Key Insights

As flexible, short-term, often interest-free Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) products become increasingly popular, this Insight reveals that individuals displaying certain characteristics of financial vulnerability are using BNPL to a greater extent, more frequently and simultaneously across multiple providers. These characteristics include a history of being refused credit elsewhere, being late on loan repayments previously, exhibiting low financial literacy, and overconfidence.

While BNPL may be a convenient and affordable method to pay for products, our analysis highlights that it is being disproportionately used by those least equipped to manage the risks, raising concerns about debt accumulation.

This underlines the importance of clear disclosures designed with behavioural insights in mind and the implementation of credit checks by providers that take into account total financial commitments by prospective borrowers.

About this Study

Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL)

Imagine you are shopping online and find something that you really want. Paying the full price upfront, however, feels like a stretch for your monthly budget. Now imagine being able to buy the product immediately and pay for it over the next few months, without any interest. This is one of the main appeals of Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL), which facilitates the relaxation of short-term liquidity constraints, offering a broader group of consumers a flexible and seemingly low-cost alternative to traditional credit cards or payday loans. It is typically offered by fintech firms that partner with retailers to provide credit at the point of sale. In recent years, BNPL has seen substantial growth, with Gross Merchandise Value processed through BNPL schemes globally increasing more than sixfold between 2019 and 2023 [Cornelli and Pancotto, 2023]. However, despite its convenience and interest-free structure, BNPL usage is not without risk. Regulators and emerging research have raised concerns about its potential to encourage excessive spending and debt accumulation, while disproportionately affecting financially vulnerable consumers [Di Maggio et al., 2022, CFPB, 2025, Stavins, 2024]. Hence, BNPL occupies a unique position in the consumer credit landscape, warranting close examination of the characteristics of its users.

Study Summary

Using a nationally representative survey from Ireland, we investigate usage patterns of BNPL and examine how consumers’ financial characteristics and behaviours predict both typical and potentially risky patterns of BNPL use, such as frequent usage and engagement with multiple providers at a time. Our findings reveal that BNPL is used to a greater extent, more frequently and across multiple providers at a time, by individuals with characteristics consistent with financial vulnerability [OECD, 2024], including being refused credit elsewhere in the past, being late on loan repayments previously, exhibiting low financial literacy and overconfidence.

Overall, 24% of the survey sample reported using BNPL in the past 12 months. Among those, 30% of users reported using BNPL more than five times and about one third used more than one provider simultaneously. In terms of financial vulnerabilities, individuals with low financial literacy were 22 percentage points more likely to rely heavily on BNPL compared to those with high financial literacy. Consumers who reported being late on repaying loans in the past year were 11 percentage points more likely to use multiple providers at a time compared to those not reporting late loan repayments. In addition, we find that being turned down for credit in the past increases frequent BNPL usage by 15 percentage points and increases the likelihood of using multiple BNPL providers simultaneously by 13 percentage points. This points to BNPL’s role as a fallback or alternative financing tool for consumers with limited access to traditional financial services. In terms of financial characteristics, overconfidence stands out in predicting the likelihood of using multiple BNPL providers at a time. There is a positive and statistically significant effect of 11 percentage points - overconfident individuals may be more inclined to take on multiple BNPL commitments at a time, possibly underestimating the complexity of managing multiple providers.

Contribution

This study contributes to the growing literature on fintech credit and consumer financial behaviour by providing detailed, survey based analyses of BNPL usage and its correlation with indicators of financial behaviour and vulnerability. We move beyond demographic correlates and focus on potential characteristics of vulnerability such as low financial literacy, low self-control, financial distress and loan repayment behaviours as predictors of both standard and potentially risky patterns of BNPL use. By showing that individuals with financial characteristics consistent with vulnerability are significantly more likely to engage in frequent and multi-provider BNPL usage, the paper highlights how fintech-enabled credit may exacerbate pre-existing inequalities in financial wellbeing, in the absence of regulation.

Our findings aim to inform policymakers and regulators as they consider appropriate consumer protections and financial education efforts in response to the rapid growth of BNPL services. While BNPL may be a convenient and affordable method to pay for products, our analysis highlights that it is being disproportionately used by those least equipped to manage the risks, raising concerns about debt accumulation. This underlines the need for ongoing supervision of the BNPL market and provider credit checks that consider pre-existing financial commitments as prescribed in the Irish Consumer Protection Code (PDF 1.63MB). Furthermore, improved consumer disclosures designed with behavioural insights in mind, such as clear, concise reminders of repayment obligations, can help consumers reflect more accurately on their financial capacity, especially those with low financial literacy or with behavioural biases such as overconfidence or inattention. Results from a study conducted by the Behavioural Consumer Finance Unit of the Central Bank of Ireland (cited in Box 3 of the General Guidance on the Consumer Protection Code (PDF 691.68KB)) show how carefully designed disclosures can be integrated at the point of decision-making, helping consumers make informed choices without adding undue friction to the transaction process.

BNPL Landscape

BNPL is a short-term credit product, typically interest-free, which allows consumers to split their payments into a number of instalments, with a down payment typically due at the point of sale. BNPL products are either offered directly to consumers by BNPL providers before purchase or are offered at the point of sale by the retailer who partners with the BNPL provider. The retailer pays a fee to the BNPL provider which is often higher than that for credit cards and is justified in order to access a wider pool of customers, to transfer the credit risk to the BNPL provider, and to benefit from higher conversion rates of shopping baskets into sales [Cornelli and Pancotto, 2023, Lux and Epps, 2022]. For example, a study with a German retailer finds that sales increase by 20% with BNPL availability [Berg et al., 2023].

