharper contraction in credit supply after the reform relative to counties less reliant on such banks. We control for county-specific demand factors and time-invariant bank-specific effects using fixed effects.

In the second step, we use the county-level treatment intensity index to estimate the impacts of the measures on county-level housing outcomes (house price growth, rental growth and rental yields). The index functions as an “instrument”, capturing the component of county-level credit supply changes driven exclusively by the measures through banks’ pre-existing exposures. It allows us to assess whether counties predicted—based on their bank composition—to suffer larger credit reductions experienced correspondingly larger changes in housing outcomes.

Key Findings

Rental yield response

The empirical model outlined above yields several findings in the two years following introduction of the measures in 2015.

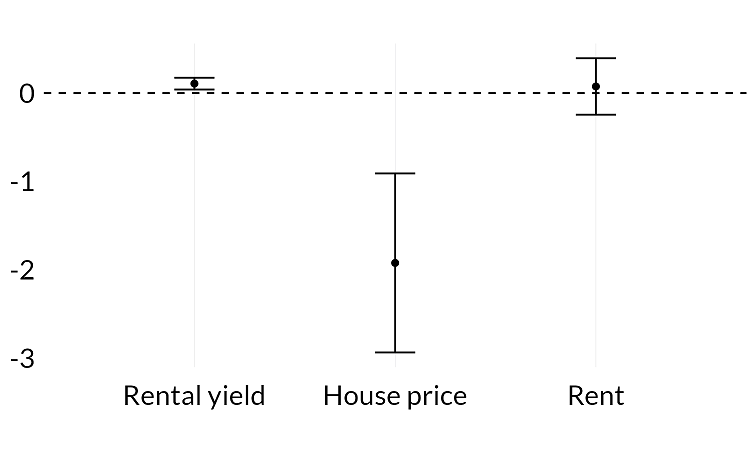

We study the effects from both LTI and LTV on rental yields and find LTV generates statistically insignificant results indicating LTV tightening is less impactful relative to LTI. As for the effect of LTI, the introduction of the LTI cap was associated with a small but statistically significant increase in rental yields (Figure 3). Specifically, a one–standard deviation increase in the treatment intensity index had a significant positive effect on rental yields of 0.09 percentage points. For comparison, the average change in rental yields over the sample period (2012 – 2016) was 0.23 percentage points. Thus, less than 40 per cent of the modest increase in rental yields during this period could be potentially attributed to the introduction of the LTI limit. However, as we discuss below, the effect was driven more by slower house price growth than by rising rents.

House prices and rents

When looking at components of rental yields separately, we find that, following a one–standard deviation increase in the treatment intensity index, there was a strong dampening in the annualised house price growth by 1.9 percentage points, while rental price growth has changed by just 0.07 percentage points (Figure 3). During the sample period, average house prices rose by about 2 per cent, while rents grew by 6.5 per cent annually. We therefore conclude that the LTI limit could be associated with more pronounced slow-down of house price growth than an acceleration of rental inflation, in line with aggregate trends (Figure 2). Consistent with our findings across Irish counties, Moretti and Riva (2025) find that the adoption of borrower-based measures reduces house price growth in a sample of 17 European countries.

A modest rise in rental yields is driven by slower house price growth, instead of rising rents

Figure 3: Estimated elasticities as result of LTI tightening

Note: Data sample in this regression spans from 2012 to 2016. The standard errors are clustered at the county level. The middle point represents the point estimate of elasticity of outcome variables (house price growth, rental price growth, rental yields to one-standard deviation change in the treatment intensity index. The confidence intervals shown in the figure are at 95%.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.45KB)

Factors behind muted rental response

As noted in the theoretical literature, tightening mortgage measures may shift housing demand from owner-occupation to renting, thereby in the absence of a supply response, put upward pressure on rents. This rise in rents, however, might not materialise to the extent expected due to both supply and demand side considerations.