Although BNPL services have been available in countries like Sweden and the United States since 2005, global usage accelerated significantly with the rise of online shopping during the COVID-19 pandemic. Today, BNPL is most widely adopted in Australia and Sweden, with high usage rates also seen in the UK, US, Germany, China, and other Nordic countries [Cornelli and Pancotto, 2023].

In a nationally representative survey conducted by the Central Bank of Ireland in June 2023, 15% of consumers reported having used BNPL before [CBI, 2023]. In Ireland, BNPL is offered for both online and in-store purchases by three main providers. Humm entered the market in late 2020, followed by Klarna in 2021 and Revolut in 2022. BNPL offerings differ considerably across providers, particularly in terms of credit limits, instalment structure, interest rates, late fees, and other charges. If instalments are late, BNPL providers charge late fees of somewhere between €3 to €9, although higher fees and charges may be applicable for amounts over €500. As Irish credit providers are not required to conduct checks against the Central Credit Register for loans under €500, BNPL providers offering credit below €500 rely on soft credit checks based on internal repayment data or access to customers’ bank accounts and personal information. While access to further BNPL credit is often restricted if a repayment is missed, financially overstretched consumers may still obtain credit from a different BNPL provider. In cases of default, additional charges such as debt collection fees may apply, and the outstanding debt can be passed on to a third-party collection agency.

BNPL was initially unregulated but many countries have introduced (e.g. Australia, US, Sweden), or are moving towards, regulation (UK 2025/26, EU 2026+). In Ireland, BNPL became subject to regulation in May 2022, with a number of provisions from the Consumer Protection Code becoming applicable, mainly relating to creditworthiness assessments and advertising. The Central Bank also completed a review of the terms and conditions of the largest BNPL firms in 2023 and engaged directly with the firms involved to make the terms and conditions clearer for customers. The revised Consumer Protection Code 2025 further extends the provisions applicable for BNPL providers in Ireland.

Potential Benefits and Risks

BNPL offers financial benefits to consumers through short-term, no-interest credit, along with operational advantages such as easily accessible credit and a simple, automatic repayment process. It can be a more cost-effective way to finance purchases compared to traditional loans or credit cards. For instance, as of March 2025, annual percentage rates (APRs) on outstanding personal loans of up to one-year and overdrafts in Ireland were around 11%, while credit card APRs vary between 13.8% and 22.9%. Additional fees also apply, including late payment charges of around €7 for credit cards issued by the three main retail banks. Data from the United States show that consumers are increasingly shifting from credit cards to BNPL products for making payments [Di Maggio et al., 2022]. Similarly, Irish survey data show that 60% of BNPL users or potential users perceive BNPL as more affordable than credit cards [CBI, 2023]. BNPL can also serve as a more affordable alternative to unregulated or high-cost moneylenders, particularly for consumers who might otherwise resort to such sources when faced with short-term credit needs, with 68% reporting BNPL to be more affordable than loans from a money lender [CBI, 2023].

However, research indicates that some BNPL transactions are funded through credit cards, raising concerns about the risk of over-indebtedness and loan stacking among BNPL users [Guttman-Kenney et al., 2023, ASIC, 2020]. As with many financial decisions, behavioural biases also play a role in consumers’ use of BNPL services [Byrne et al., 2022]. The deferral of payment in BNPL arrangements can exploit present-biased preferences—where individuals favour immediate rewards over future outcomes—resulting in a higher willingness to spend [Feinberg, 1986, Prelec and Simester, 2001, Meier and Sprenger, 2010, Werthschulte and Löschel, 2021]. Visual salience can also influence consumer decision-making. When BNPL providers highlight only the benefits of their services, consumers may be encouraged to make unnecessary purchases or take on more credit than they can afford to repay [Hannah Poll, 2021]. Research also shows that low financial literacy can lead to an underestimation of the risks associated with BNPL, further heightening the potential for financial harm [Gerrans et al., 2022].

BNPL Usage Patterns

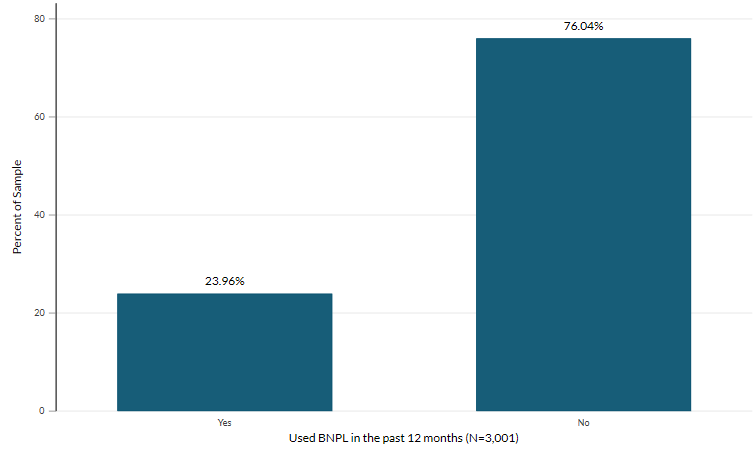

Using data from a nationally representative survey of 3,001 Irish residents, conducted by the Central Bank of Ireland in January 2024, we find that almost 24% of the 3,001 respondents reported using BNPL in the past year (Figure 1).

24% used BNPL in the past year

Figure 1: BNPL use in the past 12 month (as of January 2024)

Source: Authors’ calculation

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (XLSX 12.22KB)

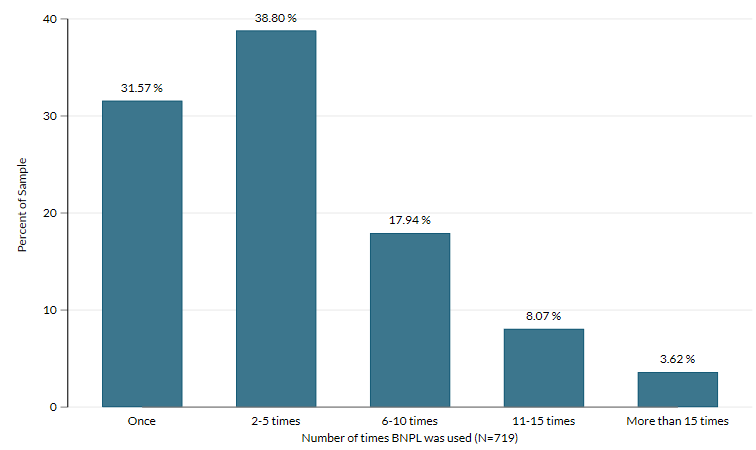

Among these 719 BNPL users, about 68% reported using BNPL more than once, and notably, approximately 30% indicated using BNPL more than five times, while 12% reported using it more than 10 times within the same period (Figure 2).

30% of those who used BNPL in the past year reported using BNPL more than five times

Figure 2 : Number of times BNPL was used in the past 12 months (as of January 2024)

Source: Authors' calculation

Note: Numbers based on those who used BNPL in the past 12 months

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (XLSX 14.23KB)

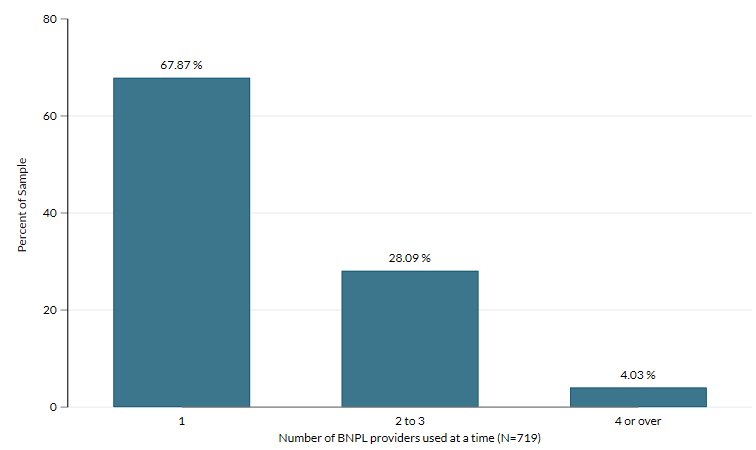

Additionally, a third of those who used BNPL in the past year reported using more than one BNPL provider at the same time (Figure 3). Frequent reliance on BNPL, especially across multiple platforms, may increase the risk of debt accumulation and make it more difficult for consumers to keep track of their financial obligations.

A third of those who used BNPL in the past year reported using more than one BNPL provider at the same time

Figure 3: Number of BNPL providers used at a time (as of January 2024)

Source: Authors' calculation

Note: Numbers based on those who used BNPL in the past 12 months

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (XLSX 14.12KB)

We examine the variation in BNPL usage patterns across key demographic characteristics (Table 1). While the average BNPL usage rate in the sample is 24%, it rises to 31% among individuals aged 18 to 24. Usage then declines sharply with age, dropping to 17% for the 55–64 age group and just 8% for those aged 65 and older. This pattern would be consistent with higher savings and net wealth among older households, which might lead to less reliance on short-term credit (Boyd et al., 2025). Gender differences are also evident, with 25% of women reporting BNPL usage compared to 22% of men. Additionally, BNPL use is more prevalent among individuals with below a third-level education, as well as among employed respondents, compared to unemployed individuals. When analysed by income bands, BNPL usage is relatively consistent, ranging from 23% to 27%, suggesting that BNPL is a short-term credit product used by individuals across a broad income spectrum.

BNPL usage varies across demographic characteristics

Table 1: Average BNPL use in the past year by demographic characteristics (as of January 2024)

| Demographic Characteristics | BNPL use in the past year | BNPL use of more than 5 times | Usage of multiple BNPL providers at a time |

|---|

| Average in Sample | 24% | 30% | 32% |

| Age |

| 18-24 | 31% | 39% | 41% |

| 25-34 | 30% | 40% | 42% |

| 35-44 | 28% | 30% | 36% |

| 45-54 | 25% | 22% | 24% |

| 55-64 | 17% | 20% | 17% |

| 65+ | 8% | 20% | 13% |

| Gender |

| Female | 25% | 32% | 35% |

| Male | 22% | 27% | 28% |

| Other | 9% | 0% | 0% |

| Education |

| Below third-level education | 27% | 29% | 32% |

| Third-level education | 22% | 30% | 32% |

| Employment Status |

| Not employed | 17% | 30% | 27% |

| Employed | 27% | 30% | 33% |

| Income Bands |

| Less than 30k | 23% | 27% | 32% |

| Between 30k and 60k | 27% | 33% | 31% |

| Between 60k and 100k | 23% | 32% | 37% |

| More than 100k | 25% | 11% | 21% |

Source: Authors' calculation

Note: This table shows BNPL use, BNPL use of more than 5 times and use of multiple BNPL providers in the past year across demographic characteristics. For example, 31% of 18-24 year olds used BNPL in the past year compared to 8% of those aged 65 and above. Among those who used BNPL in the past 12 months, 39% of 18-24 year olds reported using it more than 5 times, compared to 20% of those aged 65 and above.