Rental supply

As Kennedy and Stuart (2015) (PDF 337.23KB) argue, rents will not necessarily rise as the supply of rental accommodation may also increase. Higher rental yields attract more institutional investors to expand their investment in the residential rental sector. Cima and Kopecky (2024) (PDF 2.55MB) show that the presence of institutional investors can mitigate upward pressure on rents by boosting supply. Bandoni et al. (2025) (PDF 3.96MB) highlight the significant and growing presence of institutional investors in European housing markets, including Ireland. They find that, in areas with a strong presence of institutional investors, the link between house price growth and local economic fundamentals can weaken. This finding could bear similar implications for Irish rental markets. During our sample period, the influx of institutional investors into the housing market may have contributed to supply in certain rental market segments. However, further work is needed to understand demand/supply balances in the rental market in these years.

Home purchasing behaviour

Besides rental supply factors, responses in housing demand might also play a role. The theoretical argument stresses the importance of shifting demand from owners’ market to rental. In reality, it might not be the case. One of the reasons why the shift to rental might not happen is that buyers find waiting longer will not increase their chance to buy their preferred home in the future, as house prices grow faster than their income. That could lead them to buy either a less ideal home or opt out of the rental market and stay with family to save more. Acharya et al. (2022) show that credit constraints under the mortgage measures reallocate borrowers from urban housing markets to rural counties. International evidence (see e.g. Tzur-Ilan, 2023 and Abreu et al., 2024) also shows that, in the response to a LTV tightening, home buyers near LTV thresholds purchase smaller or lower-quality homes.

Conclusion

This Insight studied the impact of the mortgage measures on local housing markets in Ireland in the two years following introduction in 2015. We find that there are clear and strong effects on house prices, which drive up the rental yield across counties, but find only a small and imprecise direct impact on rents. The muted response of rents might be due to a combination of supply side responses from institutional investors, and demand side responses where credit-constrained home buyers choose not to shift demand to rental markets. Due to data constraints, however, disentangling these effects from the direct impact of the mortgage measures remains challenging. This limitation leaves scope for further research.

References

Abreu, D., Felix, S., Oliveira, V., and Silva, F. (2024). The impact of a macroprudential borrower-based measure on households’ leverage and housing choices. Journal of Housing Economics, 64:101995

Acharya, V., Bergant, K., Crosignani, M., Eisert, T., and McCann, F. (2022). The anatomy of the transmission of macroprudential policies. The Journal of Finance, 77(4):2201–2245

Bandoni E., de Nora, G, Giuzio, M, Ryan, E. and Storz M. (2025), Institutional investors and house prices, ECB Working Paper Series, No 3026., European Central Bank

Bandoni E. and Pratap Singh, A. (2024), Who uses the Help to Buy scheme? Stylised facts and trends, Financial Stability Notes, Vol. 2024, No. 6, Central Bank of Ireland

Basten, C., Briukhova, O. and Pelli, M., (2021), Bank Capital Requirements and Asset Prices: Evidence from the Swiss Real Estate Market. Technical report, University of Zurich

Castellanos, Juan & Hannon, Andrew & Paz-Pardo, Gonzalo, 2025. "How tightening mortgage credit raises rents and increases inequality in the housing market," Research Bulletin, European Central Bank, vol. 127

CENTRAL BANK OF IRELAND, 2014. Macro-Financial Review, 2014: II, Dublin: Central Bank of Ireland

Cima, S. and Kopecky, J., (2024), Housing policy, homeownership, and inequality, Trinity Economics Papers tep0724, Trinity College Dublin, Department of Economics

Greenwald, D. L. and Guren, A. (2021). Do credit conditions move house prices? Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research

Higgins, B. E. (2024). Mortgage borrowing limits and house prices: Evidence from a policy change in ireland. Technical Report 2909, ECB Working Paper

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND, 2014. “Staff Guidance Note on Macroprudential Policy Detailed Guidance on Instruments”, International Monetary Fund, December

Kennedy G. and Stuart, R. (2015), Macro-prudential measures and the housing market, Economic Letter, Vol. 2015, No. 4, Central Bank of Ireland

Moretti

L. and Riva L. (2025), The impact of borrower-based measures: an international comparison, Staff Insight, Vol. 2025, No. 6, Central Bank of Ireland

Residential Tenancies Board, Annual Report 2019

Tzur-Ilan, N. (2023). Adjusting to macroprudential policies: Loan-to-value limits and housing choice. The Review of Financial Studies, 36(10):3999–4044

Endnotes