We also explore patterns of BNPL use consistent with riskier behaviour, specifically using BNPL more than five times in a year and using multiple BNPL providers simultaneously. These behaviours are particularly pronounced among younger adults aged 18 to 34. While 30% of BNPL users on average reported using BNPL more than five times in the past year, this share increases to approximately 40% among respondents aged 18 to 34.

Similarly, although 32% of BNPL users reported using more than one provider at a time, this figure rises to 41–42% among those aged 18 to 34. Gender based differences are also notable: 32% of female BNPL users reported using the service more than five times compared to 27% of male users, and 35% of women used multiple providers compared to 28% of men. These patterns are not concentrated among respondents in the lowest annual income group (under €30,000), and for instance, among those using multiple providers usage is highest in the €60,000 - €100,000 group. This suggests that, rather than income, financial behaviours may be associated with BNPL usage.

Predicted BNPL Usage Based on Financial Vulnerabilities

Methodology

In this section, we use regression analysis to examine how various indicators of financial and borrowing behaviour predict the likelihood of BNPL usage. Specifically, we estimate how these characteristics determine three distinct BNPL usage patterns: (1) whether an individual used BNPL in the past year, (2) whether they used BNPL more than five times in that period, and (3) whether they engaged with multiple BNPL providers simultaneously, where (2) and (3) act as proxies for potentially risky usage as discussed earlier. To do this, we employ a logit regression model and report average marginal effects, which represent the predicted change in the likelihood of each outcome associated with the relevant behavioural trait, controlling for the influence of other variables included in the model. All regressions include a set of demographic controls selected through a double LASSO procedure, an approach that systematically identifies statistically relevant covariates for predicting the dependent variable.

We rely on self-reported measures of financial vulnerabilities related to day-to-day financial and borrowing behaviours. In relation to self-assessment of day-to-day financial behaviours such as self-control, financial distress and financial self-efficacy, even though these are subjective measures, they are found to be valuable proxies for real-life financial behaviour, capturing important dimensions of financial well-being that objective indicators such as income or debt balances often miss (Netemeyer et al., 2018). For example, Lusardi and Tufano (2015) demonstrate that self-assessed financial literacy is correlated with actual financial knowledge and the quality of financial decision-making (Lusardi& Tufano , 2015. The loan behaviour-related variables, such as being late on repayments, are susceptible to social desirability bias, meaning respondents may underreport negative or risky behaviours to present themselves in a more favourable light (Tourangeau & Yan, 2007). However, such underreporting bias suggests that any positive relationship observed between poor borrowing history and BNPL use is likely a conservative estimate, and, if anything, the true association may be even stronger than the data indicate. Because these self-reported measures often align with and help explain real behaviours, they are widely used in household finance research and policy design when comprehensive administrative data is unavailable (OECD, 2013).

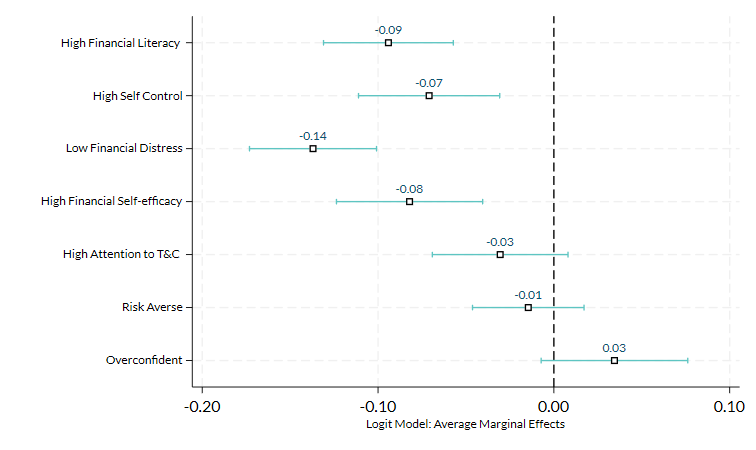

Predicted Usage By Day-to-day Financial Behaviours

We find that low financial distress is associated with a 14-percentage point decrease in the likelihood of BNPL use in the past year, controlling for other financial and demographic characteristics (Figure 4). Similarly, more than a median level of financial literacy, self-control (which we use as a proxy for present-biased behaviour) and financial self-efficacy each reduce the likelihood of BNPL usage by 7–9 percentage points. Other behavioural traits such as attention, risk preferences and overconfidence are not significantly linked to having used BNPL in the past 12 months. This suggests that individuals who are more financially informed, disciplined, and confident in managing their finances are less likely to turn to BNPL.

Individuals who are more financially informed, disciplined, and confident in managing their finances less likely to turn to BNPL

Figure 4: Prediction of BNPL Usage by Day-to-day Financial Behaviours

Source: Authors' calculation

Note: The figure reports marginal effect estimates from a logit model, where the dependent variable takes the value of 1 if the individual reports using BNPL in the past year (as of January 2024). The dependent variable is regressed on a number of financial behaviours, with the demographic controls for each logit model selected using a double lasso procedure. All variables used are binary and point estimates are expressed in percentage points. For instance, individuals with high financial literacy are 9 percentage points less likely to have used BNPL in the past year compared to those with low financial literacy, after controlling for all other variables in the model.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (XLSX 12.64KB)

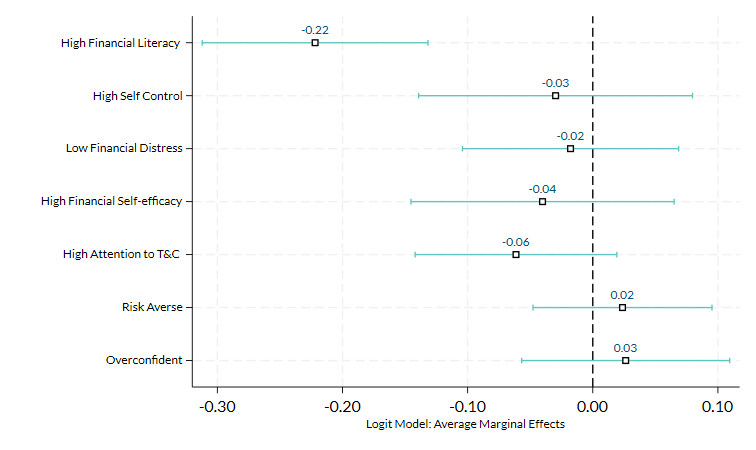

Focussing on the likelihood of using BNPL more than five times, high financial literacy shows a strong negative effect, decreasing the probability of frequent BNPL use by 22 percentage points, suggesting that individuals with more than a median level of financial literacy are less likely to rely heavily on BNPL (Figure 5).

Individuals with high financial literacy less likely to rely heavily on BNPL

Figure 5: Prediction of BNPL Usage More than Five Times by Day-to-day Financial Behaviours

Source: Authors' calculation

Note: The figure reports marginal effect estimates from a logit model, where the dependent variable takes the value of 1 if the individual reports using BNPL more than 5 times in the past year (as of January 2024). The dependent variable is regressed on a number of financial behaviours, with the demographic controls for each logit model selected using a double lasso procedure. All variables used are binary and point estimates are expressed in percentage points. For instance, individuals with high financial literacy are 22 percentage points less likely to have used BNPL more than five times in the past year compared to those with low financial literacy, after controlling for all other variables in the model.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (XLSX 12.53KB)

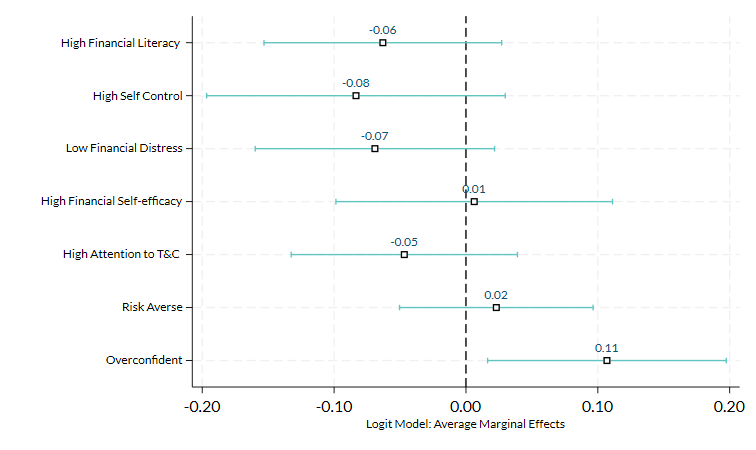

Overconfidence as a behavioural trait stands out in predicting the likelihood of using multiple BNPL providers at a time, with a positive and statistically significant effect of 11 percentage points, implying that overconfident individuals may be more inclined to take on multiple BNPL commitments at a time, possibly underestimating the complexity or risk of managing multiple providers (Figure 6). While low financial distress is negatively associated with frequent and multi-provider BNPL usage it is not statistically significant.

Overconfident individuals more inclined to take on multiple BNPL commitments at a time

Figure 6: Prediction of Using More than One Provider at a time by Day-to-day Financial Behaviours

Source: Authors' calculation

Note: The figure reports marginal effect estimates from a logit model, where the dependent variable takes the value of 1 if the individual reports using more than one provider at a time in the past year (as of January 2024). The dependent variable is regressed on a number of financial behaviours, with the demographic controls for each logit model selected using a double lasso procedure. All variables used are binary and point estimates are expressed in percentage points. For instance, individuals who are overconfident are 11 percentage points more likely to have used multiple BNPL providers at a time in the past year compared to those with no overconfidence, after controlling for all other variables in the model.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (XLSX 12.55KB)

Predicted Usage By Borrowing Behaviours

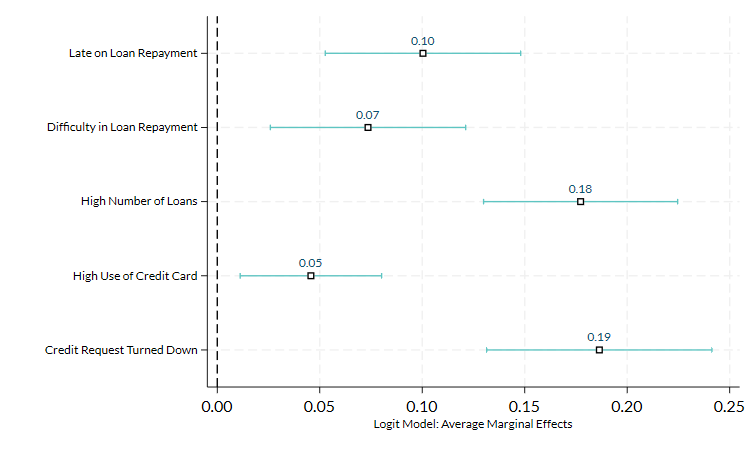

This section analyses how previous borrowing behaviour — such as late payments, repayment difficulties, high loan or credit card usage, and credit denials — predict the likelihood of BNPL usage, frequent usage, and use of multiple providers simultaneously . We find that all indicators of financial vulnerability related to past borrowing behaviour significantly predict BNPL usage over the past 12 months (Figure 7). The most influential factors for using BNPL in the past year are having an above median number of loans and being denied credit from other sources, by 18 and 19 percentage points, respectively. Being late on a loan repayment and having experienced difficulty in making a loan repayment in the past year are associated with increases in BNPL use of 10 and 7 percentage points, respectively. Above median usage of credit cards also increases BNPL usage in the past year by 5 percentage points.

All indicators of financial vulnerability related to past borrowing behaviour significantly predict BNPL usage over the past 12 months

Figure 7: Prediction of BNPL Usage by Borrowing Behaviours

Source: Authors' calculation

Note: The figure reports marginal effect estimates from a logit model, where the dependent variable takes the value of 1 if the individual reports using BNPL in the past year (as of January 2024). These dependent variables are regressed on a number of borrower behaviours, with the demographic controls for each logit model selected using a double lasso procedure. All variables used are binary and point estimates are expressed in percentage points. For instance, individuals who had a credit request turned down within the last year were 19 percentage points more likely to have used BNPL compared to those who were not turned down for credit, after controlling for all other variables in the model.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (XLSX 12.54KB)

Focusing on borrowers who used BNPL more than five times, being turned down for credit previously increases frequent usage by 15 percentage points relative to those who have not been turned down for credit (Figure 8).

Being turned down for credit previously increases frequent BNPL usage

Figure 8: Being turned down for credit previously predicts frequent BNPL usage

Source: Authors' calculation

Note: The figure reports marginal effect estimates from a logit model, where the dependent variable takes the value of 1 if the individual reports using BNPL for than five times in the past year (as of January 2024). These dependent variables are regressed on a number of borrower behaviours, with the demographic controls for each logit model selected using a double lasso procedure. All variables used are binary and point estimates are expressed in percentage points. For instance, individuals who had a credit request turned down within the last year were 15 percentage points more likely to have used BNPL more than 5 times compared to those who were not turned down for credit, after controlling for all other variables in the model.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (XLSX 12.45KB)

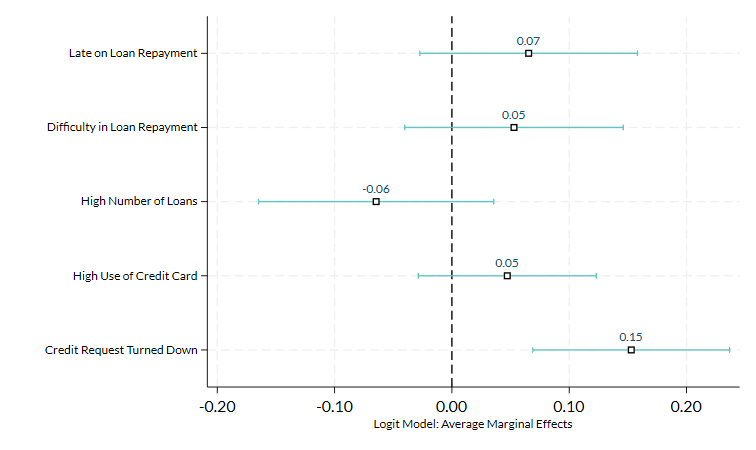

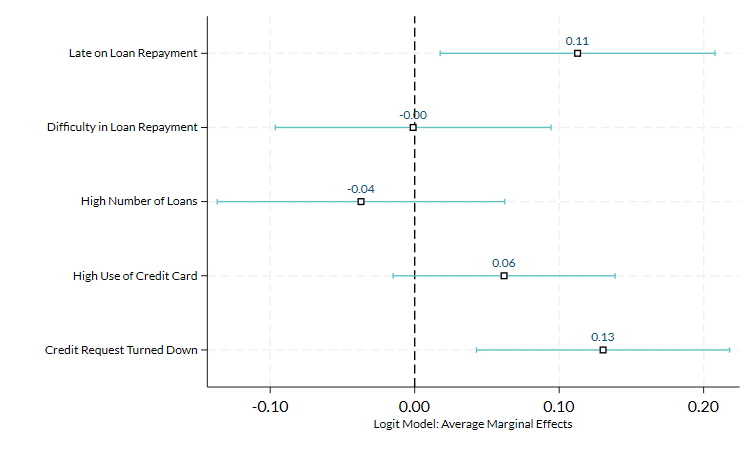

Finally, examining usage of multiple BNPL providers at a time, we find that having previously been late on loan repayments increases the likelihood of using multiple providers at a time by 11 percentage points (Figure 9). Being turned down for credit also increases the likelihood of using multiple BNPL providers simultaneously by 13 percentage points. This highlights BNPL’s role as a fallback or alternative financing tool for consumers with limited access to traditional financial services.

Being late on loan repayments or turned down for credit previously increases multiple provider usage

Figure 9: Being late on loan repayments or turned down for credit previously predicts higher multiple provider usages

Source: Authors' calculation

Note: The figure reports marginal effect estimates from a logit model, where the dependent variable takes the value of 1 if the individual reports using more than one BNPL provider at a time in the past year (as of January 2024). These dependent variables are regressed on a number of borrower behaviours, with the demographic controls for each logit model selected using a double lasso procedure. All variables used are binary and point estimates are expressed in percentage points. For instance, individuals who had a credit request turned down within the last year were 13 percentage points more likely to have used more than one provider at a time compared to those who were not turned down for credit, after controlling for all other variables in the model.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (XLSX 12.46KB)

Conclusion

This paper presents new evidence on the usage patterns of BNPL in Ireland and finds that BNPL usage is disproportionately concentrated among individuals exhibiting markers of financial vulnerability. Frequent usage and the use of multiple BNPL providers, which we use as a proxy for risky BNPL behaviour, are especially prevalent among those with low financial literacy and overconfidence. In addition, individuals who have been denied credit and have a history of being late on loans are also more likely to engage in risky BNPL usage patterns.

While we cannot establish causality in this study on whether financially vulnerable individuals engage in risky patterns of BNPL usage or whether engaging in risky BNPL practices contributes to their vulnerability, our findings raise important concerns about the risks of overextension associated with BNPL usage, particularly as BNPL becomes increasingly integrated into everyday consumer spending. The behavioural ease and low friction access offered by BNPL may obscure the true cost of borrowing for financially vulnerable consumers. The results point to the importance of regulation for this sector and the implementation of credit checks by providers that take into account total financial commitments by prospective borrowers. The Central Bank’s Guidance on Protecting Consumers in Vulnerable Circumstances, together with the revised Consumer Protection Code 2025 requirements, represent important safeguards in this context.

Beyond regulation and supervision, enhancing financial literacy is crucial to support informed consumer decision making. The Central Bank’s contribution to the Financial Literacy Executive Board, in collaboration with other stakeholders, on the development and implementation of the National Strategy for Financial Literacy, and its targeted media campaigns and consumer Hub to educate and inform consumers of the associated risks supports this objective (Consumer Hub). In addition, behaviourally informed disclosures addressing over- confidence and inattention can help consumers make more informed borrowing decisions (Box 3, General Guidance on the Consumer Protection Code (PDF 691.68KB)). More broadly, further research into the behavioural drivers of BNPL use can inform the design of fintech credit products that enhance, rather than undermine, consumer financial wellbeing.

References

ASIC. Buy now pay later: An industry update. Technical report, Australian Securities and Investments Commission, 2020.

T. Berg, V. Burg, J. Keil, and M. Puri. On the rise of ’buy now, pay later’. Pay Later’ (May 15, 2023), 2023.

L. Boyd, S. Byrne, and T. McIndoe Calder. The evolution of household savings: determinants and implications. Quarterly Bulletin Articles, pages 2–37, 2025.

S. Byrne, K. Devine, and Y. McCarthy. Behavioural economics and public policy-making. Quarterly Bulletin Articles, pages 85–103, 2022.

CBI. Buy now pay later - consumer insights update. Technical report, Central Bank of Ireland, 2023.

CFPB. Consumer use of buy now, pay later and other unsecured debt. Technical report, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2025.

G. L. Cornelli, G. and L. Pancotto. Buy now, pay later: a cross-country analysis. 2023.

M. Di Maggio, E. Williams, and J. Katz. Buy now, pay later credit: User characteristics and effects on spending patterns. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022.

T. Dohmen, A. Falk, D. Huffman, U. Sunde, J. Schupp, and G. G. Wagner. Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3):522–550, 2011.

R. A. Feinberg. Credit cards as spending facilitating stimuli: A conditioning interpretation. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(3), 348–356, 1986.

E. Gaffney and P. Lyons. An overview of the consumer credit market in Ireland. 2024.

P. Gerrans, D. G. Baur, and S. Lavagna-Slater. Fintech and responsibility: Buy-now-pay-later arrangements. Australian Journal of Management, 47(3):474–502, 2022.

B. Guttman-Kenney, C. Firth, and J. Gathergood. Buy now, pay later (bnpl)... on your credit card. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 37:100788, 2023.

G. B. Hannah Poll. Buy now...pain later? Technical report, UK Citizens Advice, 2021.

J. M. Lown. Development and validation of a financial self-efficacy scale. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 22(2):54, 2011.

A. Lusardi and O. S. Mitchell. The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. American Economic Journal: Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1):5–44, 2014.

A. Lusardi and P. Tufano. Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. Journal of pension economics & finance, 14(4):332–368, 2015.

M. Lux and B. Epps. Grow now, regulate later? regulation urgently needed to support transparency and sustainable growth for buy-now, pay-later. 2022.

S. Meier and C. Sprenger. Present-biased preferences and credit card borrowing. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(1):193–210, 2010.

Money and Pensions Service. (2018). UK Financial Capability Survey 2018. London: Money and Pensions Service.

R. G. Netemeyer, D. Warmath, D. Fernandes, and J. G. Lynch. How am i doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(1):68–89, 2018.

OECD. OECD guidelines on measuring subjective well-being. Technical report, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264191655-en, 2013.

OECD. Financial consumer protection in Ireland: A review of the Central Bank of Ireland’s supervisory functions. Technical report, https://doi.org/10.1787/5315c3ca-en, 2024.

D. Prelec and D. Simester. Always leave home without it: A further investigation of the credit-card effect on willingness to pay. Marketing letters, 12:5–12, 2001.

J. J. Ray and J. M. Najman. The generalizability of deferment of gratification. The Journal of Social Psychology, 126(1), 117–119, 1986.

J. Stavins. Buy now, pay later: Who uses it and why. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Research Paper Series Current Policy Perspectives Paper, (2024-3), 2024.

R. Tourangeau and T. Yan. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological bulletin, 133(5):859, 2007.

M. Werthschulte and A. Löschel. On the role of present bias and biased price beliefs in household energy consumption. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 109: 102500, 2021.

Appendix

Table 1: Definitions of variables used

| Variable | Definition |

|---|

| High Financial Literacy (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014) | Dummy variable equal to one if the number of correct answers provided by the respondent to the three questions below measuring financial literacy is above the median respondent, and zero otherwise.

1. Imagine that the interest rate on your savings account was 1% per year and inflation was 2% per year. After 1 year, how much would you be able to buy with the money in this account?

· More than today

· Exactly the same

· Less than today

· I don’t know

2. Imagine that someone puts €100 into a no fee, tax-free savings account with a guaranteed interest rate of 2% per year. They don’t make any further payments into this account and they don’t withdraw any money. How much would be in the account at the end of the first year, once the interest payment is made? Enter -99 (minus 99) if "Don't Know".

3. It is usually possible to reduce the risk of investing in the stock market by buying a wide range of stocks and shares?

· Yes

· No

· Don’t Know

|

| High Self Control (Ray and Najman, 1986)_ | Dummy variable equal to one if respondent’s score to three questions related to financial habits (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree) is below the median respondent score, and zero otherwise.

· It is hard for me to resist buying things I cannot afford.

· When someone gives me money, I prefer to spend it right away.

· I manage my money well.

|

| Low Financial Distress (UK Financial Capability Survey, 2018) | Dummy variable equal to one if respondent’s score to three questions related to financial distress is below the median respondent score and, zero otherwise:

1. Thinking about any consumer debts you have, to what extent is keeping up with the repayment of them and any interest payments a financial burden? Would you say it was:

· A heavy burden.

· Somewhat of a burden.

· Not a problem at all.

· I have no consumer debts.

2. Which one of the following statements best describes how well you are keeping up with your bills and credit commitments at the moment?

· Having real financial problems and have fallen behind with many of them.

· Falling behind with some of them.

· Keeping up with all of them, but it is a constant struggle.

· Keeping up with all of them, but it is a struggle from time to time.

· Keeping up with all of them without any difficulties

· Don’t have any commitments.

3. In the past 12 months, how often have you run out of money before the end of the week or month and needed to use a credit card or overdraft to get by?

· Always

· Most of the time

· Sometimes

· Hardly ever

· Never |

| High Financial Self-efficacy (Lown, 2011) | Dummy variable equal to one if respondent’s score in relation to agreement to three questions related to financial self-efficacy (totally true to totally false) is below the median respondent score and, zero otherwise:

1. It is hard to stick to my spending plan when unexpected expenses arise.

2. When unexpected expenses occur, I usually have to use credit.

3. I lack confidence in my ability to manage my finances.

|

| High Attention to T&C (adapted from Financial Capabilities Survey 2017, UK FCA) | Dummy variable equal to one if respondent read the terms and conditions carefully or briefly while making financial decisions using online services, and zero otherwise |

| Risk Averse (Dohmen et al., 2011) | Dummy variable equal to one if respondent score for risk averse behaviour score ranging from 0 to 5 (low to high) is above the median respondent, and zero otherwise.

Question used for measuring risk averse behaviour score: We would like to know how you would choose between Money For Sure and €100 with a 50% chance of receiving that amount.

Which reward would you prefer?

· €10 For Sure

· €100 with a 50% chance

Which reward would you prefer?

· €20 For Sure

· €100 with a 50% chance

Which reward would you prefer?

· €30 For Sure

· €100 with a 50% chance

Which reward would you prefer?

· €40 For Sure

· €100 with a 50% chance

Which reward would you prefer?

· €50 For Sure

· €100 with a 50% chance

Risk averse score equal to 5 if respondent chooses €10 For Sure, 4 if respondent chooses €20 For Sure, 3 if respondent chooses €30 For Sure, 2 if respondent chooses €40 For Sure, 1 if respondent chooses €50 For Sure, 0 if respondent chooses €100 with a 50% chance always

|

| Overconfident (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014) | Dummy variable equal to one if number of answers respondent thinks they got correct out of the three questions measuring financial literacy is above their actual score out of three, and zero otherwise. |

Late on Loan Repayment (By the authors)

| Dummy variable equal to one if respondent ever made a late repayment for a loan in the past 12 months, and zero otherwise. |

Difficulty in Loan Repayment (By the authors)

| Dummy variable equal to one if respondent ever had difficulty in repaying a loan in the past 12 months, and zero otherwise. |

High Number of Loans (By the authors)

| Dummy variable equal to one if respondent’s current number of loan are above the median respondent, and zero otherwise. |

High Use of Credit Card (By the authors)

| Dummy variable equal to one if respondent’s uses credit card more than 2-3 times a week or more than 2-3 times a month, and zero otherwise. |

| Credit Request Turned Down (By the authors) | Dummy variable equal to one if any lender has turned down credit application by the respondent either completely or for partial amount requested, and zero otherwise. |

Endnotes